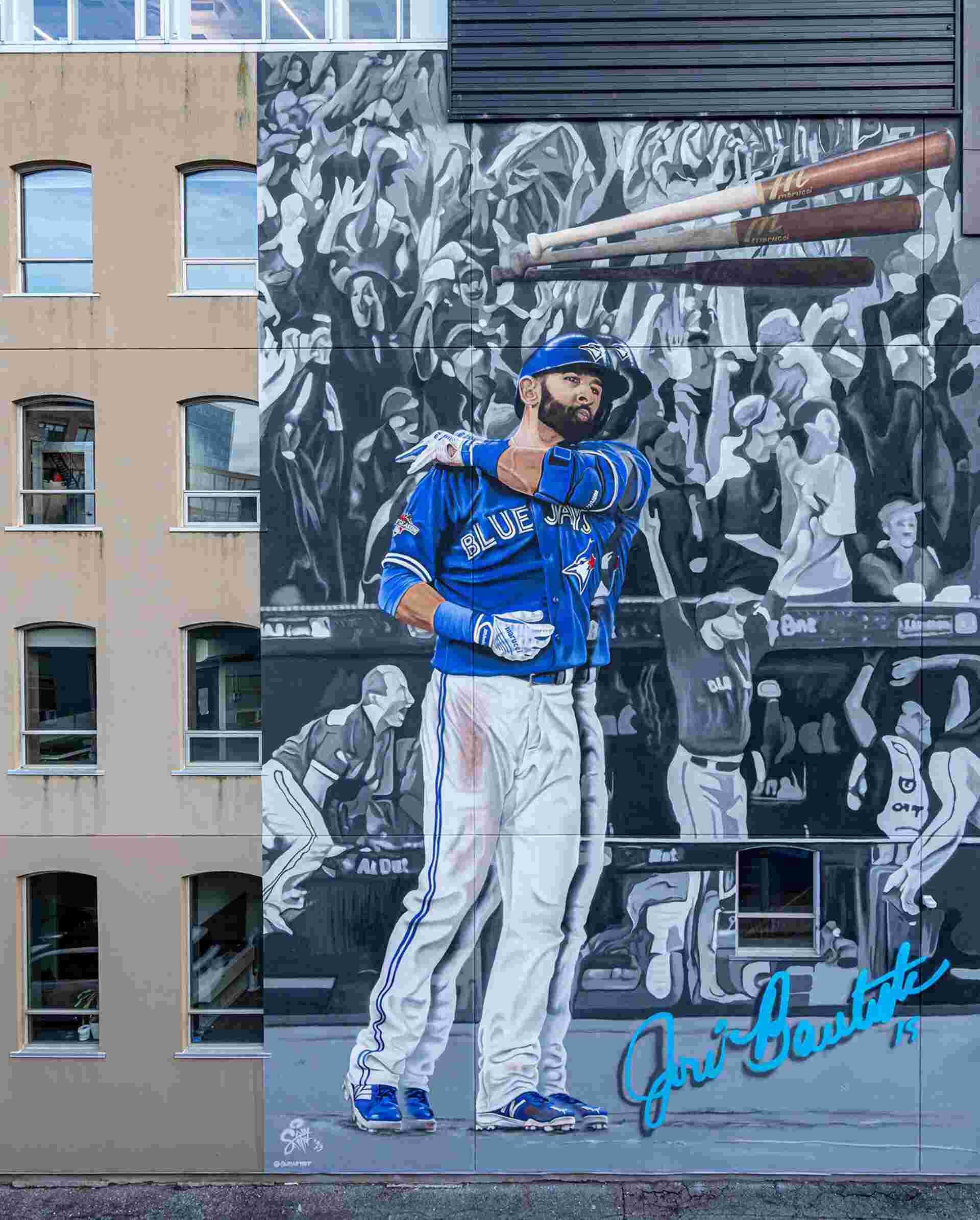

Freeze Frame

Make room for the arts Sum Artist’s José Bautista mural at 99 Spadina.

By: YVONNE GAVAN

Illustration By: Jason Logan

“You know, if it wasn’t for the sewer smell, I’d quite like it here,” I told my friend as we walked through a tree-lined lake park in our neighbourhood one afternoon. But secretly, there was a whole list of things I’d mentally labelled as “don’t like” that day, including the mosquitos and the intense humidity.

We were in one of the city’s most desirable areas, in a much coveted and rare green space. But I was finding it hard to witness beauty there. Not only on that particular day, but most days since moving to the chaos of Dhaka, the vastly overcrowded capital of Bangladesh, a few months earlier.

I told myself that I needed beauty in my surroundings to feel happy, calm and balanced; thinking of the stunning Regency architecture in our north London neighbourhood, or the view of jagged hills when we’d lived in rural southern Africa.

That weekend, during an online meditation retreat, I was introduced to a simple concept that intrigued. “Feeling tone,” I was taught, is the gut reaction we have to an experience, either pleasant, unpleasant or neutral. A direct translation of the Pali word Vedana, it’s a way to gain insight into how we experience the world.

Over the next few weeks, I tried to notice this process of labelling, and the more I registered my biases, the less offended I was and the more expansive my experiences became.

Walking by the lake, I’d look up, mesmerized by the pattern of leaves and vines that sheltered me from the sun. I enjoyed the feel of cool air on my face as I bumped along in a rickshaw, watching parakeets deftly swoop between spindly palms. Above the bustle of people and traffic, there was something strangely still and beautiful about the marbled surface of the moon that hung on the concrete edge of an unfinished building. It seemed to articulate something familiar yet entirely

new that I was feeling. And it wasn’t just me.

“You’ve got to see these,” my husband excitedly told me, swiping through images of woodblock prints by a Bangladeshi artist on his phone. What seemed at first like a mess of abstract lines turned out to be a series of close studies of Dhaka’s construction sites. Tangled wires and scaffolding as complex and intricate as fractals.

The city’s inhabitants understood what I had started feeling—they felt it too. “Unexpected beauty” was how the craft vendor described cloth bags printed with images of the battered and rusted blue sides of Dhaka’s buses that he was selling.

“Something’s changed,” I told my friend. “Dhaka’s different.” This time we were facing each other in a café, eating shingara from a paper bag. “I don’t believe it’s Dhaka that’s changed,” she said, gently tearing the hot pastry apart. “It’s you.”