Climate Intersects

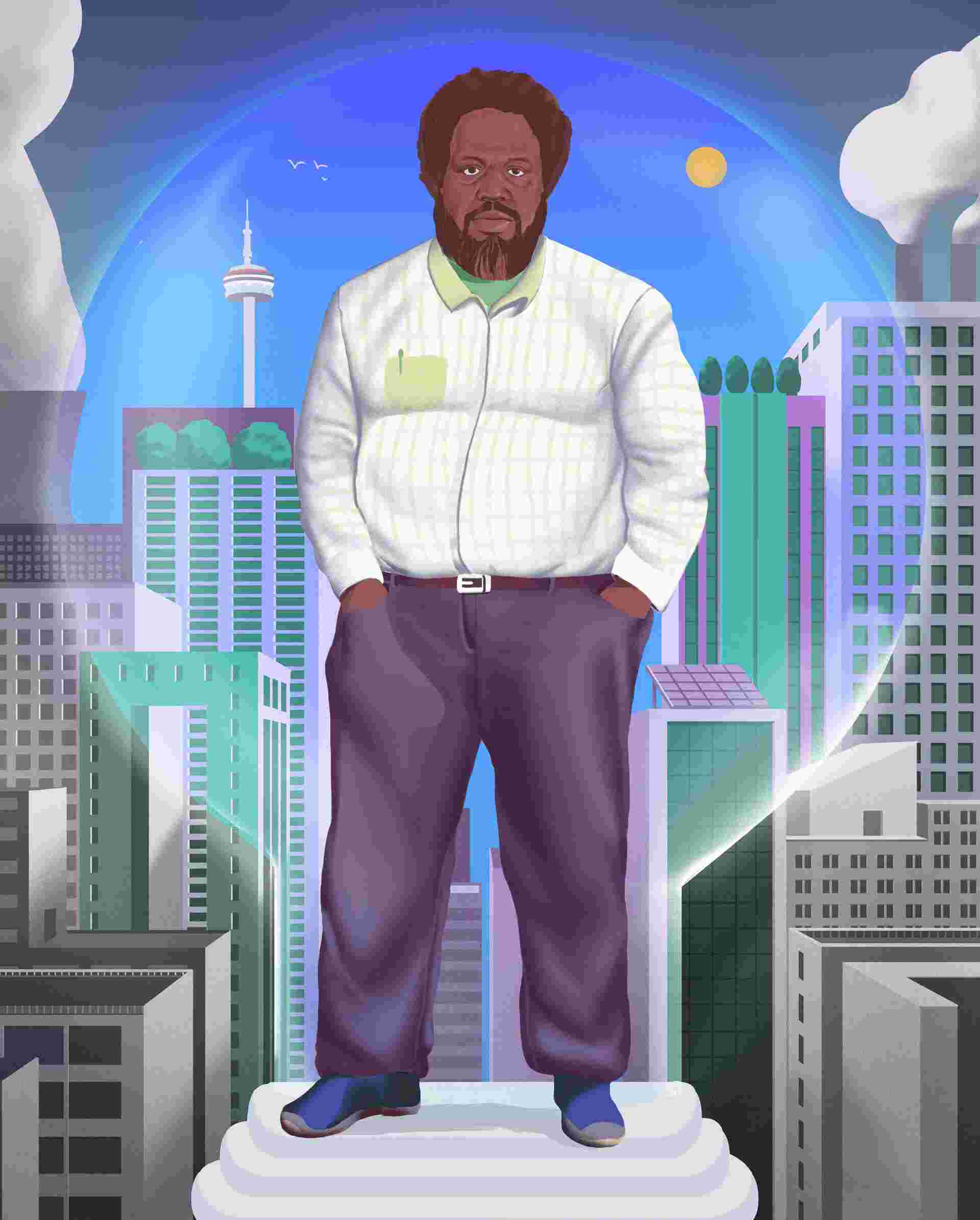

The Business The David Suzuki Foundation’s Julius Lindsay on climate, crime and community.

By Diane Borsato and Janalyn Guo

Collage by Diane Borsato with illustrations by Kelsey Oseid (2022) from Mushrooming: The Joy of the Quiet Hunt, by Diane Borsato and illustrated by Kelsey Oseid.

Mushrooms were The New York Times’ food of the year in 2022, and in January, the Mushroom Council—a very real council composed of fungi producers—said the trend is continuing. Diane Borsato, an artist and the writer of Mushrooming: The Joy of the Quiet Hunt, and Janalyn Guo, author of Our Colony Beyond the City of Ruins, spoke with Block about the “loathed and lusted after” kingdom Fungi, and how these organisms can help us pay closer attention to our environment.

Janalyn Guo: Diane, your book Mushrooming is a forager’s guide in a sense, but it also describes a way of looking at and being in the world. How would you describe it?

Diane Borsato: Mushrooming is essentially an uncommon field guide. It was written by an artist rather than a scientist, and it’s grounded in cultural conversations and contemporary art about mushrooms, nature, land and many other themes that fungi invoke, like death and decay, fairies and demons, aphrodisiacs and beauty. It is a work of love, really. I have learned a lot while walking slowly in the woods observing fungi. The “quiet hunt,” as it is sometimes called, has been a way to practise looking and seeing things closely.

JG: How cool to catalogue all the varied colourful fungi that greet you on your walks. They have their way of creeping into my work as well, maybe because they resonate with what I’m often thinking about: adaptation and resilience in the face of great environmental change, communication, connectivity and decay.

DB: A theme that seems to recur in your writing is an invasive nature—mushrooms or trees growing on or out of bodies calling us back to a natural environment.

JG: In my story “The Cave Solution,” a woman who volunteers to grow a tree inside her body finds herself able to communicate directly with the Humongous Fungus (a fungal mass in Oregon that once claimed the title of largest single organism on Earth). I am drawn to weird and mysterious things; since we know the least about fungi (compared to plants and animals), they’re very evocative to me.

DB: I love that she volunteers to grow a tree inside her body. It’s a beautiful image, though violent too—the most extreme imaginable level of a cross-species union. But why are mushrooms so villainous in your work? Are you fundamentally afraid of fungi?

JG: I think because there’s so much we don’t know about fungi, they haunt us. We fill in the blanks. They get tangled in our collective hopes and fears and anxieties. Some people proclaim that mushrooms are going to cure cancer and save the world. Then there are these works of weird horror, like The Beauty by Aliya Whiteley and Paradise Rot by Jenny Hval and the movie Matango, that all feature fungi and explore the notion of being overtaken, subsumed or changed in ways we can’t imagine that are beyond our control.

I mean, I wouldn’t mind being subsumed into a mushroom entity if it was helping us!

DB: It’s a striking image, though I think I prefer subsuming them, as in roasting and using them to garnish pasta. But you’re right about the mysteriousness of mushrooms and how they grow and reproduce. Imagine these beings that appear suddenly and grow in the dark. They don’t contain chlorophyll or act like plants at all. And they can cause frightening hallucinations, poisonings and a painful death. Fungi are a source of terror and fascination, feared and prized, loathed and lusted after—sometimes for the same reasons.

JG: For sure. I think mushrooms should have a spot in fancy tasting rooms, alongside coffee beans and wine and chocolate, where we talk about their terroir and mouth feels.

DB: I love that idea! So often, wild fungi are described vaguely as “earthy,” though there is as much diversity among mushrooms as there is among cheeses. Some are flowery or taste like apricots or cinnamon.

JG: I’m curious about how seeing things closely became important to your work. Was there a time when it wasn’t?

DB: As a visual artist, it is my main work to look at things closely. I noticed that walking in the woods looking for mushrooms was a great way to practise this. Identifying them also requires great sensory literacy, including touch and smell and taste—but especially seeing. You have to spot them, camouflaged in the leaf litter, and then attune your vision to see the subtlest shifts in colour, striation, luminosity… I bring my studio art students into the woods too and tell them it’s a practice of seeing a hidden kingdom.

JG: I recently started rockhounding in the desert, and I relate to this. I feel like it takes forever to zero in on that first rock, but after that initial discovery—once your eyes are attuned to that certain sparkle it gives off—you suddenly see them winking at you from everywhere all at once.

DB: This kind of attention to our immediate environment informs all of our thinking as artists. It contributes to our understanding of some of the most critical ideas of our time—that Indigenous scientists like Robin Wall Kimmerer of Potawatomi Nation describe as the urgency of expressing gratitude, living reciprocally with other beings and understanding how all our flourishing is mutual.

JG: Our human health and collective well-being are deeply connected to the health of the environment. When I write about trees and plants growing out of bodies, I just want to emphasize how much we’re connected.

DB: Mushrooming together with others in the forest brings a collective experience of this. If we are paying close attention, we might be present to ways in which land and weather are affected by colonial and environmental violence, to the wild diversity and wondrousness of living things and to our complex interdependence. To make contemporary environmental art, this experience and knowledge are essential.

Do you think writers and artists can have an effect on how we make decisions about the future of our environment?

JG: Scientists and activists are doing very hard and often unappreciated work on this front. I can’t claim to understand the truly complicated dynamics of an ecosystem, and I’m not directly interacting with and organizing people, but I do think that we as artists bring something of our own to the conversation. I think artists are evocative and perhaps a little bit sneaky. We can really surprise people into recognizing something true about themselves and their world when they least expect it. There’s something distinctive about that.

You can find Borsato’s Mushrooming in most major Canadian book retailers and online. Guo’s “Night Fragrance” appears in the anthology Mooncalves, published by NO Press.