342 Water Street

They call it Gastown: 342 Water Street and environs

BY: Dori Tunstall and Peter Morin

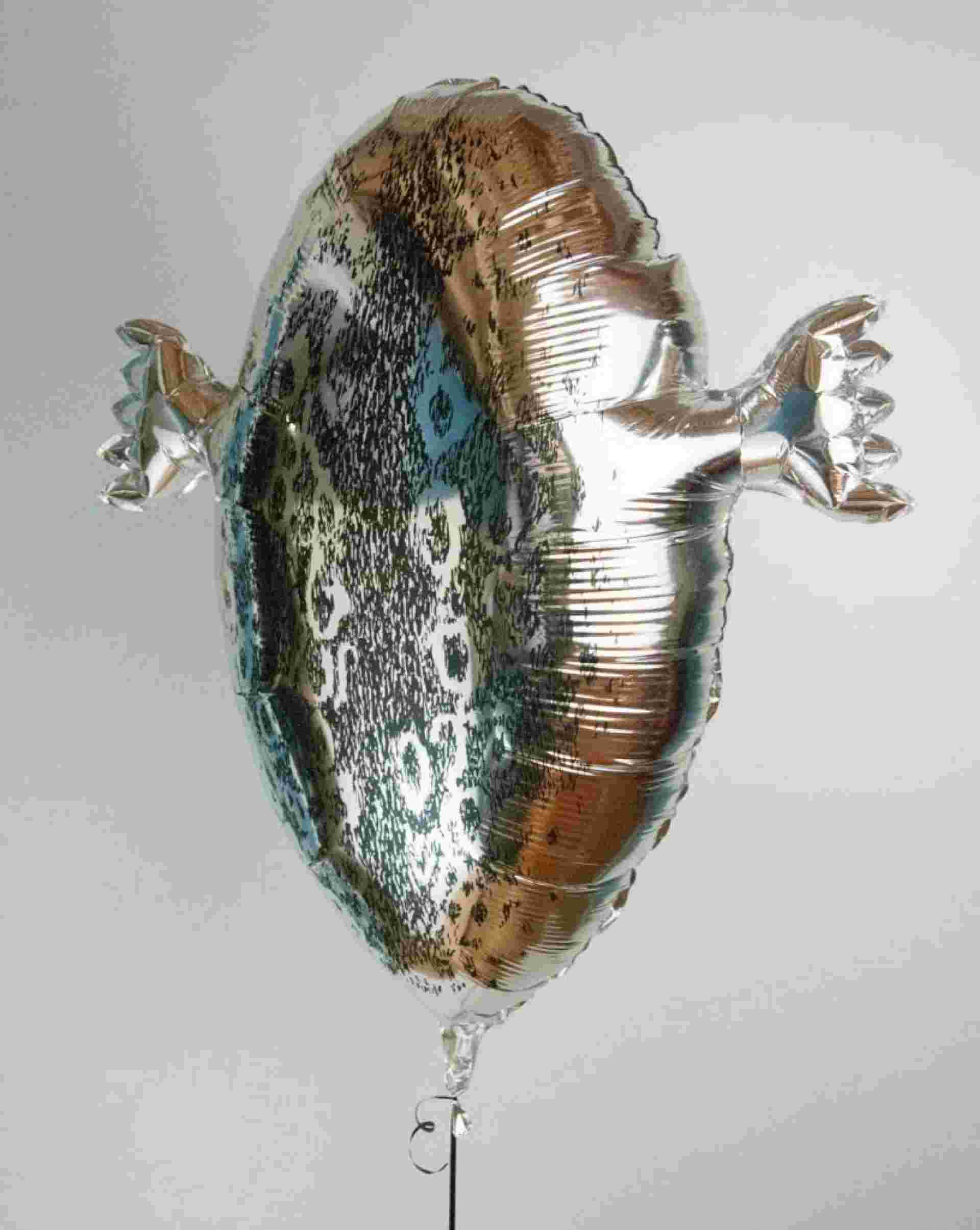

ART BY: Couzyn Van Heuvelen, Avataq (2016)

Dori Tunstall: The question we’ve been asked to discuss is: What is decolonizing design? But first we must unpack what decolonization is, and I think that conversation is led by those who are Indigenous.

Peter Morin: Decolonization is about power, right? And it’s an acknowledgement of how certain white folks have built and maintained a system that enables them to keep themselves drowning in that power. When I work with students, community members and elders, I have to explain colonization before we can even start talking about decolonization. My working definition of colonization is: Colonization is the forced removal of resources from Indigenous territories. Resources are not singularly tied to what’s under the ground or on the ground. Resources include the land itself, intellectual property of Indigenous people, intellectual production, artwork and our bodies.

That’s such a rich definition. It opens up so many nuanced possibilities around a holistic understanding of what the colonial project does and has done.

In the work that I used to do, I needed to be able to say to an elder or a youth, “This is what colonization is.” Back home, folks are using that word to describe a lifetime of experiences and also trying to understand [that term] so that they can stop apologizing for feeling powerless. Decolonization becomes an active interrogation and a dismantling of the privileges and powers that you receive as a result of colonization. And how to activate a decolonizing methodology is something you have to determine for yourselves. But keep in mind: If it doesn’t hurt, then you’re not doing it right.

The discourse of decolonization from my Black American perspective comes out of the liberation struggles in Africa and then, to a certain extent, the Caribbean as well. We often forget the deep interrelationships between the Caribbean and Africa. But that means that notion of decolonization is more centred in the body than it is in a sense of land. There are similar experiences of displacement from the land, but it’s complicated by the fact that we can’t go back to the land. The “motherland” rejects you.

Well, the land can kill you or welcome you. It is always complicated.

I’ve always gravitated to design because design has been the communication of ideas through adornment for at least 65,000 years. To me, decolonizing design is about getting to the point where making, as it relates to our bodies and adornment, brings liberation.

I’m thinking a little about how decolonizing design can also mean that we design the object, make it and give it to somebody to use. In thinking about what you’re saying, decolonizing design also enables liberation for the community. The sharing of the object makes us free. I feel like I need to put on my grandpa’s hat for the rest of our visit.

I’m channelling my great-grandmother’s hat.

When we think about decolonization, what we’re also trying to do is understand how potent and expansive the knowledge of Indigenous and Black and folks of colour actually is. It goes beyond the containers. These knowledges are joy and celebration, and they help you to see your family better. This competes with colonial power. Like racism, colonial power is very slippery. It took me 42 years of life to realize that when I’m using that word “racism,” I’m actually reporting how your behaviour is causing me pain.

There’s something about the trauma that Europeans have experienced in Europe. So if we want to understand why racism and colonization is happening, we might just start with Dickens. Dickens describes the way in which the European poor were made into criminals for being poor. Then they were shipped to Australia and to Canada; they became soldiers in India. And so for me, why does racism persist? I feel that many white people have not dealt with their own intergenerational trauma. But what I love about what’s happening in various Indigenous communities around the decolonization of design, and I frame this really very carefully, is that the communities are feeling safe enough to uncover their hidden knowledges of making.

I just believe so strongly in the inherent power of our respective knowledges, and that also includes grandmas, not just nations. Grandmas have that power. They are also a part of the making team. (The making team is an acknowledgement that your making is informed by a history of artists, thinkers and makers.) And also, your making is connected to a future of makers who have yet to contribute to the art and design history. My own making team includes folks like Audre Lorde—her quote “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” When I’m making, I think, “What is the tool from the design history of the Tahltan Nation?” Audre’s knowledge becomes part of the making of that new tool, which then becomes a stronger thing. Then I have to dream in order to activate that tool. I don’t think that Audre’s saying we—Indigenous, Black and people of colour—don’t have tools and don’t have the skills to use those tools. She is saying that some of the master’s tools are bent, and we have to stop being attracted to these bent and broken tools.

There’s something very optimistic about how we might recognize all the nuances of our various identities, which were lost or hidden, and celebrate them without hierarchy. A lot of damage has been done by the systems of hierarchy that say that “this” is better than “that.”

It gets complicated for Indigenous folks. I’m speaking with this body and using the word “appropriation,” which [we’ve experienced] at times as outright theft. But then you come from a deep history of sharing knowledge as a priority. We’re community members. You share with me and I share back with you to honour the gifts of your sharing with me.

This is where I think the problem with appropriation and misappropriation is actually the stopping of the free flow. They say, “This is mine and I’m going to exploit this without being in dialogue with you.”

It’s about how we meet each other with love, kindness, care and grace, which are part of our cultures. It is also about how that well-made object is so powerful. The priority was to gather and trade for materials for the artists and the designers so that they could make new things for the community. This making and sharing of that object is joy, and until you start decolonizing your design thinking or design, you can’t see that joy or that love of making.

Joy brings us back to our discussion of the liberation of the body. I always think of joy as our expression of the ultimate freedom and connectivity to all things around us. And so to think that that could be embodied in an object is so powerful.

It’s so powerful. When you hold it, that object remembers how the joy flows into your body. And as a future maker, try to hold on to the actual objects made by your ancestors.