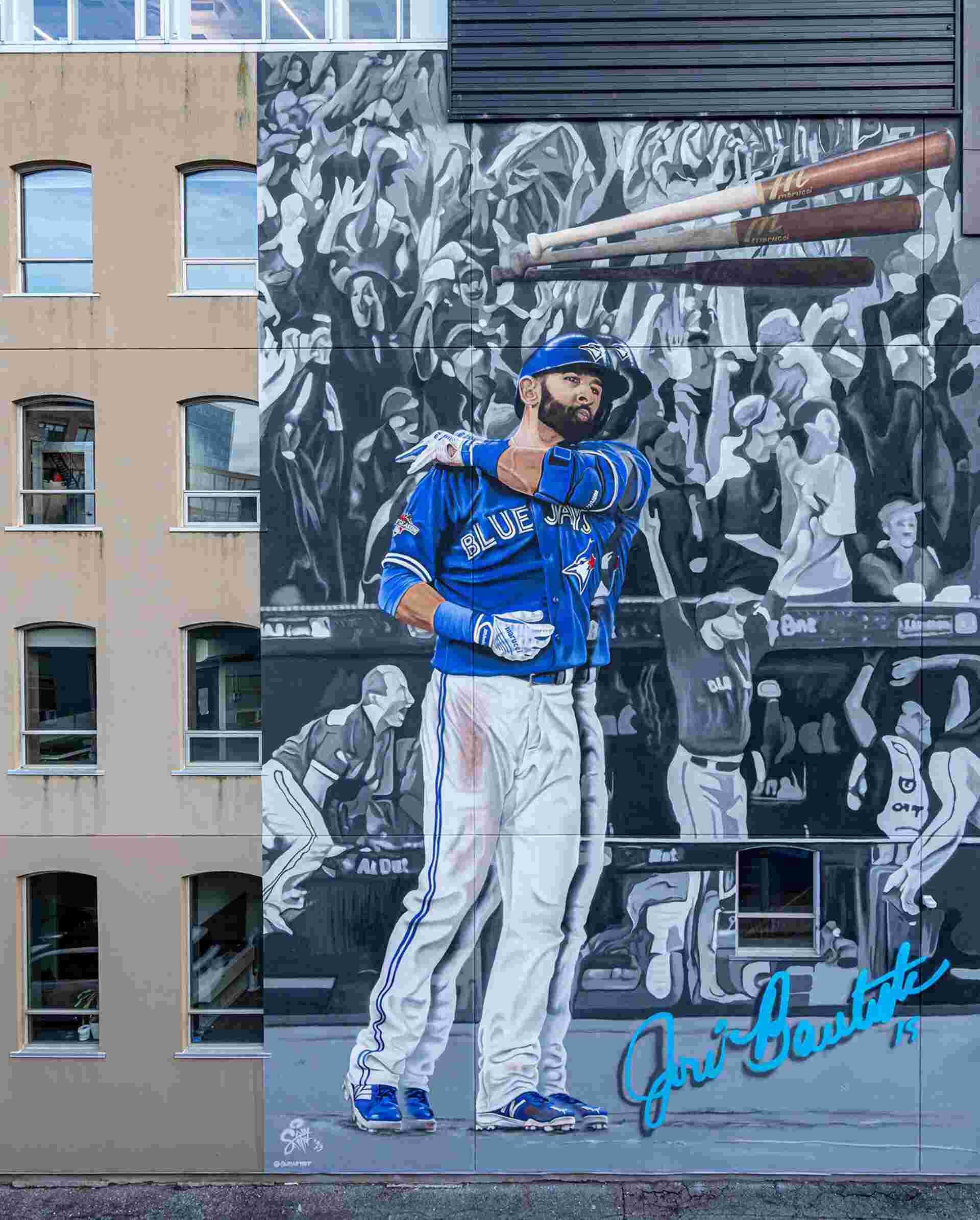

Freeze Frame

Make room for the arts Sum Artist’s José Bautista mural at 99 Spadina.

By XIMENA GONZÁLEZ

Photos by: ALANA PATERSON

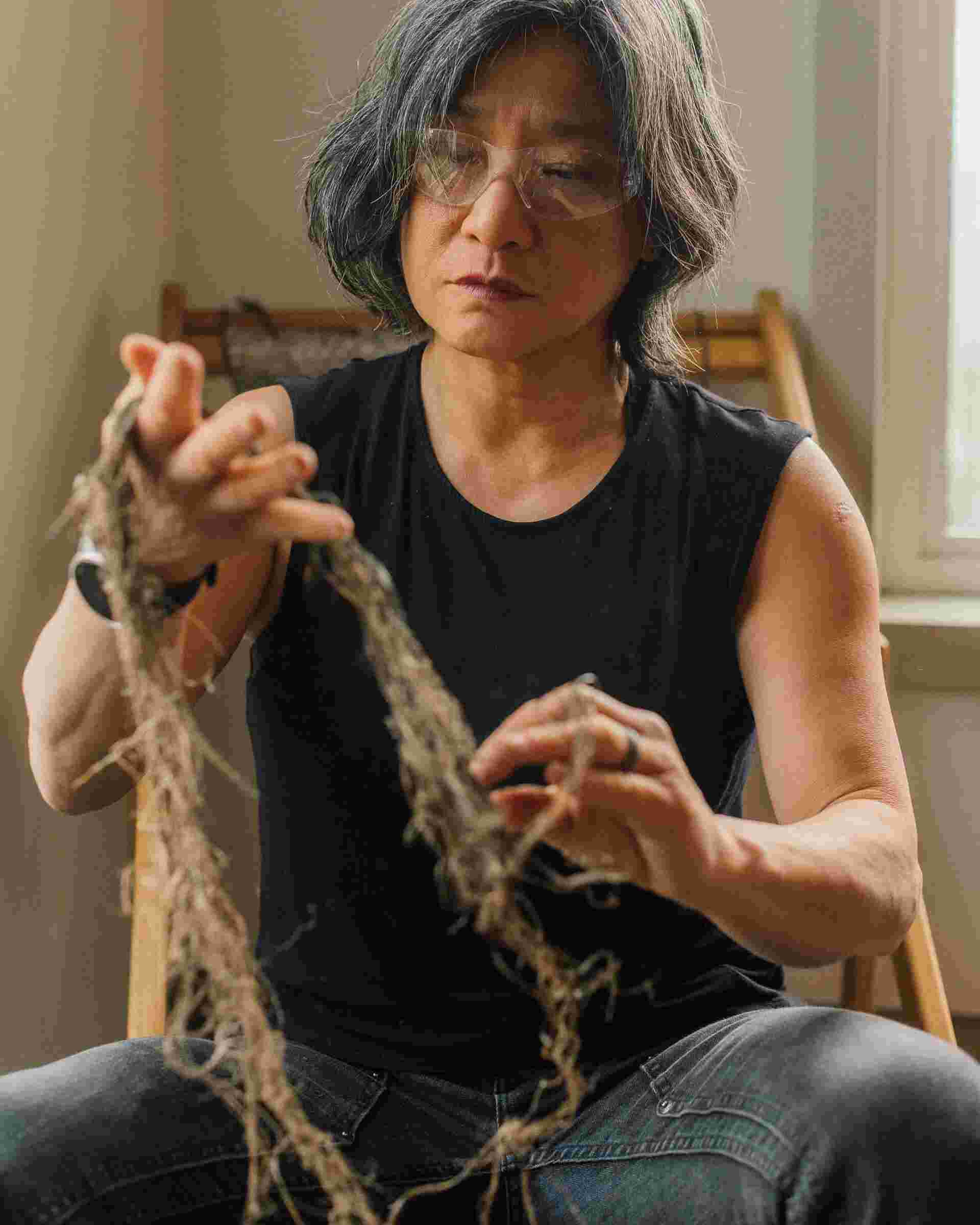

A vast and eclectic portfolio conceals a common thread that weaves Germaine Koh’s work together: she finds parallels where others see divergence.

“I first got into art because I was a person who wasn’t prepared to specialize in a single topic,” says Koh, a visual artist and organizer based in Vancouver.

In one of her public art pieces, Still Flowing, the wind blows a series of aluminum pennants hung atop a grouping of flagpoles, emulating a school of fish in the nearby Still Creek, in Burnaby, B.C.

After 35 years of uninterrupted artistic practice, and with a recent Governor General’s Award in visual and media arts under her belt, Koh is a staunch generalist, and her drive to explore new realms remains unquenched.

A few years ago, Koh reimagined a public bench at a Vancouver bus stop as a teeter-totter, reminding transit users of the importance of collaboration. In at least three galleries she’s installed an intricate system of stainless-steel stanchions with velvet ropes that, connected to a nearby body of water via sensors, move up or down following the tide. “The way this works serves to connect us to the world outside that our buildings usually go to great lengths to insulate us from,” Koh explains.

By extrapolating the ubiquity of the familiar, Koh’s installations bring attention to our connection to the environment, and each other. She achieves this in subtle ways, often through play. “The underlying ethos behind my work is an attempt to suggest that fields and phenomena that may not seem to be connected in fact have similarities,” Koh says.

“What my work ends up doing is trying to create situations in which we realize that maybe we’re not so disconnected from other people as we feel sometimes.”

Koh is part of Community Fabric, an ad hoc collective of artists, curators, and textile and costume designers from diverse cultural backgrounds who practise amateur weaving as a form of community and to create space for conversation.

Sometimes the connections made by spectators take Koh by surprise.

In Overflow, Koh used damaged, refundable glass bottles to evoke the invisible economy of East Hastings, in downtown Vancouver. But passersby saw more in the glistening, neatly arranged bottles. “It got adopted by the neighbourhood as an unofficial memorial to victims of substance abuse in the Downtown Eastside,” she says. “Because these bottles have a sort of elegy feeling, [they] stand in for people.”

As a generalist or jack of all trades, Koh relies on the expertise others share with her to bring her ideas to life, she says. “One of the things that is really satisfying to me—and the reason I move between realms—is to learn new things.”

A decade ago, Koh created a smartphone app for Marpole, one of Vancouver’s oldest neighbourhoods, to display the area’s lesser-known history as a food-source hub. The community’s past and present overlap in interactive map layers outlining former hunting and gathering spots essential to First Nations trade, and edible plants and soup kitchens in place today.

For WARES, a 2023 installation Koh characterizes as a quasi-fashion line, she learned from traditional weavers how to make fabric from scratch. More recently, she put on a hard hat and steel-toed boots to build an artist community on Salt Spring Island, where Koh and her partner own land. Her entrepreneurial spirit is evident in this endeavour. “I pose as if I am a property developer,” she says. “But I’m actually focused on small-scale, self-built buildings.”

Home Made Home, now a social enterprise that builds micro-homes and studios for artists, has slowly become central to Koh’s practice, as she’s seen too many colleagues displaced by Vancouver’s insatiable redevelopment.

The official launch of this ongoing project dates back to 2014—though inklings of it can be traced to the early 2000s—evidenced in an ever-growing number of installations constructed in collaboration with a group of like-minded folks. “The project is an umbrella to advocate for alternative forms of housing,” Koh explains.

Photo by Alana Paterson

A 2008 installation at the Vancouver Art Gallery showed changing tide levels and was streamed over the internet

Photo by Alana Paterson

The Home Made Home: Lululiving structure en route to be exhibited at Richmond Art Gallery

Her research on vernacular housing led Koh to learn that a home can be constructed by its users, and it can take the shape they desire.

“A hundred years ago, houses were not being built by specialized builders,” she says. “They were built by the families who were going to live in them.”

“One of the things that is really satisfying to me—and the reason I move between realms—is to learn new things.”

Home Made Home proves that everyday spaces and unassuming structures can become rooms for dwelling in, a community even. Koh shows this by experimenting with different materials, forms and locations.

She’s used salvaged construction materials to build a movable kiosk and scrap textiles to erect a tent in Toronto’s Small Arms Inspection Building. She’s reimagined the phone booth as a timeless, multi-functional space. She’s even found space to build a home over a gallery’s entry threshold and inside a wall, something Koh calls a “parasitic” installation.

“There’s way more room to sustain different kinds of housing in our world than we are necessarily willing to admit,” she says. “It’s just a matter of political will, whether we let those things exist.”

Koh’s weavings use recuperated or home-grown fibres and plastics

Photo by Germaine Koh

and Overflow, a site-specific process-based project at Centre A and in collaboration with United We Can bottle depot.