Starting Block - The 10th anniversary of Block

Starting Block If you are an avid reader and consumer of Block magazine, first, thank you, and second, you may notice this issue is a bit different than the rest.

By Lourdes Juan and Marcin Kedzior

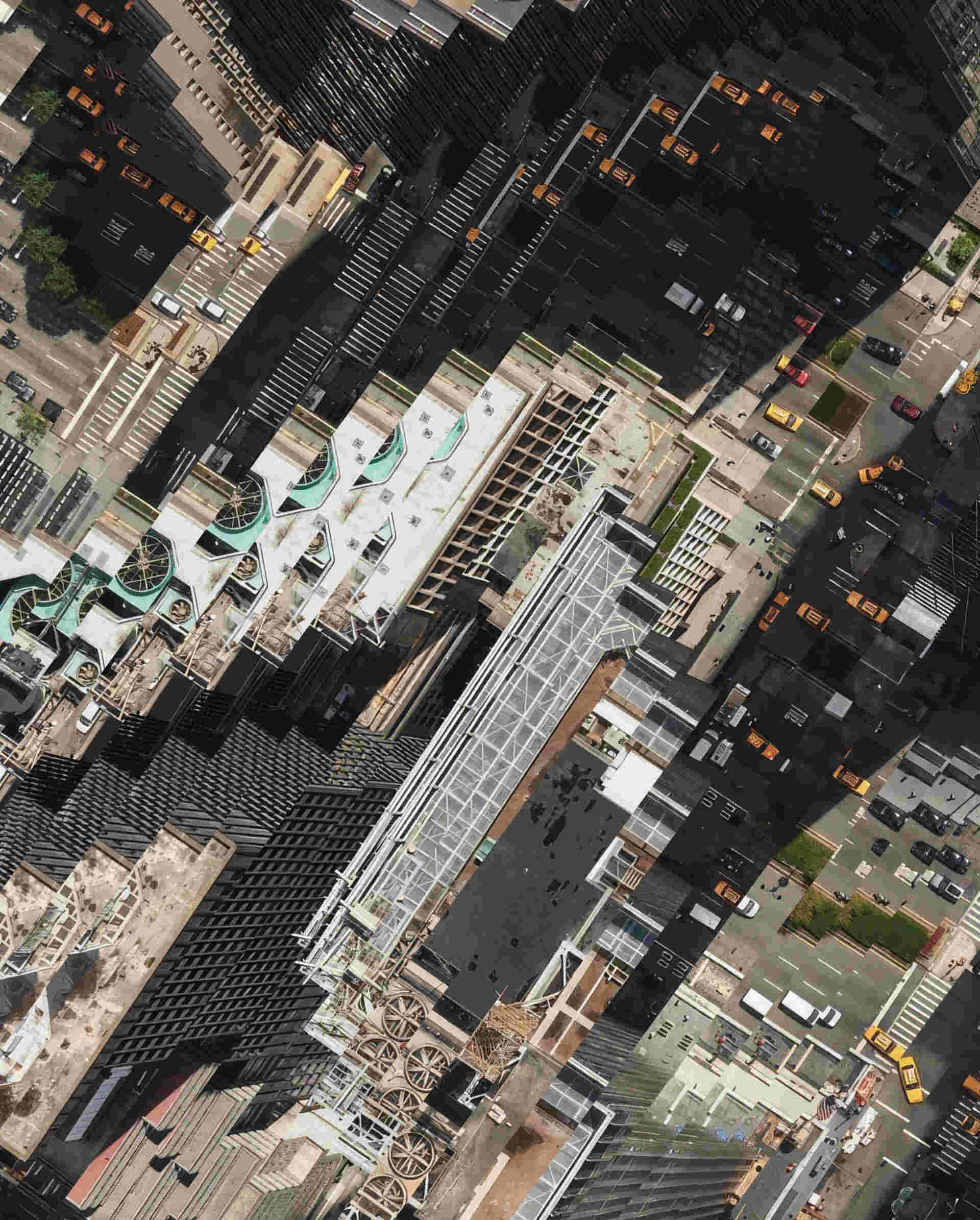

Photo by GS & CO

In an endeavour she calls “food rescue,” Lourdes Juan, an urban planner and the founder of Calgary-based Hive Developments, launched a tech start-up called Knead that connects the dots between food waste and organizations looking to recover it. She joined Marcin Kedzior, a Toronto-based design professional, educator and urban thinker, for a chat about urban planning as a mode of prophecy and how cities are designed versus how they’re experienced.

Marcin Kedzior: A recent obsession of mine has been thinking of the formation and inhabitation of cities from the point of view of rhythm — as a series of improvisations and responses that develop over time. Maybe every neighborhood has its own rhythm?

Lourdes Juan: I’m in Calgary — a city that is still in a very pimply-teen awkward phase — in a province that has been largely dominated by one industry, so we really haven’t had the opportunity to think about cool things like architecture and design until more recently.

I grew up here, and when I think of Calgary 40 or so years ago versus what it looks like today, in so many ways the city is making the right moves. For example, right now I’m sitting in Platform Calgary — a tech and innovation centre — and the floor heights are such that the building is convertible [to other uses]. In the future, we can turn it into offices or housing, and it’s right across the street from our [newly built] central library.

MK: That’s a great example of how certain buildings can set in motion the future of a neighbourhood or constitute a community or even a distinct form of living — especially if the design engages with the complexities of how people actually live, their everyday habits and practices.

LJ: When I think of making a true impact on a complex problem, it goes back to community engagement. We cannot take — and Marcin, maybe you’ve come across this in your design process — one idea or one architectural style and plunk it into a city. You really have to understand the roots and the context.

And you really can’t affect things like food waste, food security or food access without thinking about urban planning. When it comes to accessing healthy or affordable food, the [big box grocers] in Calgary are primarily in places that you need to drive to. If you are a young immigrant family, for example, and you don’t have access to a vehicle, or you’re a single mother and you have six children, or you’re a senior who lives alone, how on earth are you going to get to the grocery store that is an hour and a half away by bus. I don’t think it was done on purpose, but we’ve created these “food deserts” in the city. And also “food swamps,” in that there are lots of fast-food options in inner-city communities but access to healthy food like fruits and vegetables is almost non-existent. There’s a built-in inequity.

MK: That’s a great point about accessibility in the food landscapes you describe. Going to the market is — or should be — a pleasurable event, an amazing social and cultural experience.

Sometimes, in planning discourse, there is an emphasis on getting from point A to point B, but something about the richness of living in a city is harder to capture. When we talk about social cohesion, we often use musical terms like “unison” or “harmony,” but I don’t think those terms are as good as “polyrhythmic,” which describes when a rhythm is open enough to accommodate other rhythms to enter and become part of it — the tempos, speeds and possibilities of urban life.

I know Calgary has an extensive above-ground walkway system. It’s interesting the kind of co-operation that it took between different partners to create that circulation system. I would love to learn more about how you think about these things, how long it takes for things to improve in the city and how those relationships are nurtured.

LJ: There’s a political layer, then there’s this engagement layer with all who want to be at the table, then there’s a cultural layer. I remember doing a project in Chinatown here that was fairly controversial. In just a three-block radius, there were over 120 different community associations. It takes all these different layers to get [a full picture and] all the feedback. Then we sift through what’s helpful, what’s not helpful and where we can do better.

I wrote a paper in university about how the Plus 15 skyway network was the most inequitable system. Someone in my master’s program wanted to see, if they dressed a little scrappy, how long it would take to get kicked out of the walkway. I think the average was about 4.6 seconds. It’s pedestrianism for only certain folks, and that decision was made from a political standpoint. It’s like, we put time, energy and effort into making something that is not accessible for many people, who probably need that shelter from the cold. I don’t know how that’s going to play out in 30 or 40 or 50 years.

Like I said, we’re in an awkward phase. We can always envision what we want something to look like, but we’re really just gathering information from cities that we want to emulate.

MK: On the point of envisioning futures, I think that kind of analysis is like a mode of prophecy, done by the Oracles of Data! My rule of thumb has been that beyond 200 years is unfathomable, which is about the time frame between someone’s great-grandparent and great-grandchild. It does feel a bit controlling, trying to own the future before it happens by making predictions. Though I love what you said earlier, Lourdes, about building flexibility into the design of Platform Calgary.

LJ: Anticipation and optimism! I hope this building isn’t a parking lot in 50 years. I hope the library across the street is a historical building my grandchildren can enjoy. And maybe it will function differently, but the architecture and design will really stand.