An Iconic Stopover

Work-In-Progress Gander Airport’s International Lounge—and its proud history—is now accessible to the non-travelling public.

By Daniel Bromberg

Photos by Stéphane Groleau

Courtesy of Patriarche

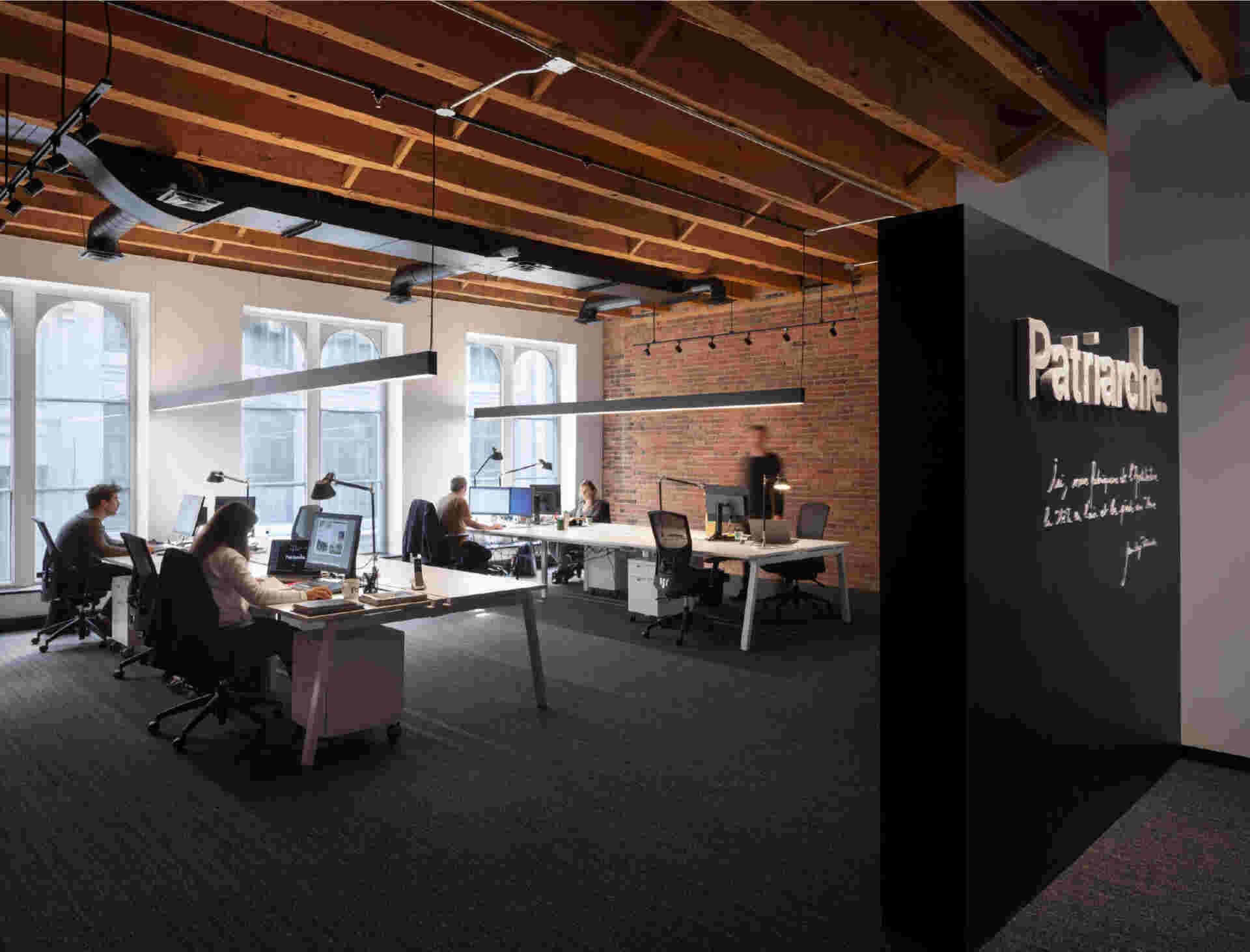

Patriarche’s employees share long rectangular desks surrounded by red brick walls and exposed beams overhead.

Stepping into architecture firm Patriarche’s Montreal office, one immediately feels transported to both the past and the future in a fusion of culture, creativity and functionality.

Located in Allied’s 85 Rue Saint-Paul Ouest building, which dates to 1861, the office was renovated before opening in 2019. When Patriarche was selecting the location for their sole Montreal branch (they have others in Paris, Bordeaux, Lyon, London, Basel and Quebec City), the historic quarter of Old Montreal was the obvious choice.

“It’s an attractive area for our employees to come and work every day,” says Luc Bélanger, partner and director of North American operations. “Not to mention, the idea of contributing to the preservation of a historic building, while reimagining its interior space, is part of our DNA.”

The multinational, multidisciplinary firm is composed of teams of architects, landscape architects, project managers, interior designers and graphic and user experience (UX) designers. When creating the interior of the Montreal office, Patriarche prioritized an open concept. Employees share long rectangular desks in rooms characterized by red brick walls and exposed beams that sweep the ceiling.

The company’s mission is to create what they call “augmented architecture,” integrating every ounce of technical, sociological and scientific knowledge available into the design process. In other words, for Patriarche, a physical space is not merely built and inert—it is, by necessity, an extension of the users and their needs.

As they did with their Montreal office, they do for their clients: Patriarche prioritizes open spaces in their projects, to encourage collaboration, and modern or natural lighting and green spaces to help drive productivity. “We do not even attempt to build something until we’ve tested the functionality of the space,” Bélanger says.

This aspect of their mission—consciously designing space around the user—is what they call “sobriety,” a term that president Damien Patriarche has called an unbreakable rule in their projects. Put into practice, it amounts to architecture that is simple, elegant, functional and humanizing.

This human-centred design approach extends beyond current users to future generations. Patriarche uses collective intelligence to do and build better, both on a day-to-day basis and in the longer term. “We propose architecture that unfolds in all its simplicity to limit our carbon footprint and ensure respect for social, environmental, economic and geopolitical contexts,” says Bélanger.

This is how Patriarche balances being a leader in its domain—outrightly refusing to be placed in a box—with the sober attitude required today to practise architecture (given that the building sector plays a principal role in global greenhouse gas emissions, waste production and energy and raw-material consumption). While seeking to ensure the economy of ambitious projects, Patriarche imagines sustainable, transformable and low-energy projects whenever possible—wherever they are on the globe—and makes them a reality.

“The preservation of a historic building, while reimagining its interior space, is part of our DNA.”

A quote from Jean-Loup Patriarche on the entrance wall says, “Here, we make (build/create/design/produce) architecture with our heads in the air and our feet on the ground.”

Patriarche’s mission is to use every bit of technical, sociological and scientific know-how available when designing a space. A current project is the management of the restoration of the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris.

A glassed-in conference room provides visibility and transparency in a shared office environment.