10310 102 Ave.

The 1KM Guide Icy cocktails and more wintery fun in downtown Edmonton.

By Queen Kukoyi, Nico Taylor and Quentin VerCetty

QUENTIN VERCETTY: I describe myself as an interstellar tree. I focus on growing. I focus on telling stories about the future and on being a knowledge keeper. I’m an artist, researcher and teacher simultaneously, and my practice doesn’t separate one from the other. The Canadian chapter of BSAM came out of the work that I’d been doing, trying to find like-minded people to create a platform for artists because I recognize the healing and transformative aspects of it. NICO

QUEEN KUKOYI: All of it is decolonial work.

NICO TAYLOR: What we stress is sharing—sharing what we’ve discovered, our knowledge, experience, skill sets. When we create things, we incorporate several different perspectives because we’re creating them together. We are trying to abolish and dismantle a singular way of seeing the world, allowing people to see things from the lens of their environment and their cultural understanding.

QK: The overarching framework we work from is the Ubuntu framework: I am because we are; without each other, we can’t succeed. In the Eurocentric lens, you have this idea of individualism. In the Afrocentric lens, it’s collectivism.

QV: But Afrofuturism from a Canadian standpoint is unique because we recognize and acknowledge that we are on unceded territories, and we honour those who are the original stewards of this land. So, coexistence is a big emphasis—and partnership.

“That’s where the visionaries come in, to etch out those pathways.”

QK: Our fates are tied. Black liberation is tied to Indigenous sovereignty because we are stolen people on stolen land. We both have experienced similar traumas and displacement. And there are so many linkages that don’t even involve colonialism—like our rituals and practices—that intertwine and intersect the two cultures. For instance, we’re doing a film that will be coming out in November called Rahyne. It’s about an Afro-Indigenous young person who’s also non-binary. In both [Black and Indigenous] cultures, there’s the importance of water and land and our connection to it, to ritual and our ancestors.

NT: I have a question. When we’re thinking about the future, is it the near future or 200 years down the road? What do we see as the future?

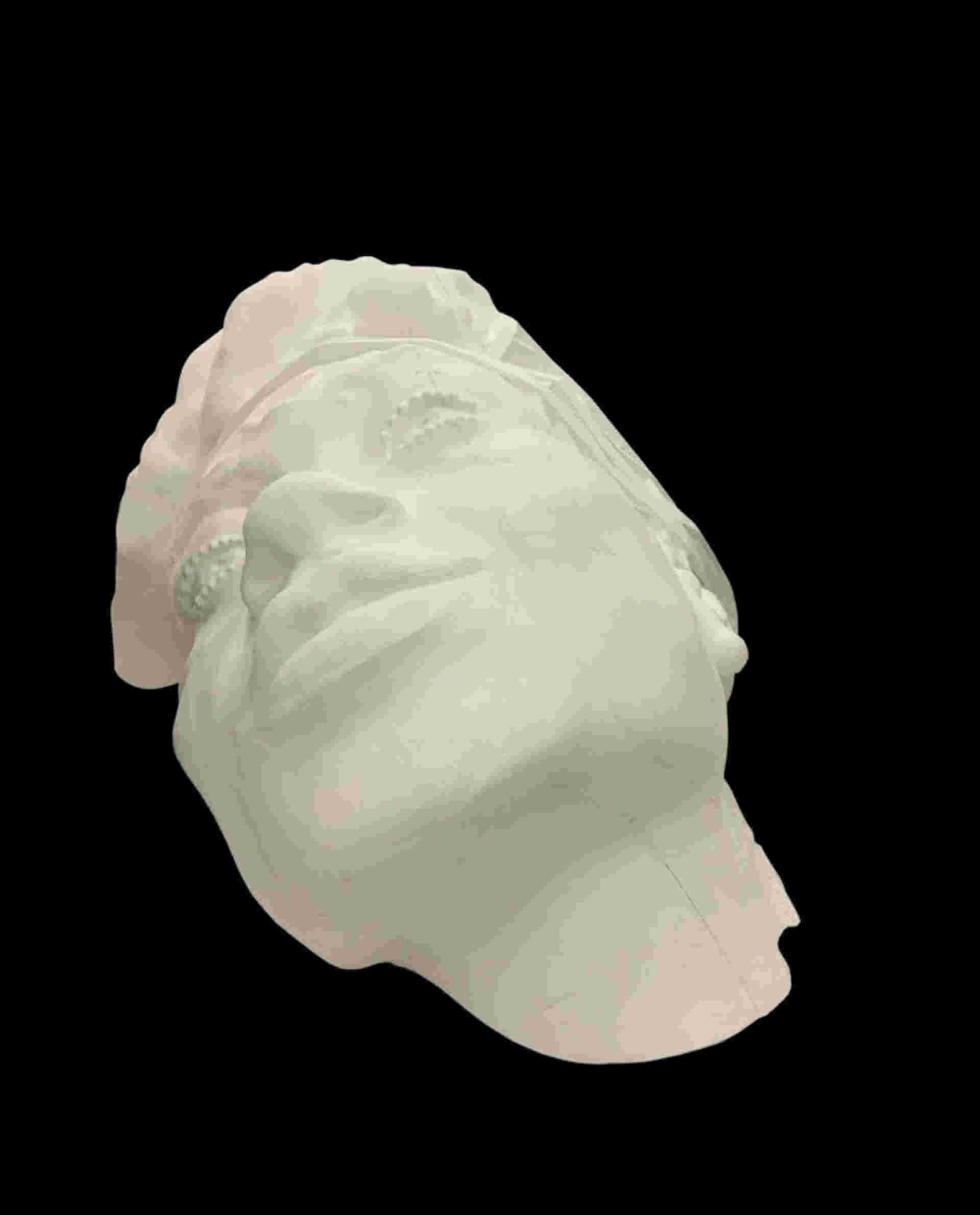

QV: For me, when it comes to art, I’m thinking about permanence and [creating] things that will last after I’m no longer here. That’s why I focus a lot on monuments and public art.

One of the biggest misconceptions of white supremacy is that monument-making is a Eurocentric practice, when the Nok people of [Nigeria and] Benin were making monuments out of terracotta around 2000 to 1500 BCE, thousands of years before the rise of Rome. I see a future that’s more inclusive in terms of representation and uplifting people of colour within the public sphere, with knowledge of the contributions of Black people to this country being readily accessible.

For example, people continue to think that the first Black people who came to Canada were enslaved. Schools don’t teach you about Mathieu Da Costa. If you don’t know, Da Costa was a translator with Samuel de Champlain’s party, translating between the Indigenous groups of Nova Scotia and the French. He came here as a hired linguist with his own boat and crew of people. That’s circa 1605, 20 years prior to the first enslaved African coming to Canada.

A lot of the research I do in my practice is around monuments in Canada. I’ve only been able to find 16 monuments of people of African descent (and there are all those generals, at least 20, lined up around Queen’s Park [in Toronto] alone). So, I made the 17th. The Joshua Glover bronze memorial is meant to last a thousand years before it needs mega maintenance. So, I’m looking at least a thousand years [into the future].

QK: My main theory of existence is parallel universes. So, for me, the future is happening simultaneously with the past and the present. I have Bipolar II and am very open about my diagnosis. It informs my way of thinking and my practice as well. I met with a spiritual healer, and he talked about it as an experience of my selves on different planes. A way for me to centre and ground myself in this plane is through abundance work and grounding exercises. But Quentin and Nico can attest to my thought process, assessing all these different scenarios within seconds—if we do this, then that can happen—which can be frustrating for them at times but is mostly useful, I like to think.

NT: I think it is useful! As for me, I don’t really think that far ahead— tomorrow is the future. So, when I create, I’m thinking about what the work could inspire today, maybe tomorrow, maybe the day after. I do things because they’re meaningful and because I see them contributing to a larger conversation. I imbue them with a hope that this conversation will end up being fruitful further down the line. I used to think I was an idealist, but being around Quentin and Queen, I’m beginning to learn I’m more of a realist. They’re the ones who dream big. But I appreciate that, because they’re the people we need to see beyond things like enslavement or bondage: for instance, to say, “This is not what life is—there’s more to what we are here.” That’s where the visionaries come in, to etch out those pathways.

QK: This is a hard conversation to have, especially with people in our community who can’t see beyond what they’re experiencing in the present. As a mother, I teach my daughter that our existence is filled with all these disparities and challenges but, like many of our ancestors realized, this ain’t it—there’s gotta be something better on the horizon. There’s an idea in Afrofuturism, in Black speculation, that you have to tear shit down to rebuild it.

NT: Or make it function differently by hacking it. I love this idea of hacking that comes from Afrofuturism. It’s taking the systems we know, going in there and tinkering.

QK: It’s understandable that a lot of young people, even adults, remain stuck, because when you’re living in it every day, it’s hard to see beyond it. That’s how trauma works, right? And the system is one big prevalent trauma that we experience on many different levels, whether we understand it or not. For those of us who’ve been able to so-called make it out—I don’t really like that expression, if I’m being honest—or those of us who’ve been able to think beyond what we’re currently experiencing, it was because someone or something (a person we met, something we read) helped us think alternatively

For more info on the Black Speculative Arts Movement, visit BSAMCANADA.CA and check out Cosmic Underground Northside: An Incantation of Black Canadian Speculative Discourse & Innerstandings, edited by Quentin VerCetty and Audrey Hudson.