342 Water Street

They call it Gastown: 342 Water Street and environs

BY: Chantal Braganza

Photos by: Jalani Morgan

In March 2020, when the Ontario government closed dine-in service at restaurants across the province, chef Suzanne Barr and her team at Toronto’s erstwhile True True Diner froze what they could, split the remaining fresh produce and headed home. “We never considered doing takeout,” says Barr, who, since 2015, has led kitchens at the Gladstone and Avril and at her own Saturday Dinette and True True Diner. “We had a very high percentage of our staff who come from very vulnerable situations, and I didn’t want to put them in any more of a vulnerable place.”

After more than a decade in the industry, Barr is attuned to the ways that hospitality work is precarious, even unsafe, for the kitchen and service staff who keep what was once an $85-billion industry in Canada running. If anything, COVID-19 has laid bare many of the industry’s labour problems, issues that advocates like Barr have long been vocal about—the expectation of long hours for minimum wage, precarious schedules, a culture of sexism and systemic racism. “It just makes everyone consider: What is a restaurant? What does it stand for?” says Barr. “What does it represent for communities, cities—even countries?” She’s not even sure that restaurants as we know them—the way they’re funded, staffed and managed—should return.

When Barr turned 30, a close friend gave her a birthday gift that changed the course of her life: a weekend getaway at an ashram in upstate New York. In addition to meditating and taking stock of her life and career as a television producer, she was asked to volunteer in the facility’s kitchen. “It was a Pandora’s box,” she says. When she got home that Sunday, she enrolled in cooking school at the Natural Gourmet Institute; she soon quit her job to intern at an upscale restaurant in Hawaii. She was studying pastry making in France when she met Johnnie Karas, her future husband and business partner.

“It took me some time to realize there was a way that I could understand more about food as a source of healing,”

Early in her career, Barr focused on vegan cooking.

Ditching a career in television to become a chef was a major pivot, but it wasn’t entirely out of the blue. Her parents had grown up eating and cooking Jamaican cuisine—her father, in fact, cooked home meals for delivery with his own mother when he was a teenager—and both had instilled in Barr a love of food. And then the experience of caring for and feeding her mother after a pancreatic cancer diagnosis in the mid-2000s changed the way she thought about nourishment. “It took me some time to realize there was a way that I could understand more about food as a source of healing,” she says. Barr focused on vegan and whole-food cooking in her culinary education and early career but emphasizes its emotional power too. “For me, it’s my mother, my grandmother, my great-grandmother. It’s my connection to Jamaica, to Africa, to being married to a Greek man and his love for food. And the fact that my son will have the same.”

In 2014, Barr opened her first restaurant, Saturday Dinette, an east-end Toronto diner that was praised for its thoughtful, healthy takes on classic comfort foods: coconut milk mac ’n’ cheese, chopped liver and onions brightened with Madeira vinaigrette, chicken thighs baked in crispy chickpea crusts. Saturday Dinette was beloved beyond its cooking too. Globe and Mail restaurant critic Chris Nuttall-Smith called it “a diner like no one’s built in 60 years … a beacon in a snowstorm.” Eating there, he wrote, “felt like a neighbourhood get-together instead of a business transaction.” It was the kind of place where guests would walk in with vinyl selections of their own to play on the restaurant turntable during dinner and children’s strollers would be stacked up at the door. She focused on hiring diversely and launched The Dinettes, a training program for women keen on breaking into the industry.

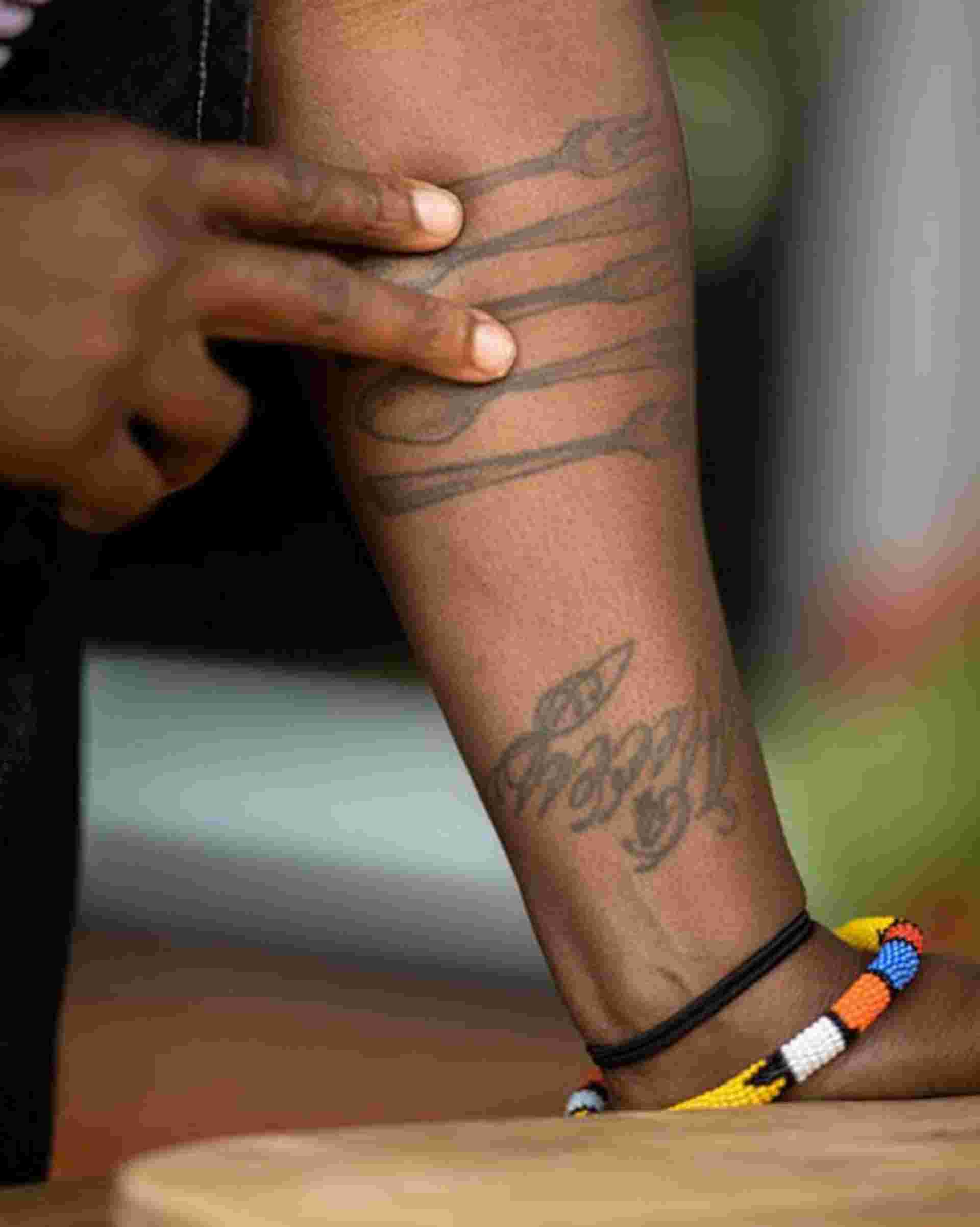

Essential chef tats.

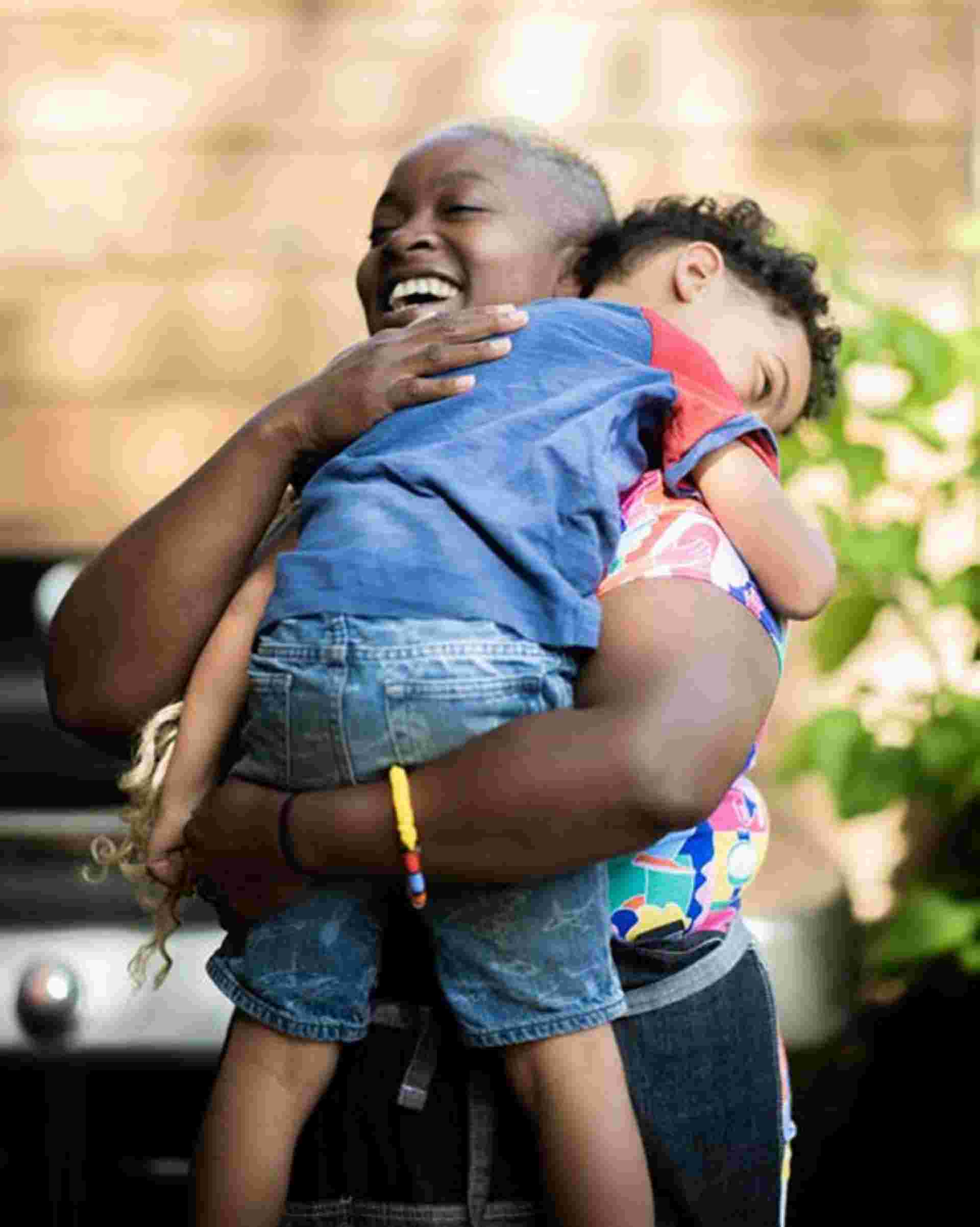

Barr with her son (affectionately known as her “sous son”) Myles.

Since then, Barr has made a point of paying her staff a living wage, splitting tips equally among teams and even investing in a health spending account for staff—measures that aren’t common in independently owned restaurants. She’s also made a point of honouring the threads of Black activism that informed her upbringing. It’s why Saturday Dinette and True True Diner have been modelled as diners—establishments with traditions of simple, affordable menus, accessible hours and a distinctly American role in the history of the Civil Rights movement. It’s also why, early in 2020, she launched For the Love Of, a monthly dinner series featuring Black chefs across the city.

Barr is also working on a cookbook for Penguin Random House that’s due out in 2021. She’s been at it for nearly two years, pulling threads from her own life, learning from her father as he made beef patties on the kitchen counter or watching her mother stuff fruits into a rolled-up paper bag to use for black cake, a prized Caribbean treat.

News that True True Diner would not be reopening broke in the summer of 2020—a decision that Barr says was made by business partners without her approval. “It wasn’t just this corner neighbourhood spot,” she says. “People felt it was their own. They owned it with me.” Hearing Barr speak of what has been lost sounds like a distillation of what she hopes more dining will look like in the future. “A concept that really focuses on not just the experiences of the guests but on your staff and team,” she says. “A place to go and feel like [you] are being entertained in a way that’s different from when you eat at home or your family’s home. That’s the essential and beautiful effort of a restaurant.”

Barr’s first dinner series featured custom menus by Bashir Munye and Adrian Forte, Somali and Jamaican chefs who have been cooking in Toronto for years.