Glenn Harvey

Fill In The Blank Glenn Harvey’s orb-like urban infill

By Ossie Michelin

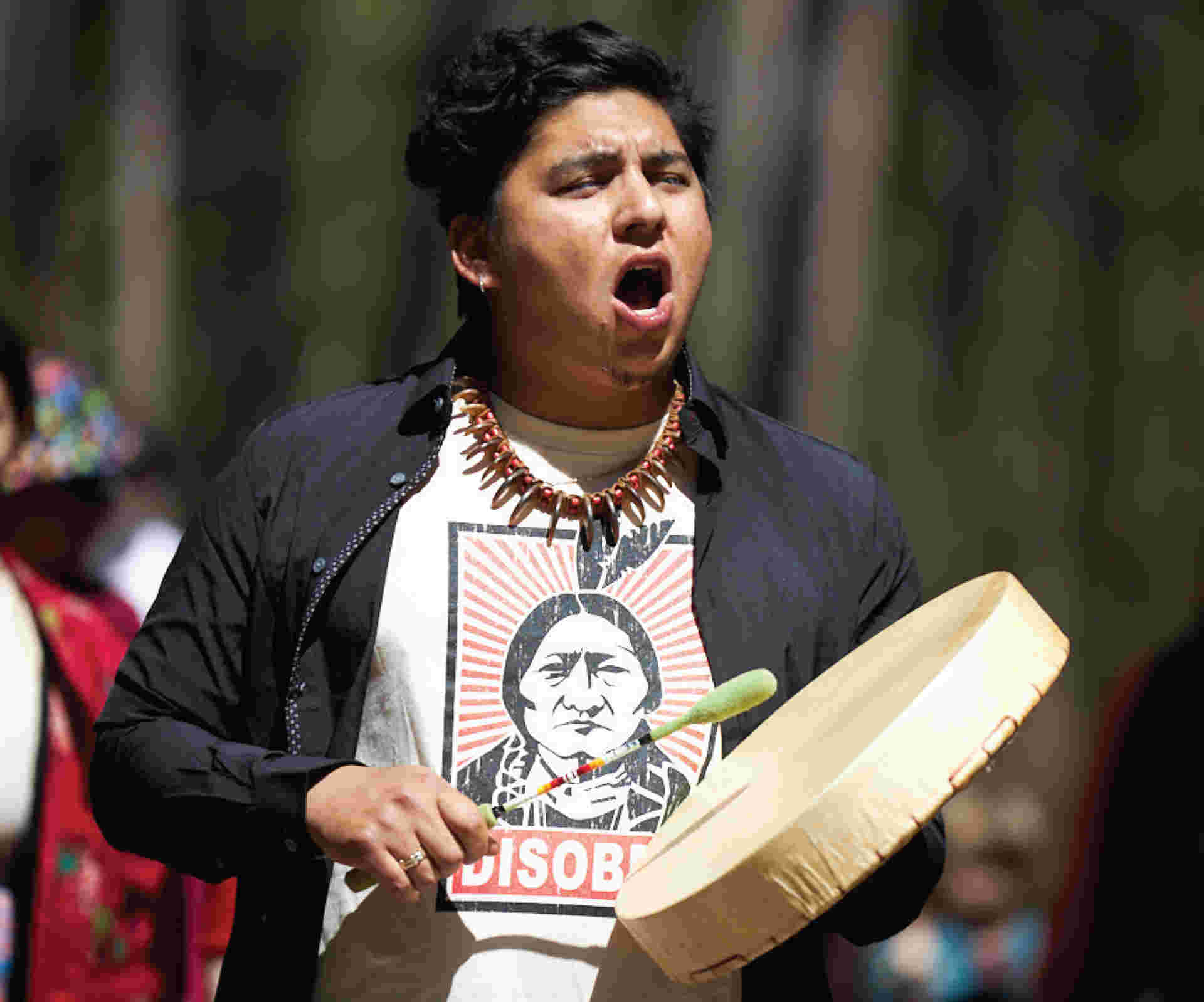

Photos by John Paillé

At the age of three, Nimkii Osawamick danced at a powwow for the first time, dressed by his mother in toddler-sized grass dancing regalia. The Anishinaabe artist from Wikwemikong—or the so-called Manitoulin Island—has since become a renowned hoop dancer and educator and recently secured a Juno Award nomination for a more recent creative venture: singing.

Osawamick says he is blown away that his group, Nimkii and the Niniis (“Nimkii and the guys”), is among the first-ever Juno nominees in the traditional category of the Canadian music awards show. “This is so exciting for me, as a kid who grew up in the powwows,” he says.

For Osawamick, that’s where it all started. The powwow drumbeat has been part of his life since that first tiny-tots dance at the age of three. At 13, he began performing at competitive fancy dances, one of the four cornerstones of powwow dancing. But It wasn’t until a couple of years later, at 15, that he found his calling.

“Hoop dancing changed my life,” he says with a broad smile. “It has made me see the world in a different way, and I have more respect now for all living things.”

Hoop dancing is a popular form of Indigenous dance and a powwow staple. The dancer performs with multiple hoops—sometimes more than 20—swinging and spinning them to the rhythm of the drum.

“It’s one of the greatest forms of storytelling,” says Osawamick.Dancers can go from dancing and spinning the hoops into a tight formation—all in the blink of an eye. By interlocking the hoops, they can mimic animals like the snake, bear or thunderbird.

“That’s what hoop dancing talks about: the plant life, the animal life. It talks about how our body is a link in the chain, and without any of these great nations that you’re seeing honoured in this dance, we wouldn’t be here today,” says Osawamick.

Nimkii Osawamick at McGinnis Lake in Petroglyphs Provincial Park.

Hoop dancers are often clad in intricate regalia that identifies who they are and where they come from. Regalia is highly personal, bold and colourful. Sometimes it’s made of organic materials like bone, shell and natural pigments. Or it can be bright, neon and made of synthetic materials.

When Osawamick was first learning to hoop dance, he used seven hoops and over time worked his way up to using 22. As he became more experienced, he realized the real challenge was doing more with less.

“There’s so much you can do with just three hoops and precise formations to tell a story,” he says. “As a performer who travels around, [I find it] a lot easier to carry six hoops,” he adds with a chuckle.

Osawamick says that growing up in the powwow community helped him connect with his culture, avoid drugs and alcohol and live a healthy life. After a lifetime of powwow dancing, he decided to try his hand on the other side of powwows, singing and drumming.

“I was always the dancer on the outside of the drum circle, and now I get to learn the beats and how all the songs are formulated,” he says, adding that learning to sing and drum has made him a better dancer.

Osawamick onstage in his fancy dance regalia with DJ Classic Roots at a 2018 festival in Thunder Bay, Ont.

and leading a hoop dancing workshop for youth as part of the First Fire dance program in Toronto.

For Osawamick, it was seeing hoop dancers collaborating with contemporary musicians and artists that really grabbed his attention. He says he felt that this blend of the contemporary and the traditional reflected his personality and helped him connect with wider audiences.

Throughout his career, Osawamick has shared the stage with iconic Indigenous artists like Buffy Sainte-Marie and DJ Shub (formerly of A Tribe Called Red). Last year, he collaborated with some of the country’s best choreographers and dancers in New Monuments, which showcased Toronto’s leading IBPOC (Indigenous, Black and people of colour) dancers and aimed to dismantle and heal Canada’s colonial history.

Aside from performing, Osawamick works on cultural mediation through his company Dedicated Native Awareness (DNA) Stage to help share Indigenous knowledge through dance and song. DNA Stage offers workshops on hoop dancing, powwow dancing, singing and more to give others the chance to learn about the Indigenous perspective through dance and song.

Osawamick singing and drumming at a Water Walk—organized by his mother, Liz Osawamick, and held annually on Mother’s Day—as a way of sharing water teachings with the community. “We walk for the ultimate mother, Mother Earth,” he says.

On Earth Day this year, Osawamick gave a workshop at the Ontario Science Centre. “I used hoop dancing to remind the kids that every living thing has a spirit that deserves respect,” he says, adding: “I especially love performing for kids. When I make a formation and their faces light up, I almost feel like a magician.”

But his performances are more than mere entertainment, or even storytelling—they’re a demonstration. He believes it’s important to see Indigenous people proudly expressing their culture, considering that Indigenous drumming and powwows were banned in Canada for generations. It was only in the 1950s and early ‘60s that Indigenous culture was decriminalized.

Osawamick says he sings to honour his elders, who fought to carry on their traditions and ways of life.