Freeze Frame

Make room for the arts Sum Artist’s José Bautista mural at 99 Spadina.

By: Kristina Ljubanovic

PHOTOS BY SAFOURA ZAHEDI

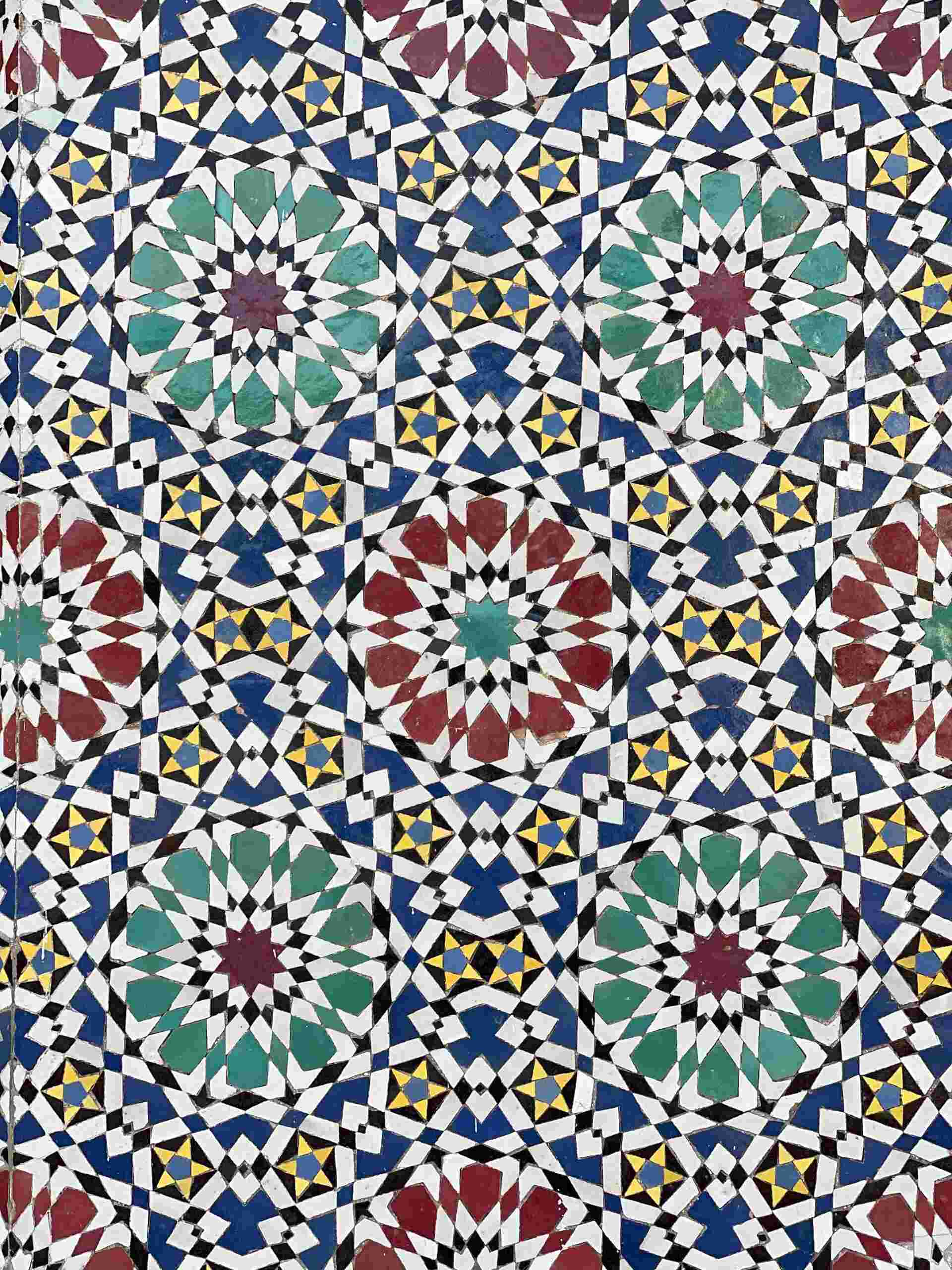

When she thinks back to her childhood, architect Safoura Zahedi sees geometrical patterns, fractals and arabesques unfurl behind closed eyelids.

A product of a beautiful mind? Yes, and a mother who’s an artist and graphic designer. “I remember she had this book, which she compiled herself over the years, of all these different patterns she had collected,” says Zahedi. “In graduate school, every time I would get stuck or needed a moment to creatively meditate, I would take the book and flip through and let my eyes blur into [the patterns].”

While Zahedi’s parents hail from Isfahan in Iran, once the capital of Persia under the Safavid dynasty and a cradle of culture and innovation in the region, she was born in Japan (also known, putting it mildly, for its design legacy).

Her pursuit of geometry was almost preternaturally determined; a birthright.

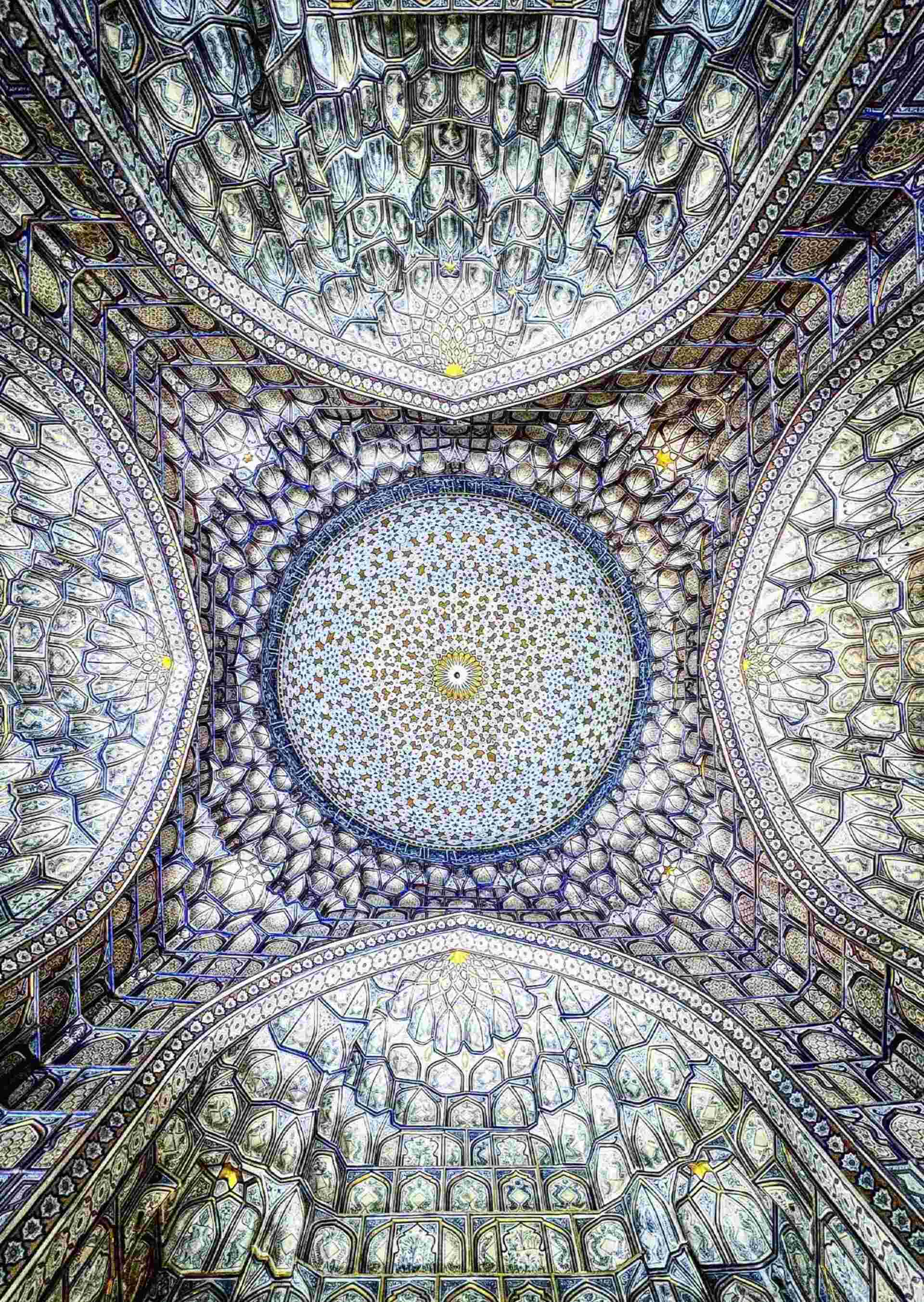

“For me, it’s not so much the nostalgia of it but the wisdom we can build on,” says Zahedi. Her own architectural thesis compared (and critiqued) contemporary Islamic architecture against the historical context, which saw “very sophisticated spatial manifestations of the geometry,” much of it coinciding with the mathematical and scientific innovations of the Islamic Golden Age from the eighth to 16th centuries.

“There is a lot to learn from the heritage and material culture that can then inform digital craft and today’s architecture using contemporary tools, digital fabrication and computational design,” she says.

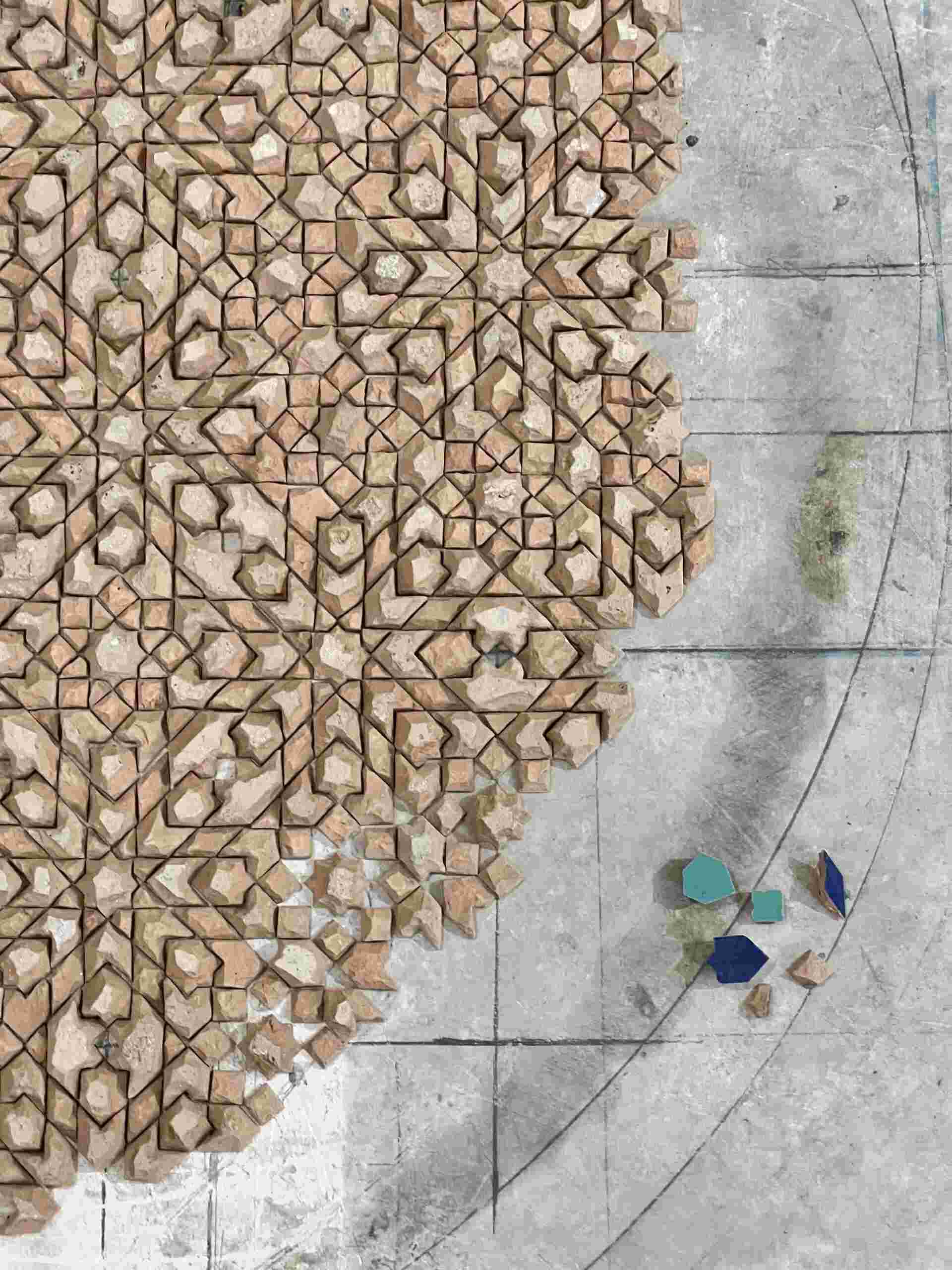

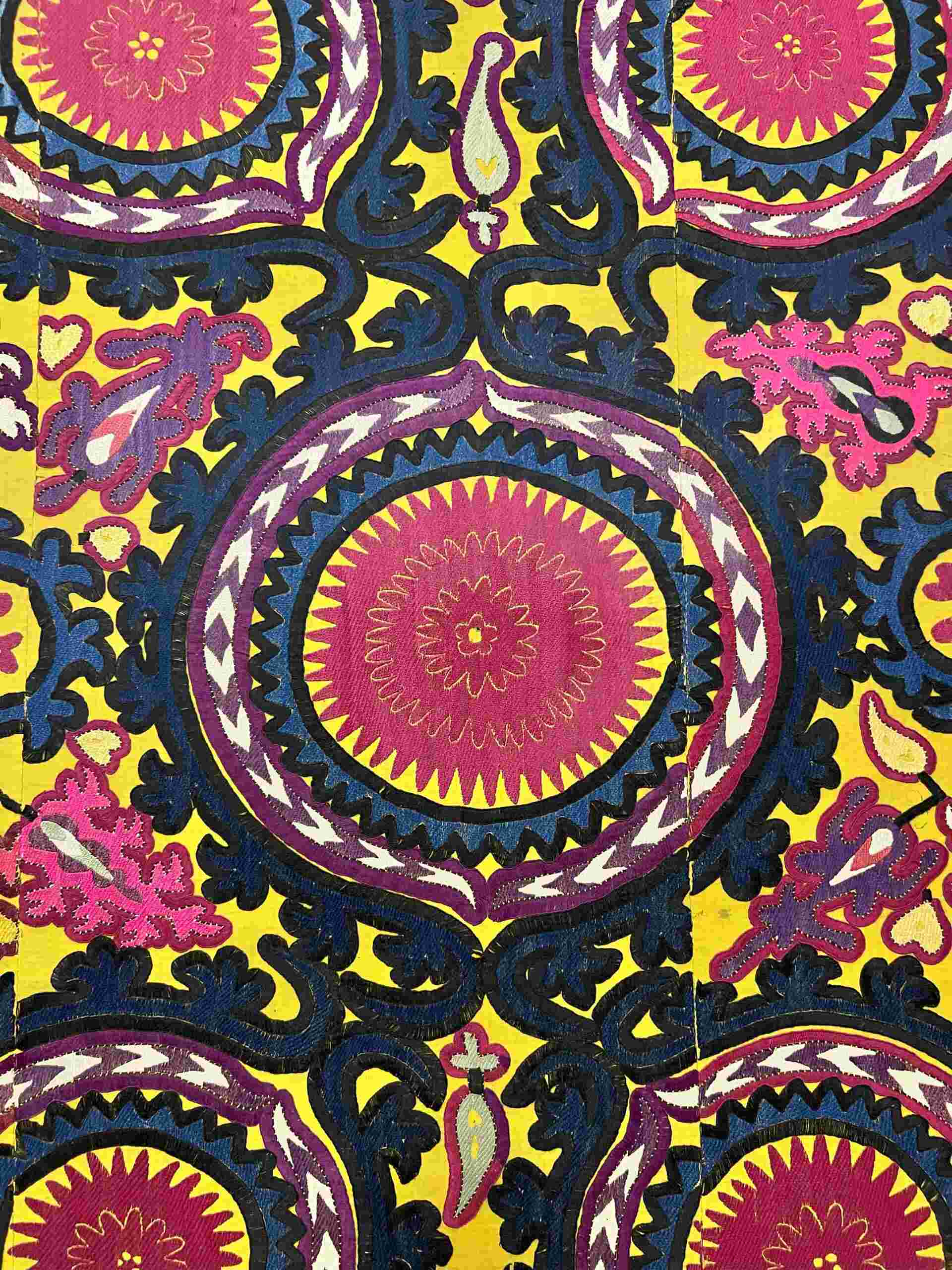

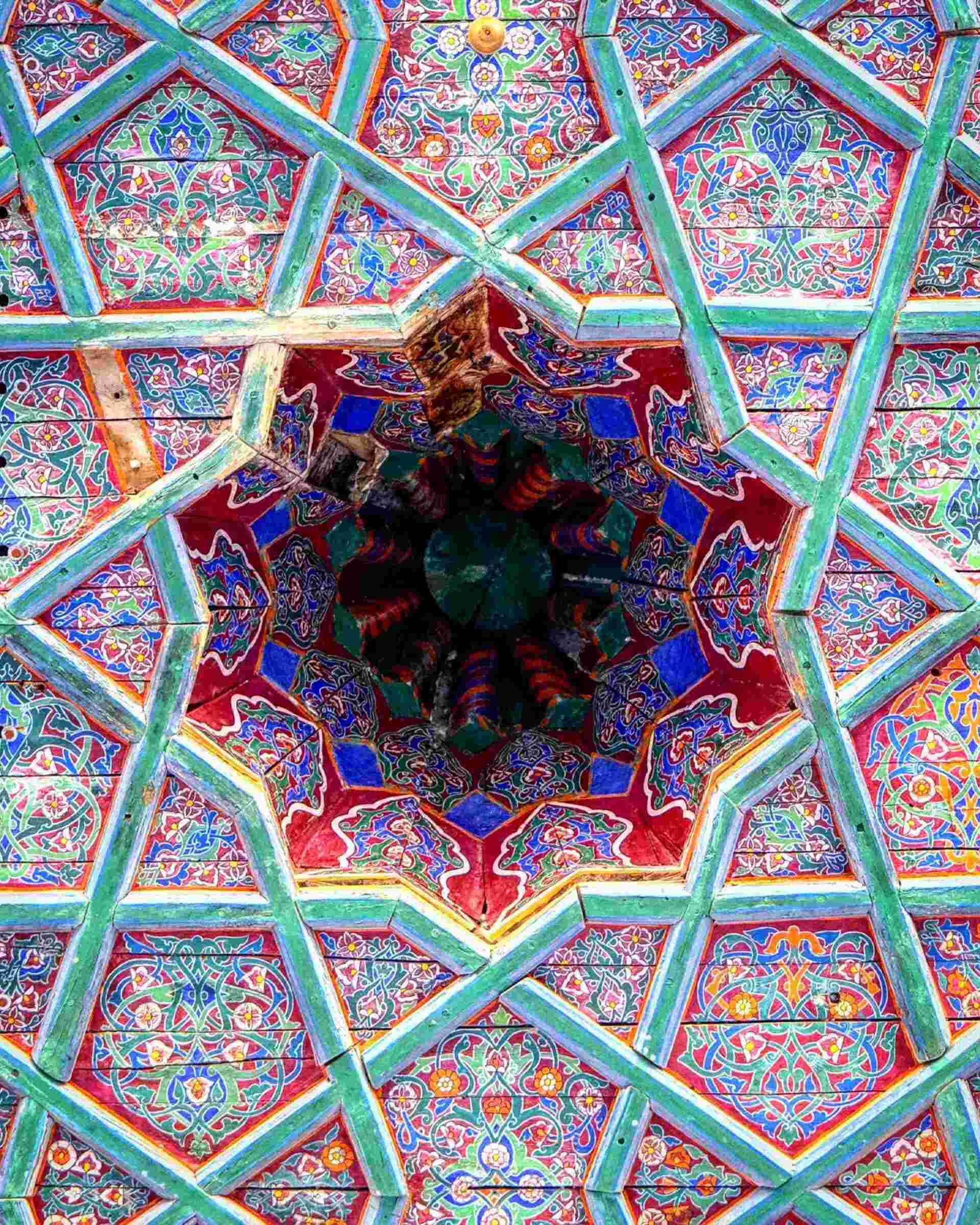

In 2022, Zahedi took a sabbatical year away from practising architecture and launched a 365-day field research project, a “longer journey of exploring,” which took her to 17 countries and more than 40 cities across major historic Islamic dynasties. The travels allowed her to connect with artisans and craftspeople in different locales (and connect them with one another), observe how styles and techniques repeat across regions or get locally inflected, and witness the complex geometries integrate into public spaces, for the enjoyment of all.

Safoura Zahedi’s travels took her to 17 countries (documented on Instagram @365daysofgeometry.), including Morocco, Portugal, Spain, Egypt, Turkey, Uzbekistan, India, Thailand, Cambodia, Malaysia and Singapore, to observe patterns in architecture and across various craft disciplines.

Zahedi was able to interact with artisans at work, like this plaster carver in Fez, Morocco and see themes and variations on the geometries, like the muqarnas structure (below at centre, in Bukhara, Uzbekistan), in both palatial and public settings.

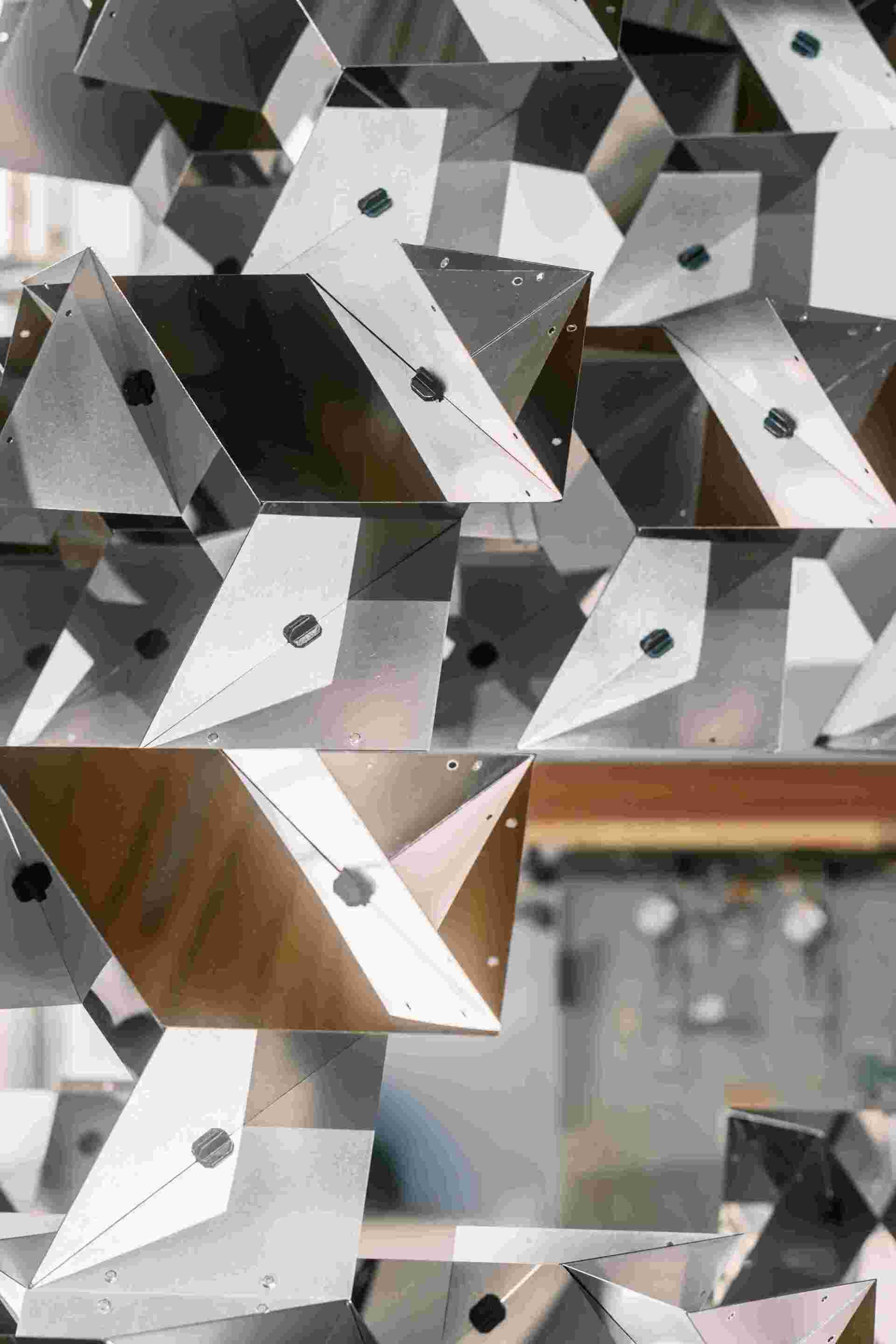

The pyramidal installation consists of just two elements: the steel fractals and 3D-printed connecting nodes. Much of Zahedi’s testing process was determining the correct ratio of weight to strength, “because we’re designing it to be stable in endless iterations.”

Photos by Kurtis Chen

Zahedi doesn’t consider the 3D patterning mere decoration or ornament, which, in accordance with a Western architectural education, would render it superfluous—or worse, elitist. By her advanced understanding, it is essential, facilitating contemplation, meditation and spirituality. “Geometrically complex spaces have mental and physical benefits” relevant to the contemporary urban context, Zahedi argues. Indeed, fractal or self-repeating patterns, commonly observed in nature—ocean waves or the branches of a tree—when integrated into built structures produce “some of the same effects as looking at nature,” she says.

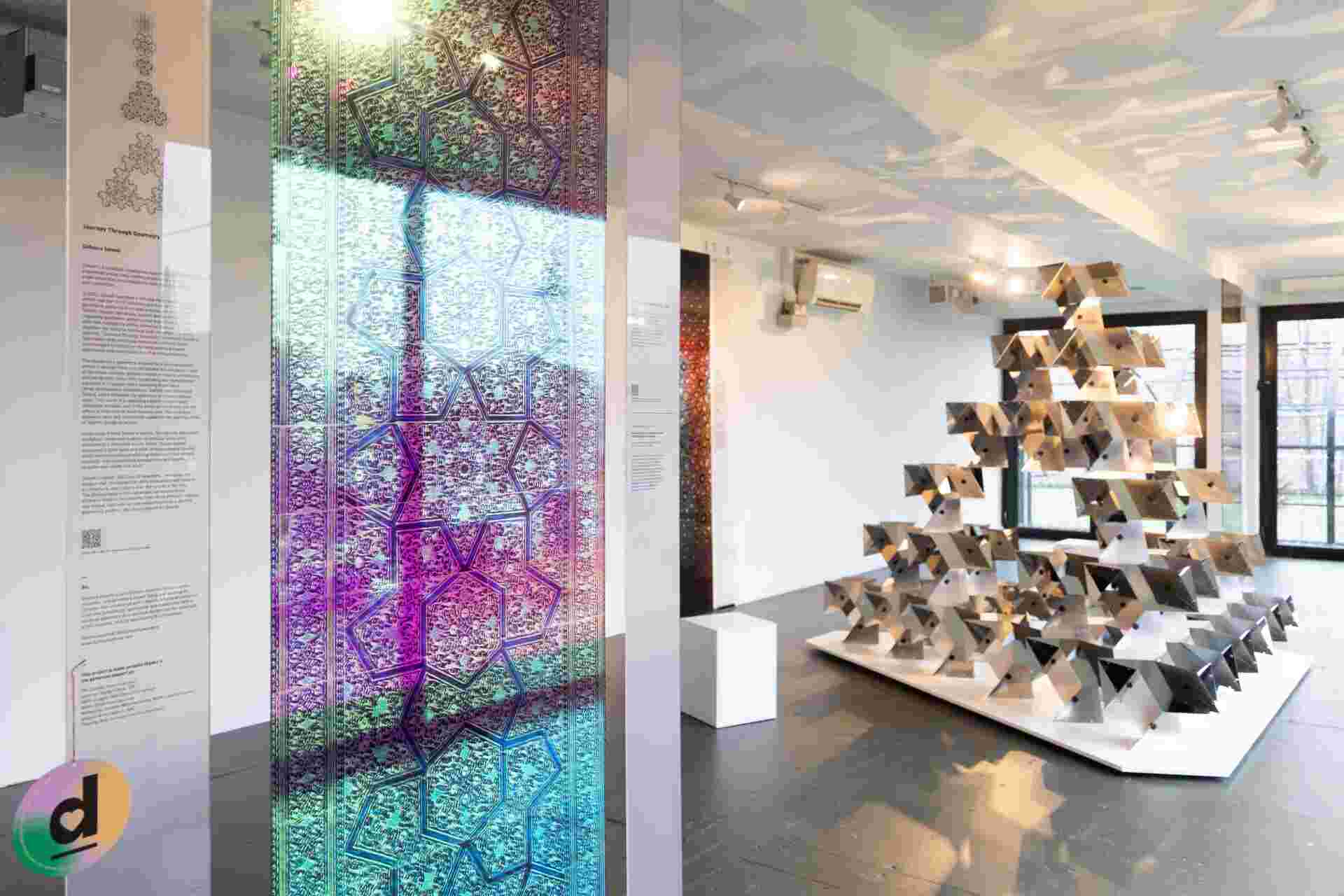

In returning to Toronto, Zahedi put her learnings into practice, creating a “fractalized installation” that debuted at the Interior Design Show, then went on to the DesignTO and Glisten festivals.

The exhibitions feature large-scale dichromatic prints of geometries witnessed in her travels, connecting the historic to the contemporary. “Why I love working with geometry is being able to open up conversations with people, and also between people who may otherwise not feel they have things they can connect on.”

Photo by Bruno Belli

The pyramidal structure consists of two essential elements: laser-cut steel shapes and 3D-printed connecting nodes, all flat-packable and reusable. The polished mirror finish extends the piece, infinitely. “Geometry as a visual language is about reflecting on how we’re all connected,” she says, revealing the spiritual in the mathematical. “Multiplicity within unity, unity within multiplicity; every part depends on the whole, and the whole depends on the parts.”

For Zahedi, this work and the entire ongoing pursuit—the research, travel, education (she’s creating an online course on Islamic geometry for The King’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts in London, England, and teaches at Toronto Metropolitan University)—is about connecting the dots between her ethnicity, spirituality and chosen path and profession.

“A huge part of it, for me, is bringing together these different parts of myself and wanting to connect to my own cultural heritage as a designer and an architect,” she says.

“It is me putting myself forward, as a whole person.”