Hidden Kingdom

The Conversation On mushrooms, interdependence and artists’ role on the sustainability front.

By Emily Waugh

Photos by Derek Shapton

A self-described “nomad” in his early career, Burtynsky settled at 80 Spadina in 2002, in part to house his growing archive.

Edward Burtynsky sees the world differently—not just as an artist but because he spends up to three months of the year looking at it from hundreds of feet in the air. Using a helicopter, airplane or drone, he flies over restricted industrial sites and resource-extraction landscapes shooting photographs that, as he puts it, “pull the veil” off how these processes affect the earth.

“Even with a helicopter or fixed-wing [aircraft], it’s a bit of an art to getting what you want because you can never get back to that place,” he says, noting that he once tried a weather balloon, but it was a “full fail” because the balloon followed the wind instead of Burtynsky’s intuition.

When he’s back in the Toronto studio, his home base since 2002, he can most often be found at the almost floor-to-ceiling magnetic pin-up board where he marks up large-format prints, fine-tuning them for optimal viewing conditions, whether they’ll hang in a corporate office or private home or on a gallery wall.

Today, Burtynsky hovers over a different type of landscape—a sea of copies of his most recent book, African Studies, waiting to be signed. The collection is Burtynsky’s first look at the reach of globalism on the African continent and features photos of the otherworldly industrial landscapes we have come to associate with his work: inky black tailings from a diamond mine in South Africa and pink salt pans in Namibia.

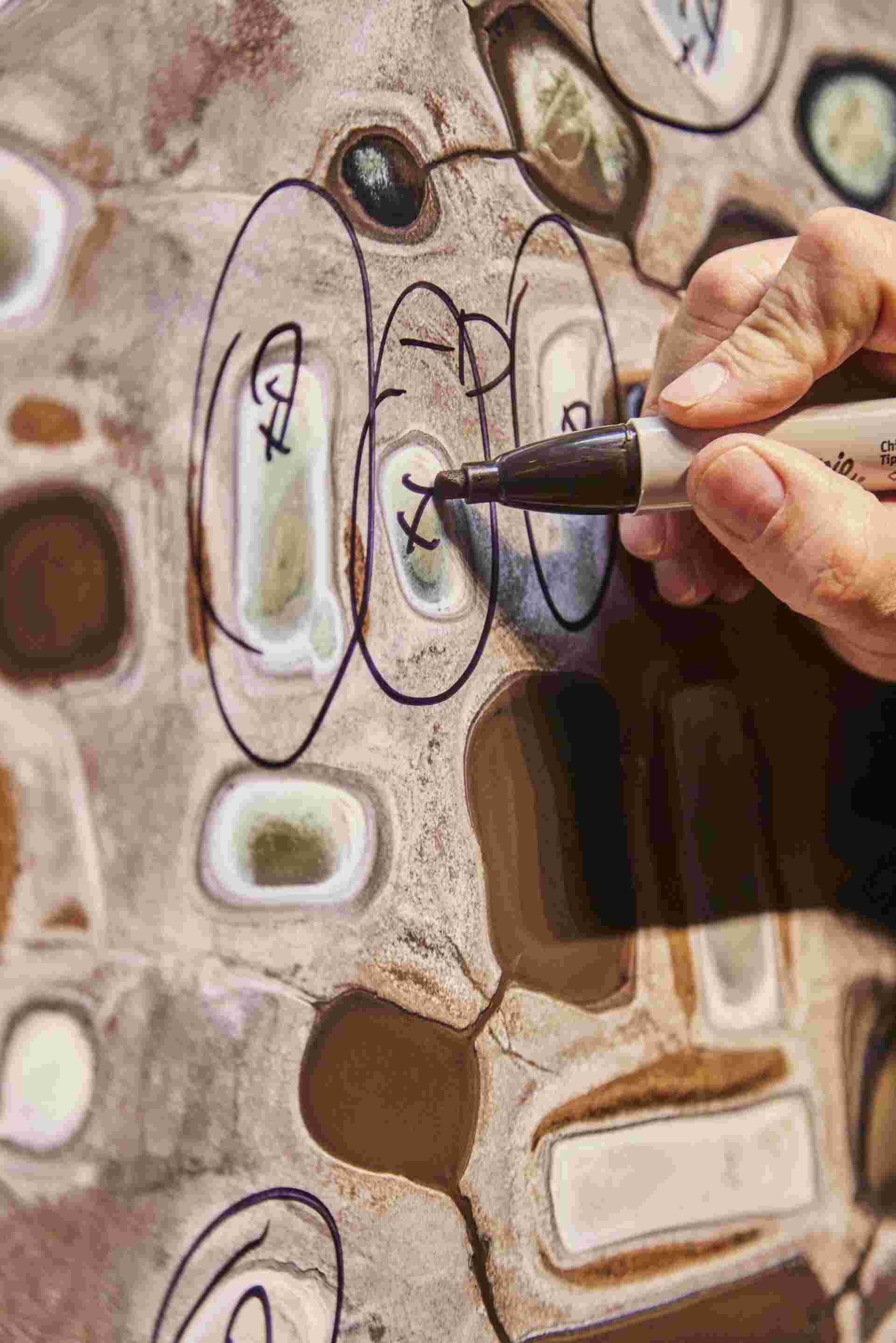

The artist uses a black Sharpie to mark up a print of a salt pond near Fatick, Senegal. Each photo is taken in what he says is “a fraction of a second.” The rest of the work is post-production.

Burtynsky reviews an image of a tailings pond at a diamond mine in South Africa under two different lighting systems: a daylight balance unit and a 3000K colour temperature LED to mimic traditional gallery settings.

It also highlights his more recent focus on the world’s remaining natural landscapes, including a mountain-like sand dune in the Namib desert and a “flamboyance” of flamingos on the shore of Kenya’s Lake Bogoria.

After what Burtynsky calls his “40-year lament on the loss of the natural world,” he now depicts these intact natural systems as a reminder that they are still worth fighting for.

“The problem is so big and so frightening that there is a danger of paralysis,” he says. “It’s incumbent on us to make sure that it doesn’t feel hopeless.” With his camera, Burtynsky opens that window of hope.