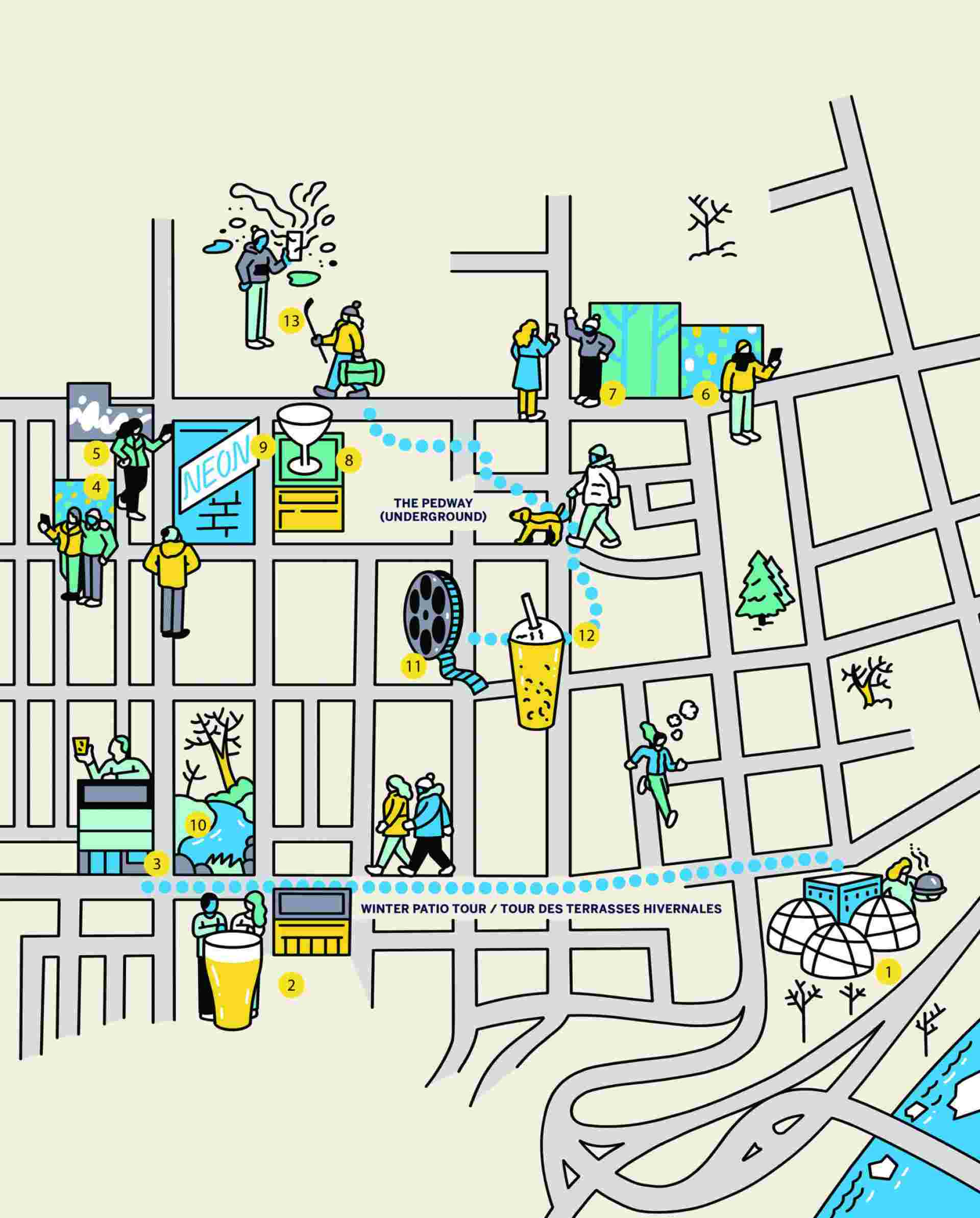

10310 102 Ave.

The 1KM Guide Icy cocktails and more wintery fun in downtown Edmonton.

Umbereen Inayet in Marie Curtis Park, Etobicoke, the location for New Monuments.

By Sarah Liss

Photos by Jalani Morgan

Midway through 2021, grappling with the claustrophobia and monotony of riding out COVID’s third wave, Umbereen Inayet escaped her hometown of Toronto and fled to Banff. For most of us, a mountain getaway holds a certain restorative appeal; for Inayet, the experience was a revelation. “As soon as I saw those mountains, I was humbled. It was a huge reminder that we haven’t seen it all. There’s so much more to do, so many mountains to climb. I’m a tiny speck in the wheel of existence,” she says. “I felt like it fed my soul in a way my soul hadn’t been fed for a while because I’d been focusing a lot on problem-solving. As I’ve filled my cup through culture, it’s been more about asking how we can hold space for pain. This was really about holding space for joy.”

That’s not to say Inayet hasn’t found some measure of euphoria via her creative pursuits. Since 2008, when she joined Nuit Blanche as an artistic producer, the interdisciplinary visionary has been working to transform urban landscapes through public art. Inayet has made magic with festivals, independent plays and digital media. She’s been a spokesperson at conferences dedicated to change through innovation. She’s enacted multi-tentacled interventions in parks and public squares. And she’s collaborated with A-list creators to amplify voices outside the mainstream. But, as she notes, the work she does is not simple escapism.

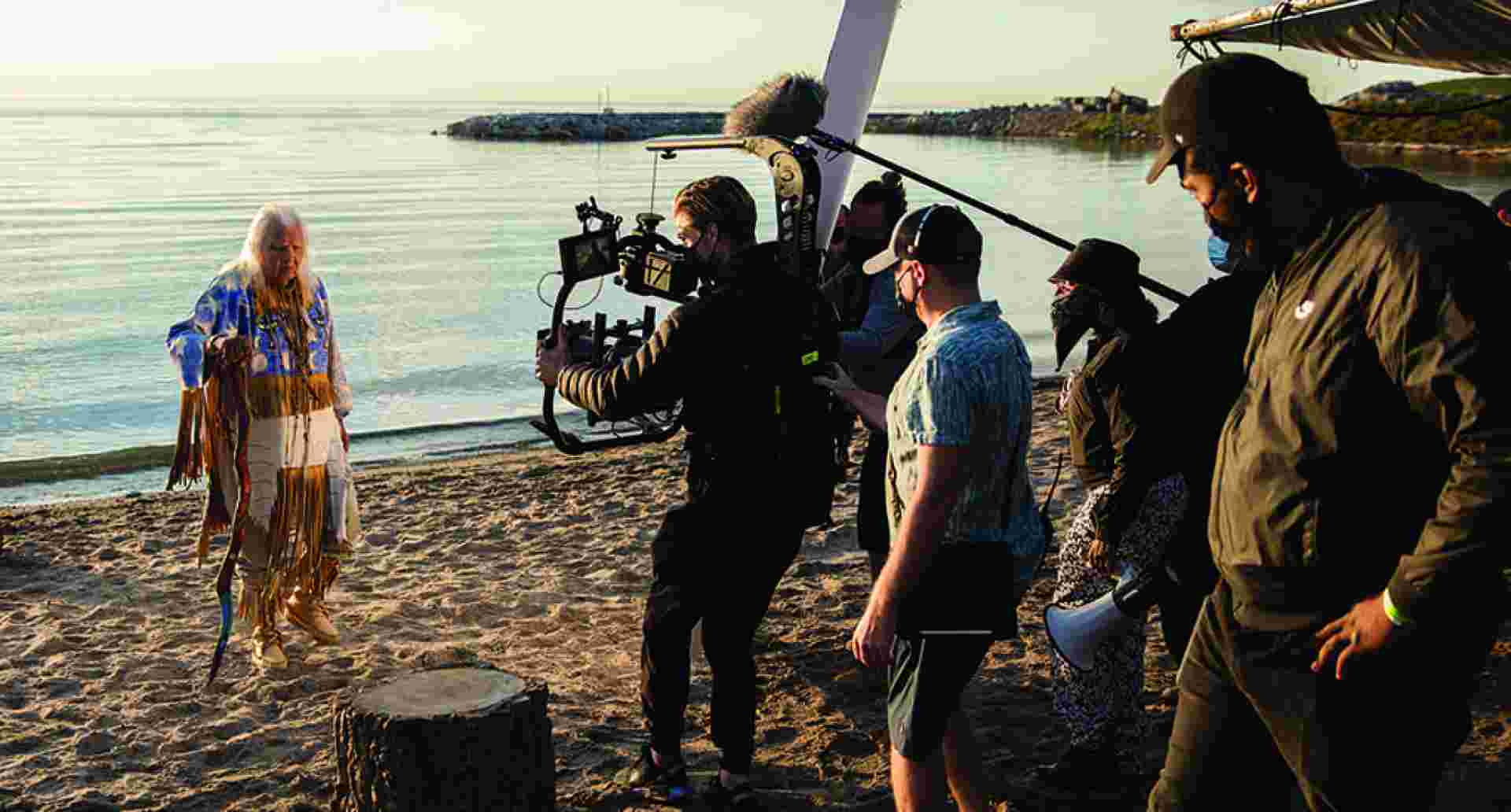

Umbereen Inayet in Marie Curtis Park, Etobicoke, the location for New Monuments.

Photos by Jeremy Mimnagh

That ethos is also at the heart of New Monuments, a stunning performance-based collaboration between Inayet and Canadian-born, internationally renowned Director X (a.k.a., Julien Christian Lutz). Inayet explains that the work reveals the legacy of colonialism and the collateral damage of nation-building by weaving together the frayed threads that are often left out of the story of how Canada (or Turtle Island) came to be. Apropos for a piece that shines light on the Black, brown and Asian bodies that literally built (or were sacrificed in the project of building) this country, New Monuments tells its story through bodies in motion—specifically, the bodies of more than 30 dancers from a host of different groups in Toronto.

The project was originally conceived as a kind of interactive intervention on Yonge Street (the longest street in Canada) and slated to take place in the summer of 2021, but COVID reconfigured the plan. Meanwhile, statues representing old-guard history’s victors were being overturned by activists around the world. The fallen icons were a literal representation of Inayet and X’s central metaphor of upending the dominant narrative. Immersed in discussions about treaties and stolen land, Inayet and her collaborators developed a new and profound sense of the role landscape plays in the ideas they were hoping to highlight. So, in October 2021, they brought together their performers—artists working in styles from hip hop to ballet to tap to Indigenous hoop dancing—overseen by noted choreographer Tanisha Scott, to carve out an overlapping narrative in motion set in Marie Curtis Park in Etobicoke, Toronto, on the shores of Lake Ontario.

The New Monuments performance featured over 40 IBPOC dancers from ten dance companies, telling the stories of Turtle Island’s Indigenous peoples, Chinese railway workers, enslaved African Americans and more.

Inayet approaches each project with a distinctive combination of empathy, insight and ambition informed as much by her academic background (she majored in anthropology and women’s studies and completed a master’s in social work) as by her personal and professional experiences: She’s a racialized female-identifying child of immigrants; she’s a social worker who’s spent no small amount of time engaging with people who’ve undergone profound trauma. Her Awakenings project, launched in early 2021 with Toronto History Museums, mobilized IBPOC creators to produce interactive work—from musical performances to short films—illuminating the vital narratives that remain untold while dominant histories are enshrined by institutional discourse.

“Changing the gaze is really important for me,” she says.

“I spent six months looking for these hidden truths—the stuff we don’t talk about: the corsets women were forced to wear, the queer people who weren’t allowed to love. I think it’s our responsibility to dig out those stories for the people in the museums and to give them something creative to respond to.”

“Movement represents freedom,” says Inayet. For her, that freedom is also about feeling empowered to not just exist but also be a dominant force in the world of contemporary art—an environment that she found deeply alienating when she first started doing this work. She says that as a kid, she didn’t really visit galleries or museums. “Honestly, I thought art was for rich white people. My dad would take photos and my parents sang songs with other people, but those were things you did at home when you came back from your factory job.” Even so, she always had a latent sense of the power art could hold as a therapeutic tool and a collective force. Her great-grandfather, Hafeez Jalandhari, wrote Pakistan’s national anthem. When Inayet reflects on that, she’s caught up in the idea of “something bigger than [her] that connects a country, that unifies people.”

“That’s how I think about public art,” she says. “How can it serve? How can it hold a space for emotions? How can it bring people together who may not be coming together?”

A portrait of Mary Ann Shadd, the American- Canadian abolitionist and the first Black woman in North America to publish a newspaper, The Provincial Freeman, created by artist Yung Yemi as part of Inayet’s Awakenings project for Toronto History Museums

Photo by Andrew Williamson, ‘Yung Yemi’.