Kellen Hatanaka

Fill In The Blank Kellen Hatanaka’s urban infill.

By Ximena González

Photos Courtesy of Unbuilders

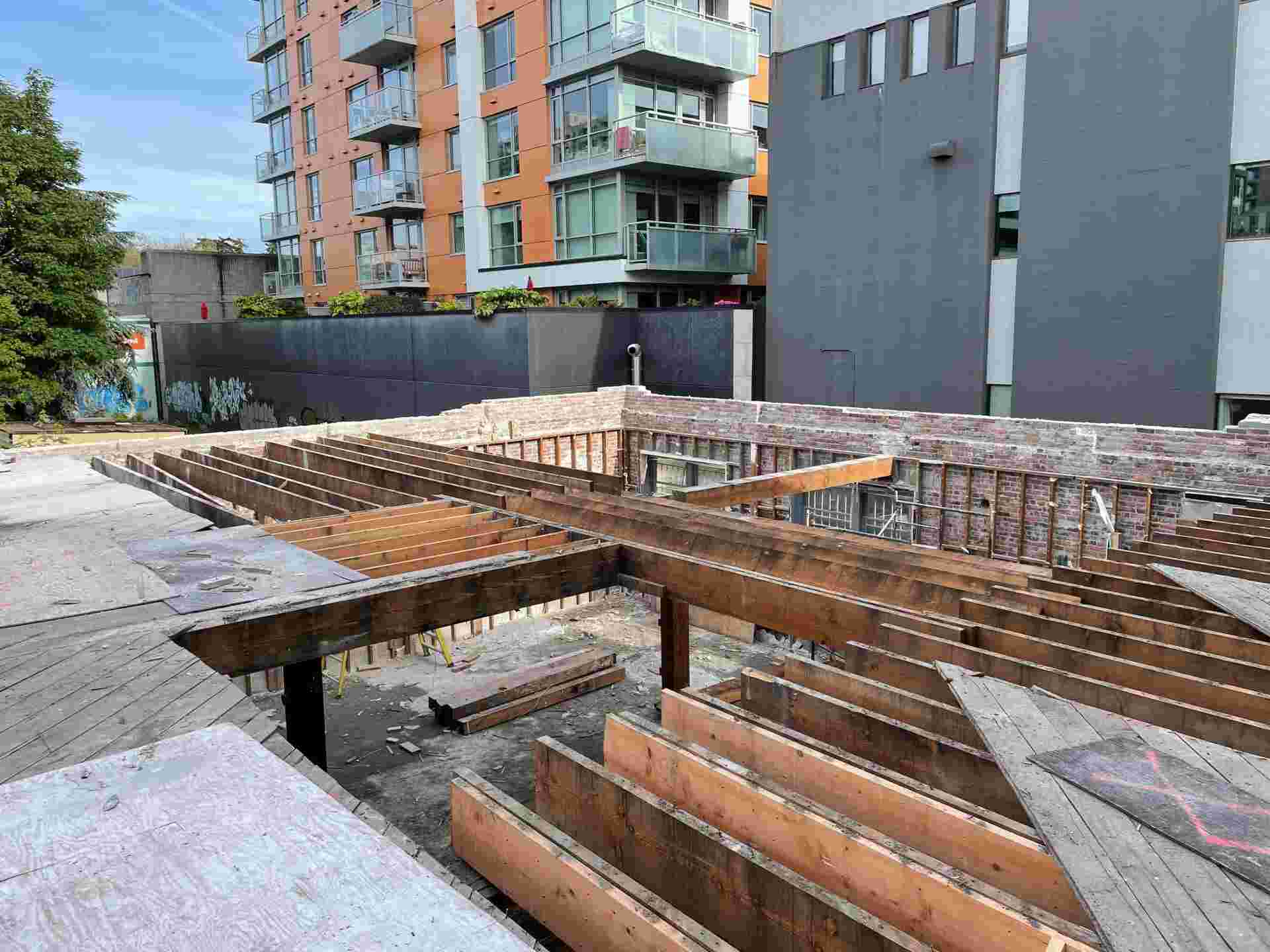

Layer by layer, over the course of six months, the Unbuilders crew deconstructed three buildings in downtown Victoria. Non-structural elements were removed and disposed of, while wood flooring and windows were salvaged.

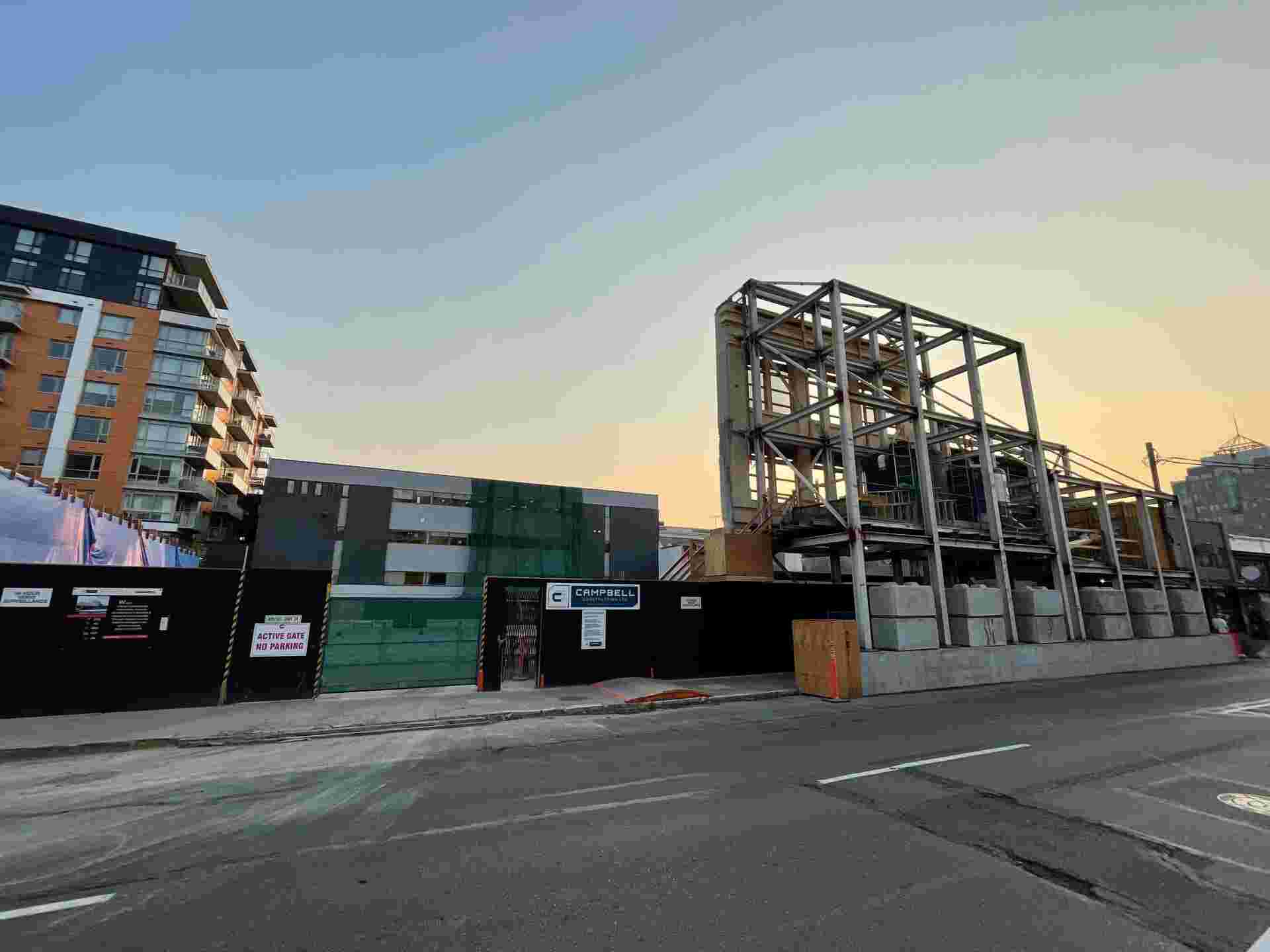

In the summer of 2022, three heritage buildings in downtown Victoria were decommissioned in an unusual fashion. Using a reverse construction system, Adam Corneil and his crew at Unbuilders diverted more than 300,000 board feet of lumber from the landfill, making room for a development while offsetting a portion of the carbon footprint that a brand-new building represents.

Based in Vancouver, Corneil’s company has been deconstructing buildings across British Columbia to sell or donate materials that would otherwise be destined for the landfill since 2018 as his vision for a more sustainable future comes to fruition. “The entire point of [deconstructing] is maximizing salvage value and minimizing waste,” he says. “and doing so in a time-effective and cost-effective manner.”

In Canada, demolition accounts for 12 percent of all solid waste generated. But not everything that ends up in the landfill should. “There’s not a single project that has no salvage value,” Corneil says, noting that sinks, cabinets, windows and flooring can often get a second life.

Usually, demolition companies salvage big timber from commercial jobs, but given the fast-paced nature of their work, Corneil explains, they only scratch the surface. “If we take the same building and our crew [demolishes] it … they’re getting 5 to 10 percent of what our crew gets.”

When the Salient Group, an award-winning developer, proposed the idea of “unbuilding” three heritage structures on Fort Street, Corneil jumped at the opportunity. “All three buildings were built very differently,” he says. “It was interesting for our team.”

After an initial evaluation of each building’s components, the crew identified areas that had toxic materials, like asbestos and lead, in need of removal. “There were some really odd things in these buildings,” says Corneil. “The middle building was four storeys with concrete walls on the sides and brick on the front and back, and they’d used some sort of asbestos tar that had dripped down the concrete for four storeys.”

This unlikely discovery led to some initial “hiccups” that Unbuilders quickly addressed, but a month later, the workers were back on track and ready to begin the initially planned salvage.

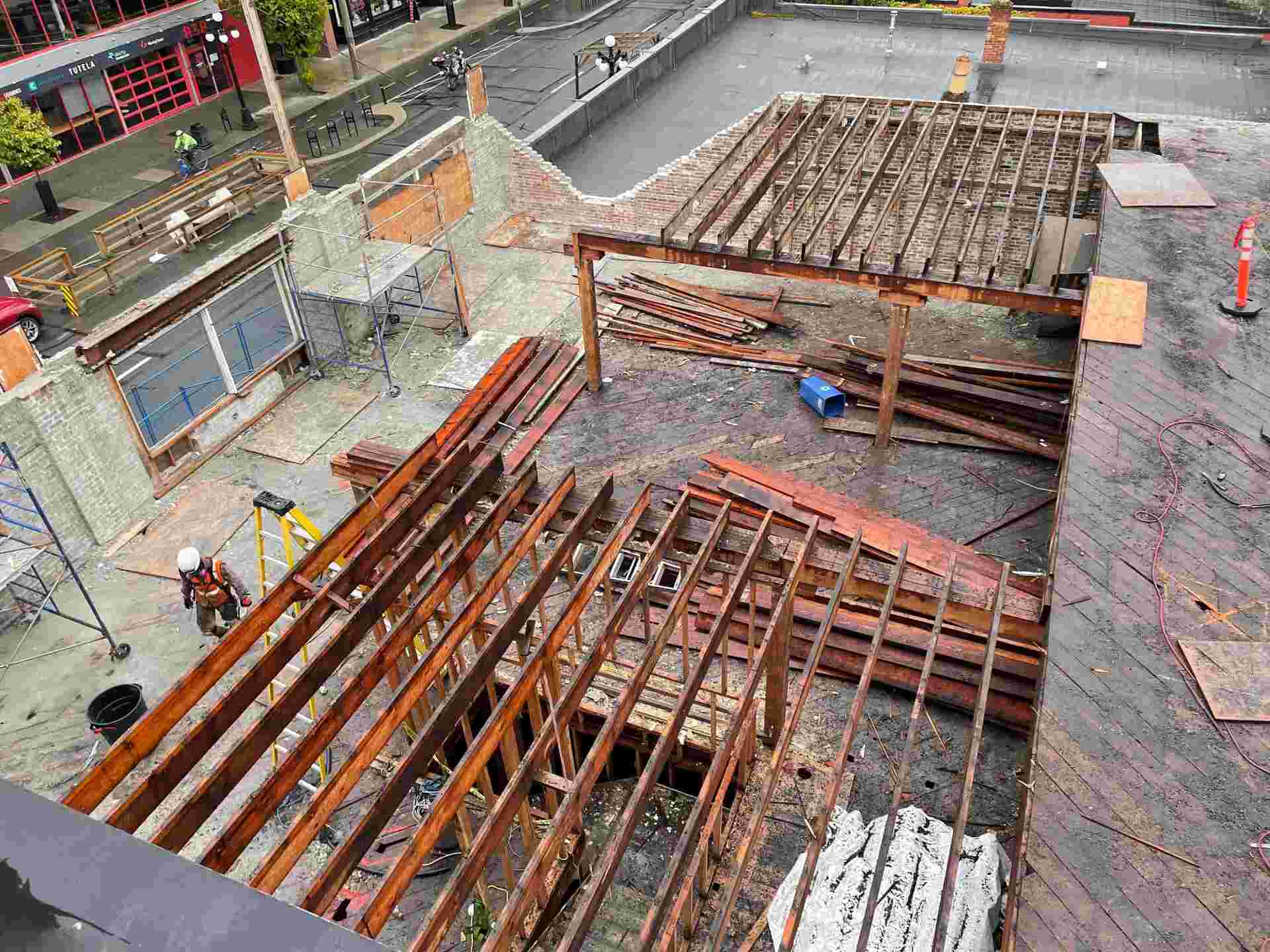

Deconstructed in two stages, the buildings were first stripped of drywall, utilities and flooring. Afterward, crews dismantled structural elements such as roofing, columns and beams. But this was not a simple process.

“It was extremely complex. Engineering was involved,” says Corneil. “The side buildings, built in 1908, were wood-floor structures with brick all around, so a lot of the brick [had to be] taken down by hand.”

Furthermore, because the Edwardian facades of two of the buildings had to be preserved and the salvage process would take place in tandem with the demolition of structural concrete walls, Corneil and his crew had to find a way to maintain the building’s structural integrity while dismantling it.

The advantages of salvaging old-growth lumber go beyond environmental factors as it is stronger and denser than standard lumber.

The most complex part of the demolition project was deconstructing the middle building because the side walls had to be remediated prior to demolition and the historical facade of an adjacent building preserved.

Brick walls were deconstructed by hand using a process that ensured that the integrity of the bricks would be maintained so they could be reused. Damaged bricks were recycled.

Unbuilders salvages dimensional lumber, shiplap, large posts and beams as well as plank flooring and sells these materials locally. In this project alone, 300,000 board feet of lumber were diverted from the landfill.

“We braced the entire building, almost like [when] you’re pouring concrete,” Corneil describes. Once the exterior structure was secured, a mini-excavator was lifted onto the top storey, where it began its descent to the ground floor, carefully pulling down the lumber on each of the four levels along the way.

While the bricks removed were sent for recycling, other salvaged materials were either sold or locally donated. The precious old-growth lumber was sold and shipped to a reclaimed-wood manufacturer in Montana.

But deconstructing a building to ensure that its components can be reused is only half the challenge. The other half, Corneil explains, is generating consumer interest in the salvaged materials.

Building owners tend to favour new materials because these are perceived to be more durable and cost-effective. But as consumers become more mindful of the pressures this mindset poses for a planet with finite resources, Corneil hopes the interest in reclaimed materials will expand.

“It’s cheaper to throw away and build new,” he says. “But that time is coming to an end, and we’re realizing that the circular economy is the economy of the future. We need to start rethinking how all of our processes and society work.”