10310 102 Ave.

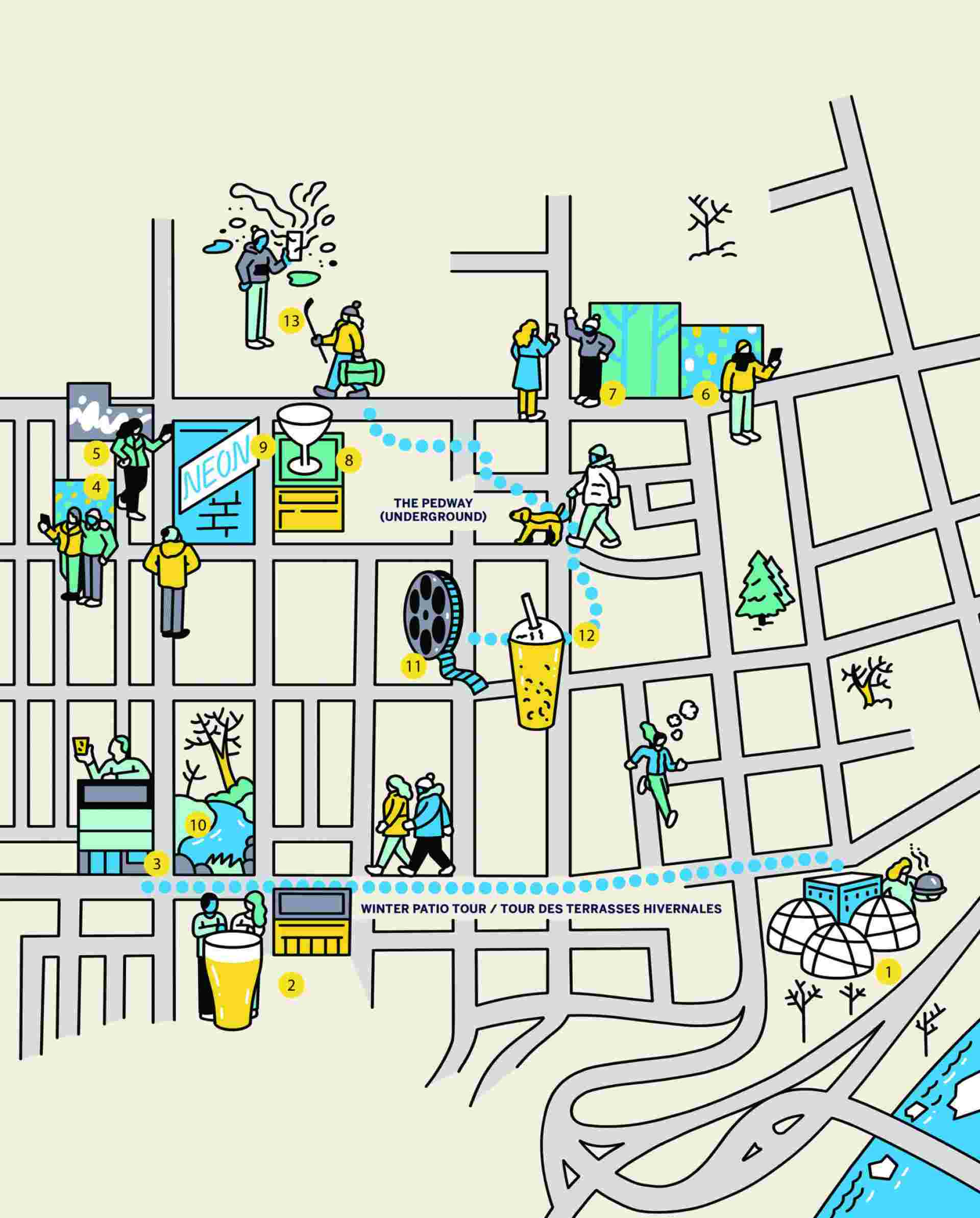

The 1KM Guide Icy cocktails and more wintery fun in downtown Edmonton.

By Kristina Ljubanovic

“There’s no other place anywhere like Ontario Place,” proclaimed an early publicity brochure from the Ontario Place Corporation.

Hackneyed maybe— but also the truth.

Situated on Toronto’s waterfront, Ontario Place, with its artificial islands, 460-metre seawall created by sinking three lake freighters, triodetic dome structure (home to the world’s first IMAX cinema) and seemingly floating pavilions, is an original— a modern icon that stands apart as a rare built example (and very likely the only one constructed on water) of a particularly utopian style of modern architecture and ecological landscape design.

The park and attraction celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2021, but it’s currently under notice, subject to closed-door redevelopment moves by the provincial government that have been criticized by architectural aficionados, those with fond memories of what Ontario Place was in its heyday (and can still be) as well as proponents of transparency and due diligence of public officials and processes.

Enter Aziza Chaouni, a Morocco- and Toronto-based architect and professor at the University of Toronto, and Bill Greaves of Architectural Conservancy Ontario (ACO). The duo registered Ontario Place for the World Monuments Fund’s 2020 World Monuments Watch, a biannual survey of endangered cultural sites around the world. (That same year, the listing included Notre-Dame of Paris, Easter Island in Chile and the Sacred Valley of the Incas at Machu Picchu.)

With the WMF’s support, Chaouni and Greaves assembled an advisory board of design heavyweights, including Margie Zeidler, daughter of Eberhard Zeidler, Ontario Place’s visionary architect. Calling themselves The Future of Ontario Place Project, they published an open letter “denouncing the fact that the government’s process was opaque, [given that] any redevelopment would be paid for with public funds,” says Chaouni, and gathered hundreds of signatures of support.

In response, the government announced it would preserve the Cinesphere and the pavilions—but for Chaouni, this wasn’t enough.

“Once we studied Ontario Place and the landscapes of Michael Hough—he was the father of modern landscape ecology, so even the landscape is heritage—we learned that it’s a ‘complex,’” says Chaouni, or gesamtkunstwerk, “a totally integrated landscape, architecture, infrastructure and environment,” as Greaves calls it. “If you compromise any of it, you’ve lost the soul of the place,” Chaouni explains.

But Chaouni, who’s concurrently working on conservation projects at the Sidi Harazem thermal baths in Morocco and the international fairgrounds in Dakar, Senegal (both massive and modern complexes dating from a similar period), contends she is not anti-development.

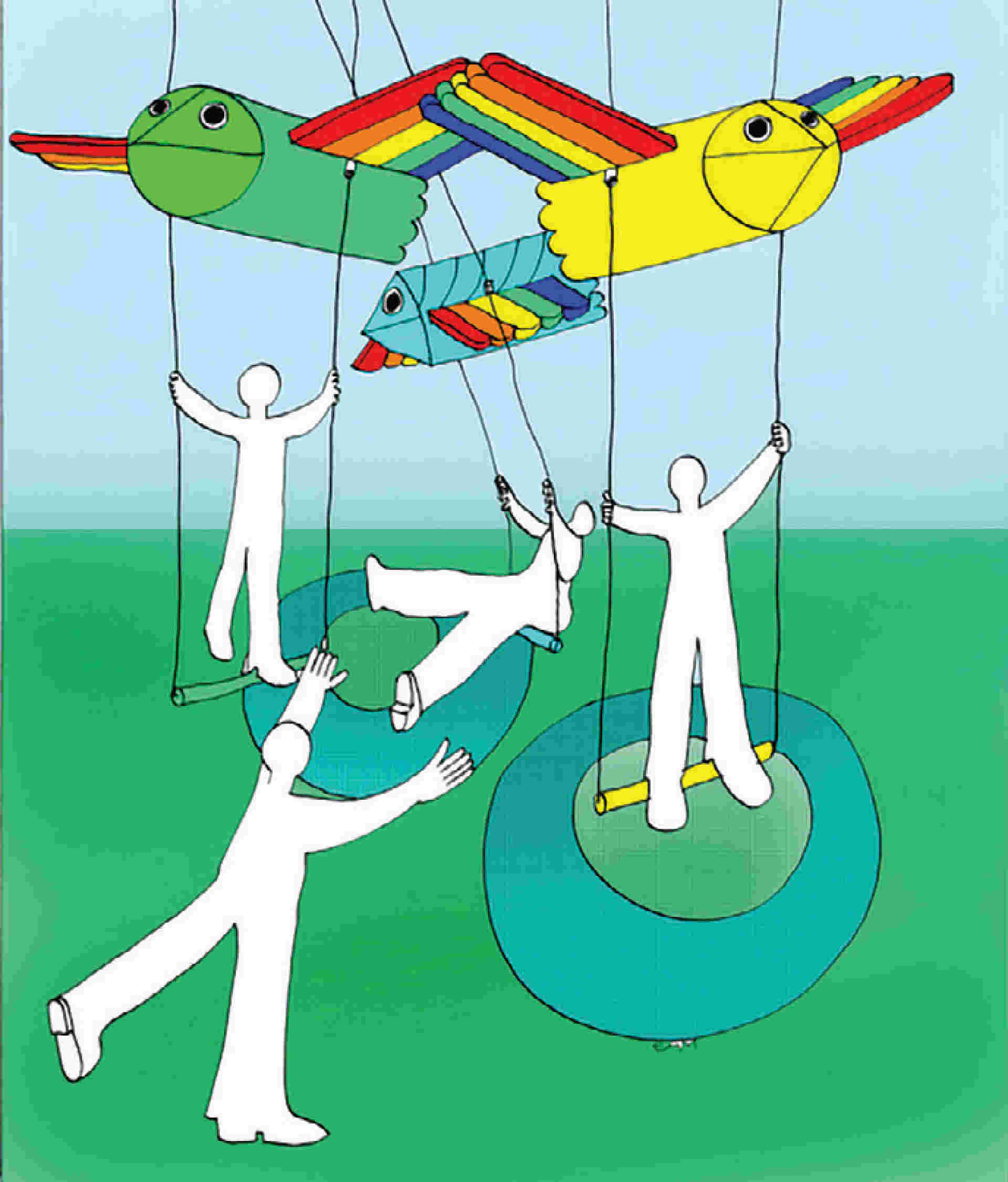

Designer Eric McMillan, the “father of soft play” and inventor of the ball pit, designed the original Children’s Village play structures.

Images courtesy of Margie Zeidler.

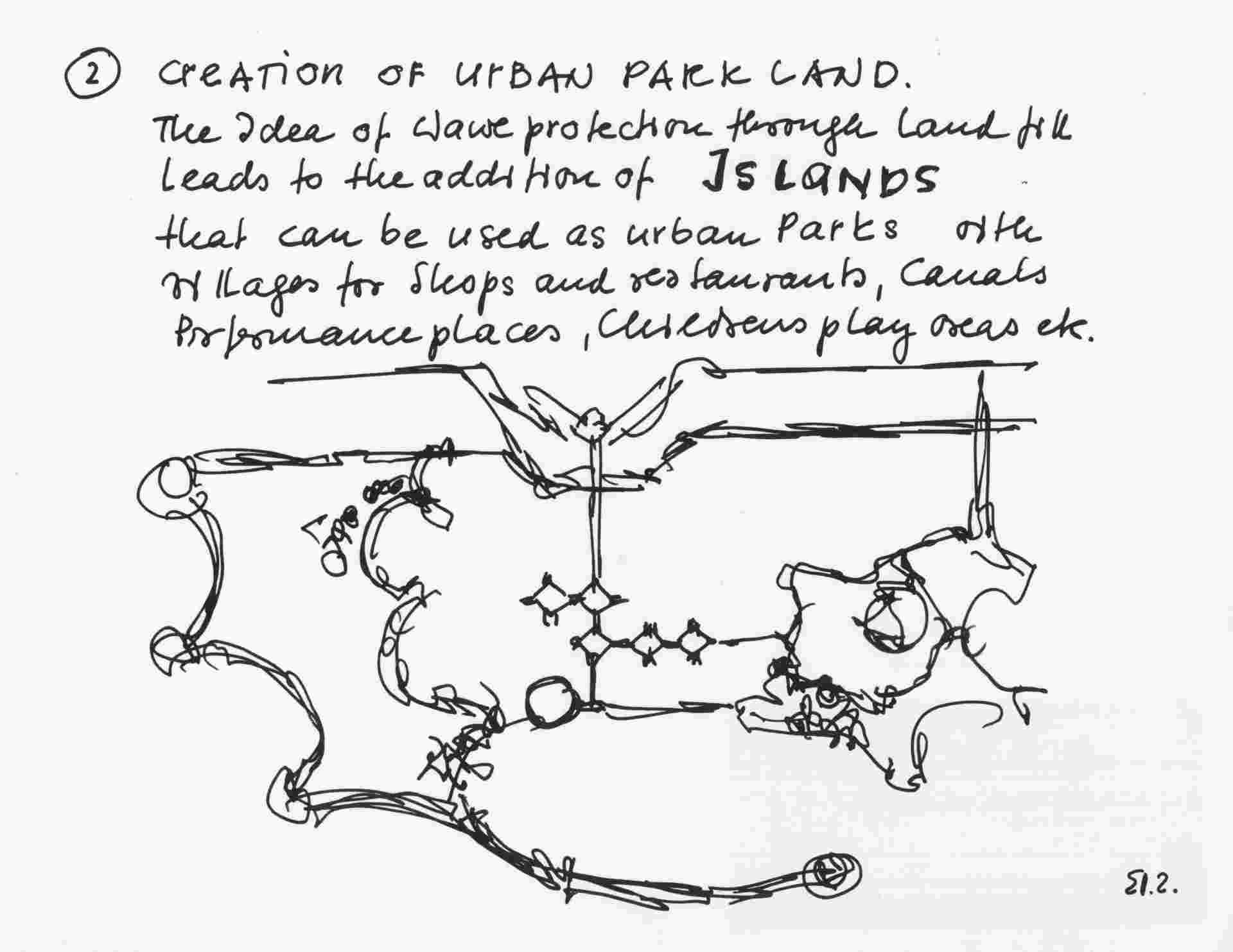

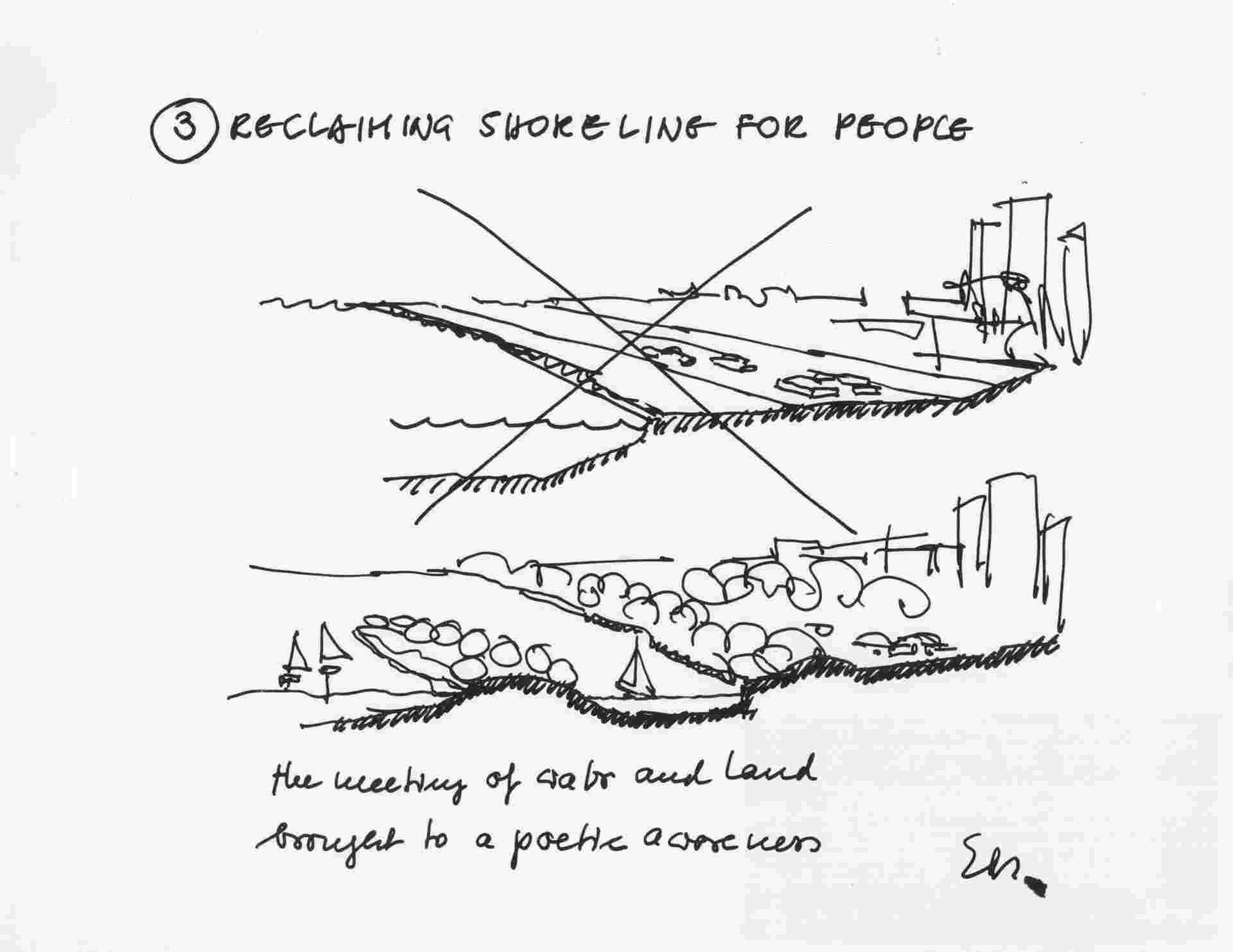

Architect Eb Zeidler conceived of Ontario Place as an urban park for the city, readily accessible to the public (and giving said public access to the shoreline).

Images courtesy of Rose and Eric McMillan

Photos courtesy of City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 200, Series 1456, File 361, Item 3; Photos courtesy of City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 200, Series 1456, File 360, Item 6; Photos courtesy of City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 200, Series 1456, File 360, Item 10

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: The exhibition pods (made from trusses hung from suspension cables), connecting bridges and fire stairs seemingly float above Lake Ontario; a view to an eating area from Marina Village; buildings were constructed of folded plywood to create complementary crystalline forms.

Photos by Andreea Muscurel

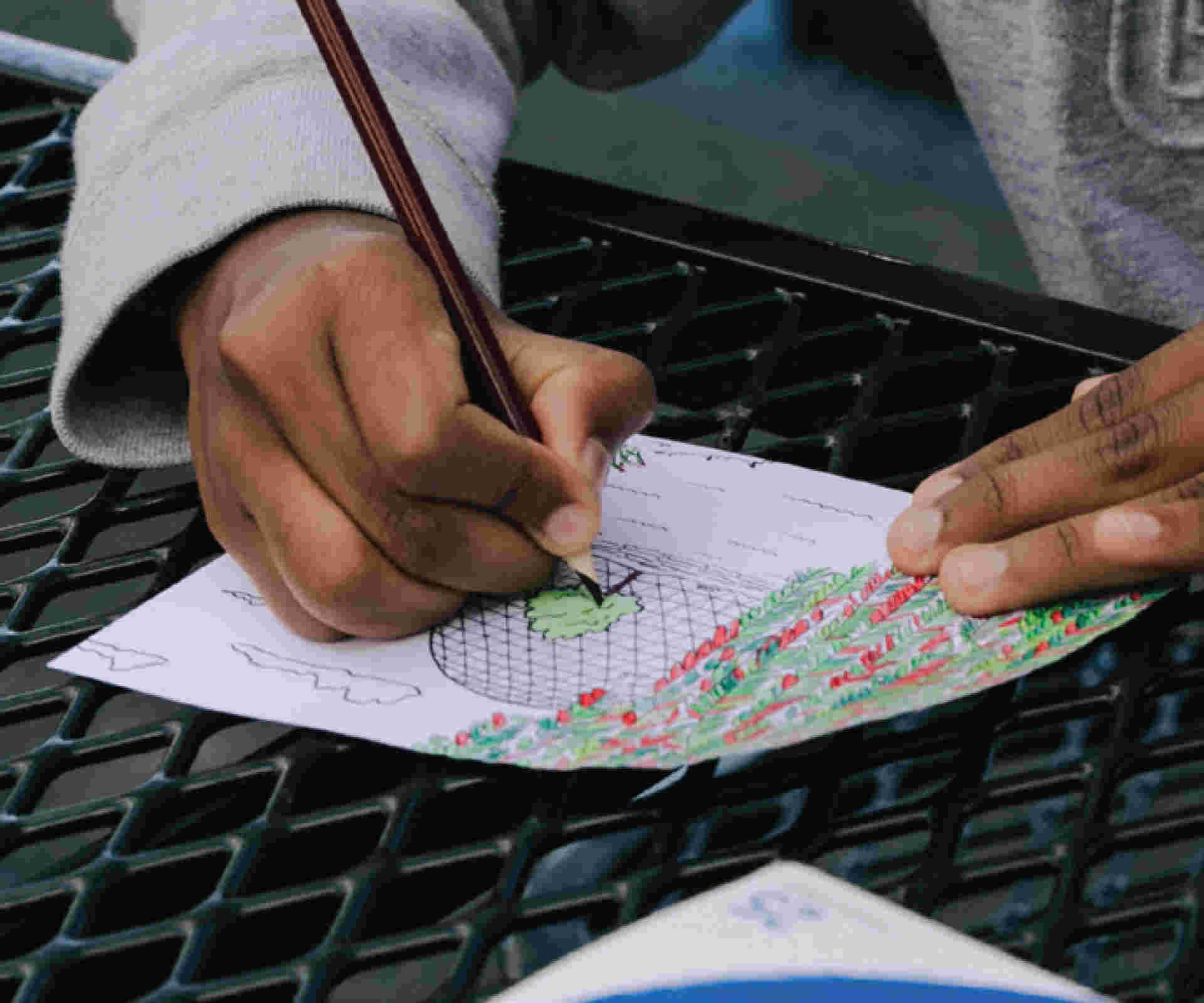

Drawings and documentation from the ACO’s Watch Day event.

“That’s a very clichéd view of conservation. Now, conservation includes retrofitting and adaptive reuse and programming that works within an overall vision. It’s not this ad hoc thing,” Chaouni says, referring to the piecemeal proposals selected for Ontario Place.

The Future of Ontario Place Project has created an online repository of user interviews and archival materials and has initiated a national ideas competition, garnering submissions from multidisciplinary teams of students from Canada’s schools of architecture. In late summer, the ACO held a public engagement event that asked people to imagine their future Ontario Place and capture those visions on postcards, which were then forwarded to the government.

While Greaves thinks the government’s scheme will ultimately “flop” without the appropriate buy-in, the group’s valiant efforts continue. Part of the challenge of the project is drumming up awareness of Ontario Place’s importance in the architectural canon.

“Twentieth-century heritage, what I sometimes call the heritage of our recent past, faces a lack of appreciation because it’s too young for some people to understand its value,” says Javier Ors Ausín, a project lead at the WMF.

And years of neglect take their toll. “If you don’t have a vision for a place, it’s going to fall apart,” Chaouni says. “But that’s not a justification to get rid of it.”

“It’s actually hard to overstate how important [Ontario Place] is. It’s an idiosyncratic and iconic and rare example of late modern architecture,” says Greaves. And beyond that, “it’s a beloved place for many people locally,” says Ors Aus n. “Everyone, no matter where they come from, can have access to the waterfront through Ontario Place. That’s what’s really important to us.”

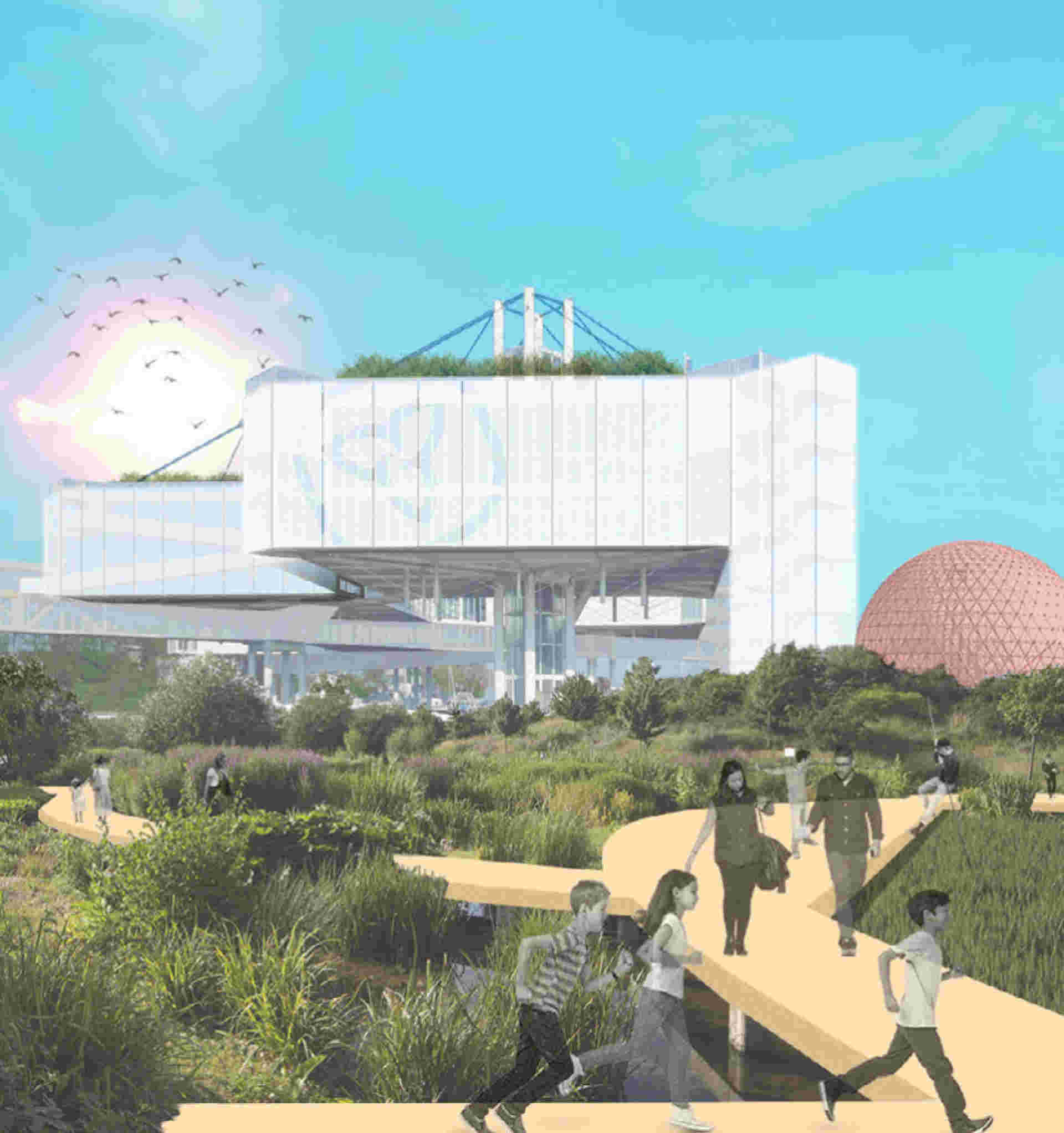

A proposal for Ontario Place’s pods that provides access and “free play” opportunities through the introduction of a wetland and boardwalk system, by University of British Columbia students Blaike Allen, Michael Monaghan and Kathryn Pierre.

The jury prize winning student proposal, titled Megalandscape Ontario, by University of Toronto graduates Catherine Howell, Ramsey Leung and Joseph Loreto, proposes a flexible, phased and longterm framework for development involving the Exhibition Place grounds to the north and inclusive community consultations.

Images offertes par The Future of Ontario Place Project