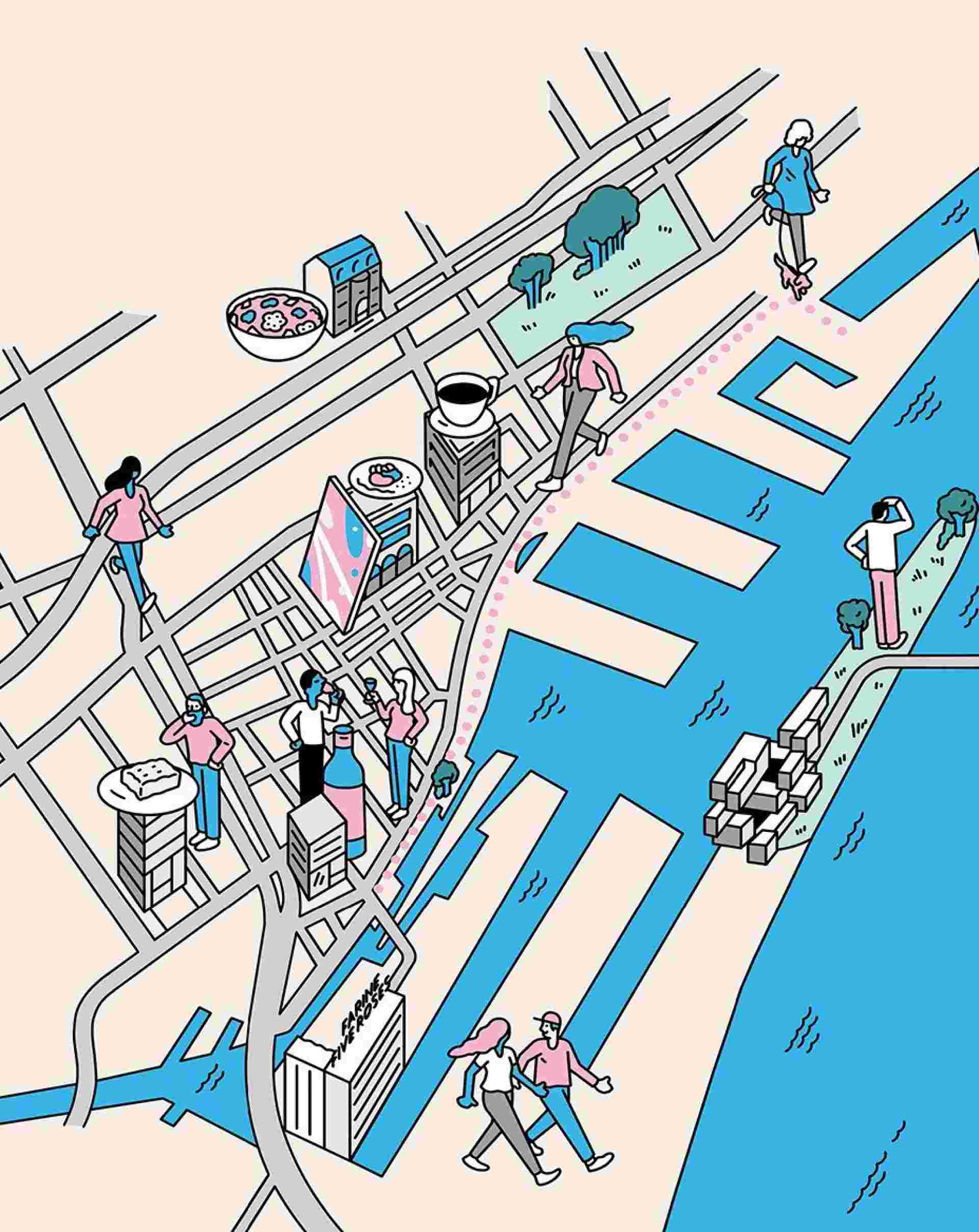

111 Robert- Bourassa

Sights and strolling around Montreal’s Cité Multimédia

BY: Yaniya Lee

PHOTO BY: Alana Paterson

Gina Badger is a kitchen witch, a queer femme, an artist, a settler and an energetic herbalist who believes in the coexistence of all living things—more so, that humans and plants are in constant, reciprocating collaboration. “And that starts with our breathing,” says Badger. “What we exhale is what they inhale, and what they exhale is what we inhale.” For Badger, plants are medicine, but they’re also teachers, informing her values and ways of working. “There’s a real temptation to look for the easy thing that’s going to change us overnight. Herbalism largely confounds that desire,” she says. She called her Vancouver-based practice Long Spell because she believes “the most profound changes happen gradually and slowly, over time.”

Growing up in Alberta, Badger used to go on walks with her grandmother, who taught her about plants in the wild. (Her mother has had a lifelong passion for theatre and is an expressive-arts therapist, and her other grandmother is a painter.) Plants became a major part of Badger’s artistic development. She studied to be an artist at Concordia University in Montreal and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where her media was not canvas, paint, clay or pixels but gardening, cooking, pedagogy and performance. A 2011 project, Mongrels, included a walking tour during which Badger shared the history of mugwort, a weed with medicinal properties. This was followed by Magical Faggots, a collaborative performance in which the performers’ ancestries were explored and the disparaging term was reclaimed through the burning of bundles of branches, sticks and twigs.

She was intent on dissolving the boundary between art and its audience and her practice and person, and herbalism provided her with a sensuous, process-based approach—not exactly anti-intellectual but all-encompassing. “‘Sensuousness’ is an interesting word because sometimes people think of it as being sexual,” says Randy Lee Cutler, a Vancouver artist and friend of Badger’s. “But I think it’s about being engaged in the senses.”

“For years, I was making art with plants in it, but it was often abstracted or theoretical in ways that prevented me from being engaged creatively, intuitively and sensually with the material,”

“We smell them and we taste them, so interacting with plants brings us into our sensory apparatus, into our bodies, and gets us out of our heads, which is the foundation of being grounded and being present,” says Badger. This allows her to then become a conduit between the environment and our bodies, between plants and people. Badger’s sessions with clients begin with a conversation about their health, which guides her in the creation of an herbal formula specific to their needs. “Care comes down to a quality of attention and a quality of presence,” Badger explains. “Lots of herbalists, myself included, get pretty nerdy about when we make our medicines—harvesting at certain times of the moon cycle, for example. That’s really creative, satisfying and connecting—in ways that are reflected in the quality of the medicine.”

ABOVE LEFT: Badger’s library of tinctures, used in her formulas. ABOVE RIGHT: Badger steeps raw plant material in alcohol for two to six weeks to create each tincture, a process called “macerating.”

Badger’s practice is also shaped by strong social and historical awareness. “[Because I’m] a settler with European ancestry practising in what’s now called Canada, acknowledging settler colonialism is a foundational part of my ethics,” she says. “You can’t separate plants from the land, and you can’t separate either of these from Indigenous culture and knowledge.” She studies and works with many teachers (in addition to the training she received at the Blue Otter School of Herbal Medicine, the Compassion Roots Wellness Centre and Emery Herbals) and shapes her practice based on what she has learned. This includes, for instance, her decisions to avoid certain sacred Indigenous plants and to harvest from the wild; instead, she focuses on plants that can easily be cultivated.

Badger in her garden in Vancouver’s Mount Pleasant neighbourhood, where she grows chard, garlic, ornamental perennials, as well as some medicinal plants (though most come from her network of growers).

In energetic herbalism, tiny doses of herbs are taken for their emotional and spiritual properties. ABOVE: Badger adds hawthorn berry (Crataegus spp.) to formulas to widen people’s window of tolerance for challenging emotions, especially grief, and to offer a sense of protection.

Rebecca Cariati, a friend and colleague who practises acupuncture and herbalism, collaborated with Badger to create Wet Coast Mutual Aid Kits, herbal wellness kits (alcohol-free and mostly made up of weedy, widely available garden herbs like rosemary, sage, oregano and lavender) that were distributed to groups especially vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic. Whiteness and settler colonial responsibility were things they acknowledged through the project. “[But] that awareness is not only a mental faculty,” says Cariati. “It’s also something that Gina practises in the way she thinks about which herbs to use and in the way she harvests and sources them. It’s truly woven into her fabric.”

Badger engages with these issues and positions herself within the ongoing legacies of the past in order to imagine and enact change. Her vision of a harmonious society is one centred on restorative justice and creating networks of care. “A model of addressing harm, injury and injustice that is based on an idea of strengthening relationships and on healing rather than punishment—that’s my fantasy,” she says. For clues about what that process could look like, she looks to our generous, nourishing, reciprocal relationship with plants. “They offer us their medicine through visual beauty. They offer us their medicine by asking us—especially in the world we live in now—to really slow down, to be present with them and present with our bodies.”

Steams are super versatile—use them to ward off a respiratory virus, soothe a dry throat during (Vancouver’s) fire season, relieve congestion from allergies, or as a meditative break—and offer a safe and financially accessible way to work with medicinal plants. This method uses herbs that are easy to grow or can be found in the produce or herbal tea section of the supermarket.

NOTE: Herbal steams are generally safe regardless of prescription medications and health conditions. That said, avoid using spicy or strong herbs that could irritate the sensitive tissues of the respiratory tract. If you want to use herbs other than the ones listed here, consult someone with herbal knowledge. For some people, the steam can be irritating and in very rare cases could trigger an asthmatic reaction, so pay attention and don’t do anything that feels wrong in your body.