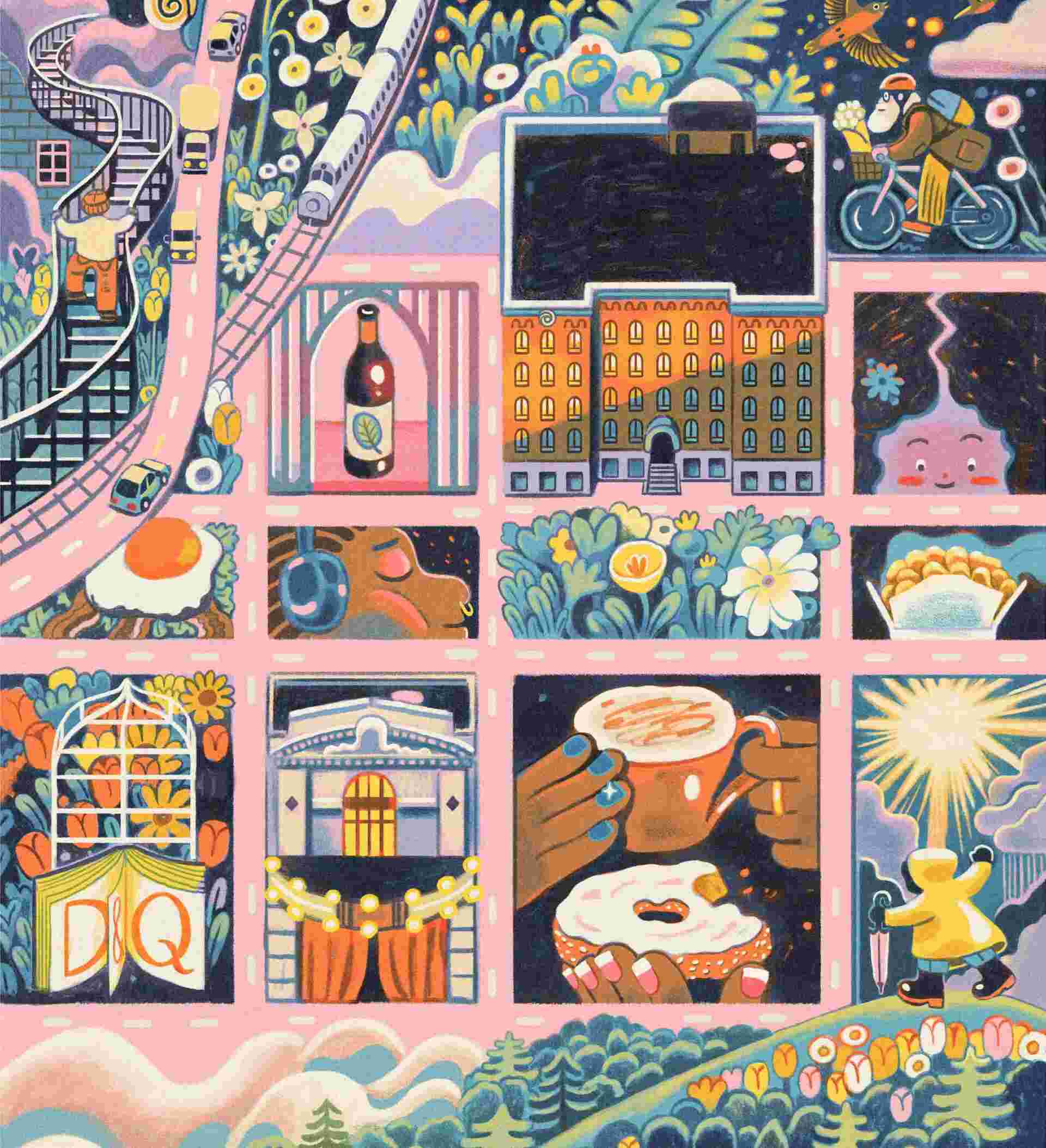

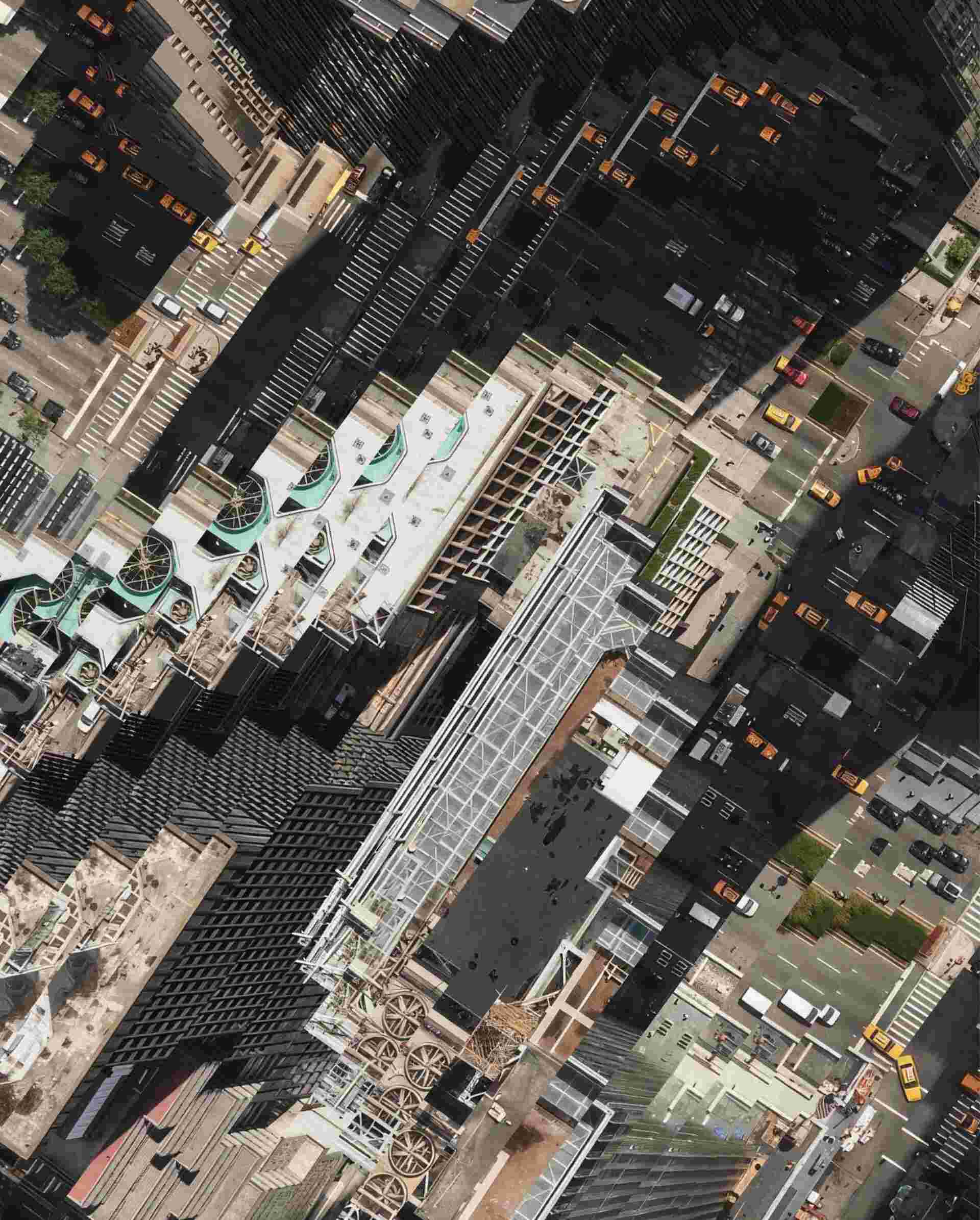

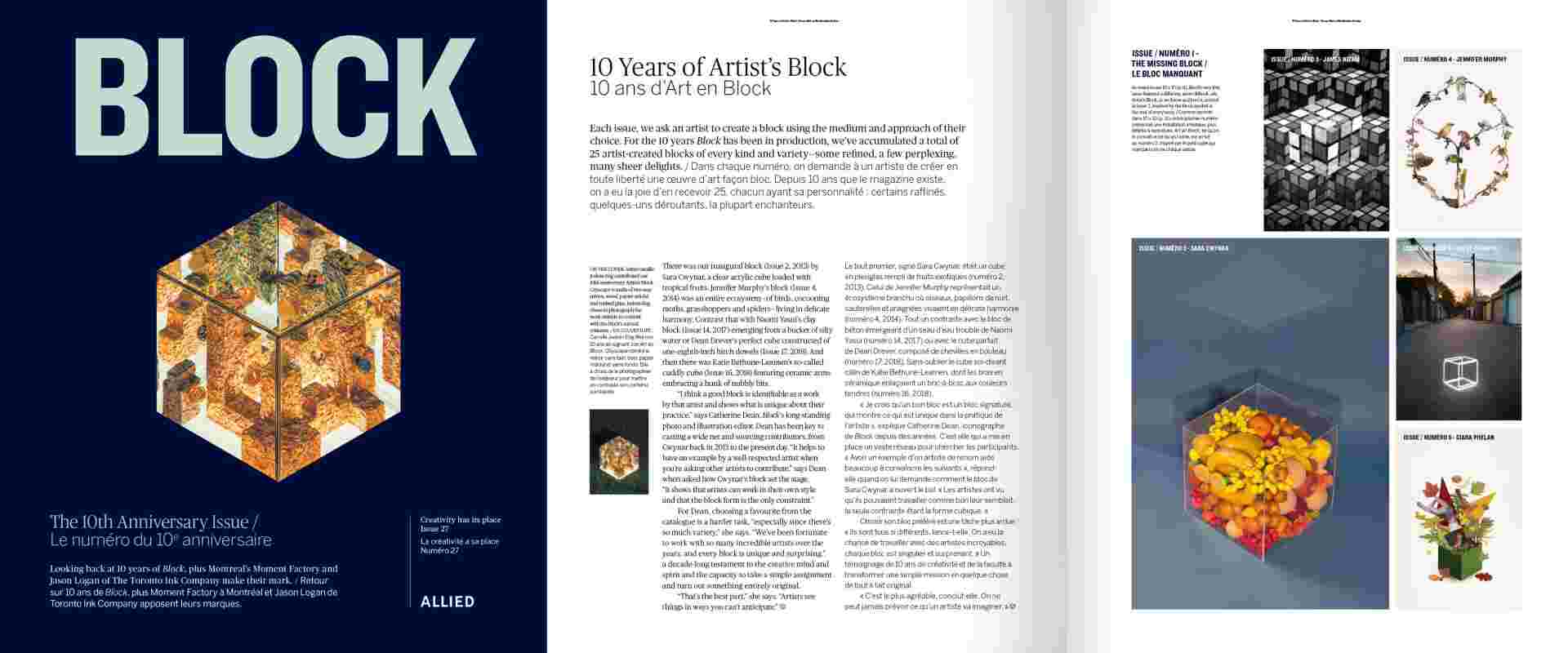

10 x 10

10x10 A not-comprehensive list of highlights from the past 10 years of Block.

10x10 A not-comprehensive list of highlights from the past 10 years of Block.

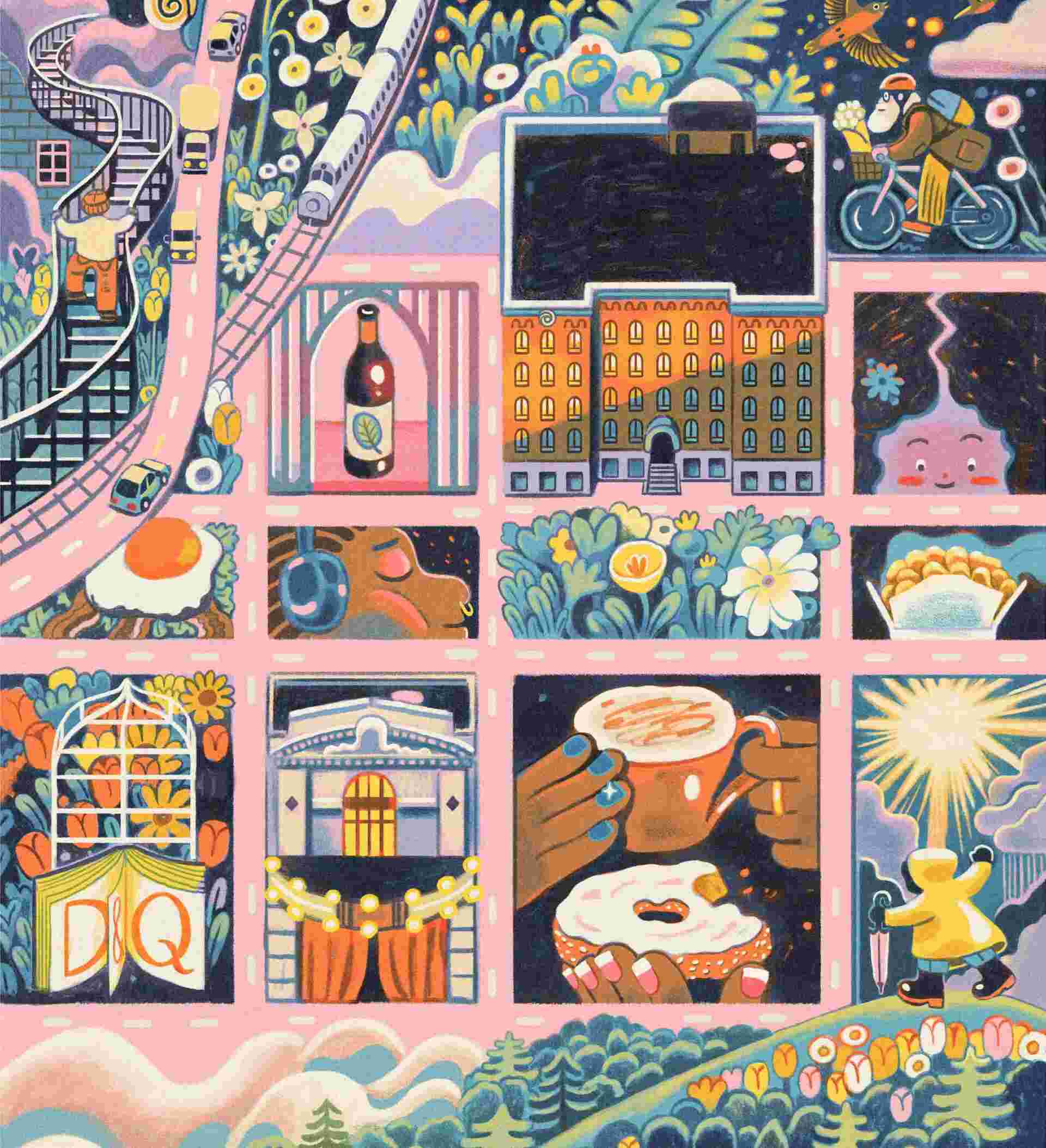

Artist’s Block Each issue, we ask an artist to create a block using the medium and approach of their choice.

The Moment Cheryl Catterall is all smiles, her hand movements agile as she ties the laces of her steel-toe boots and her eyes deliberate as they meet the large construction site before her.

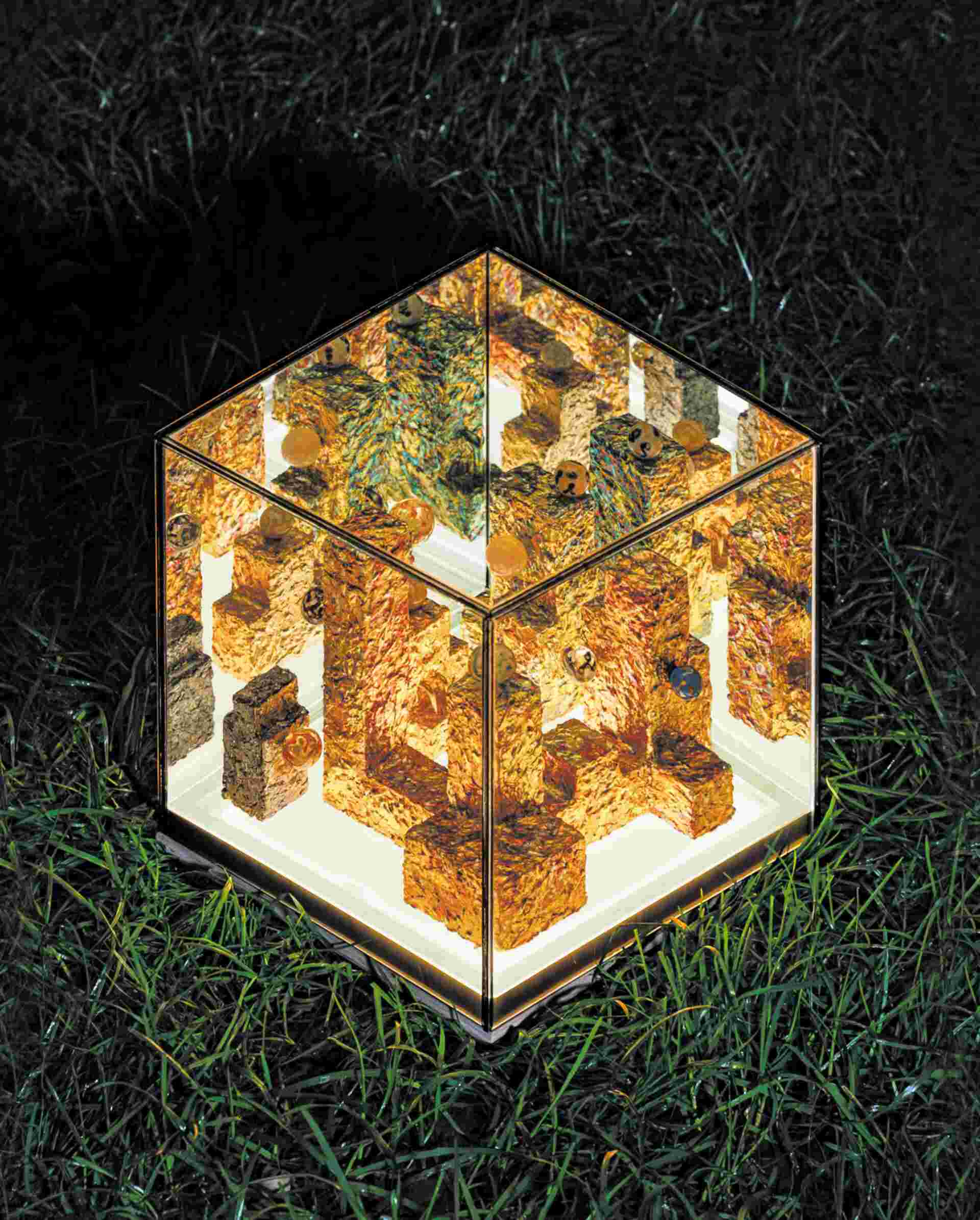

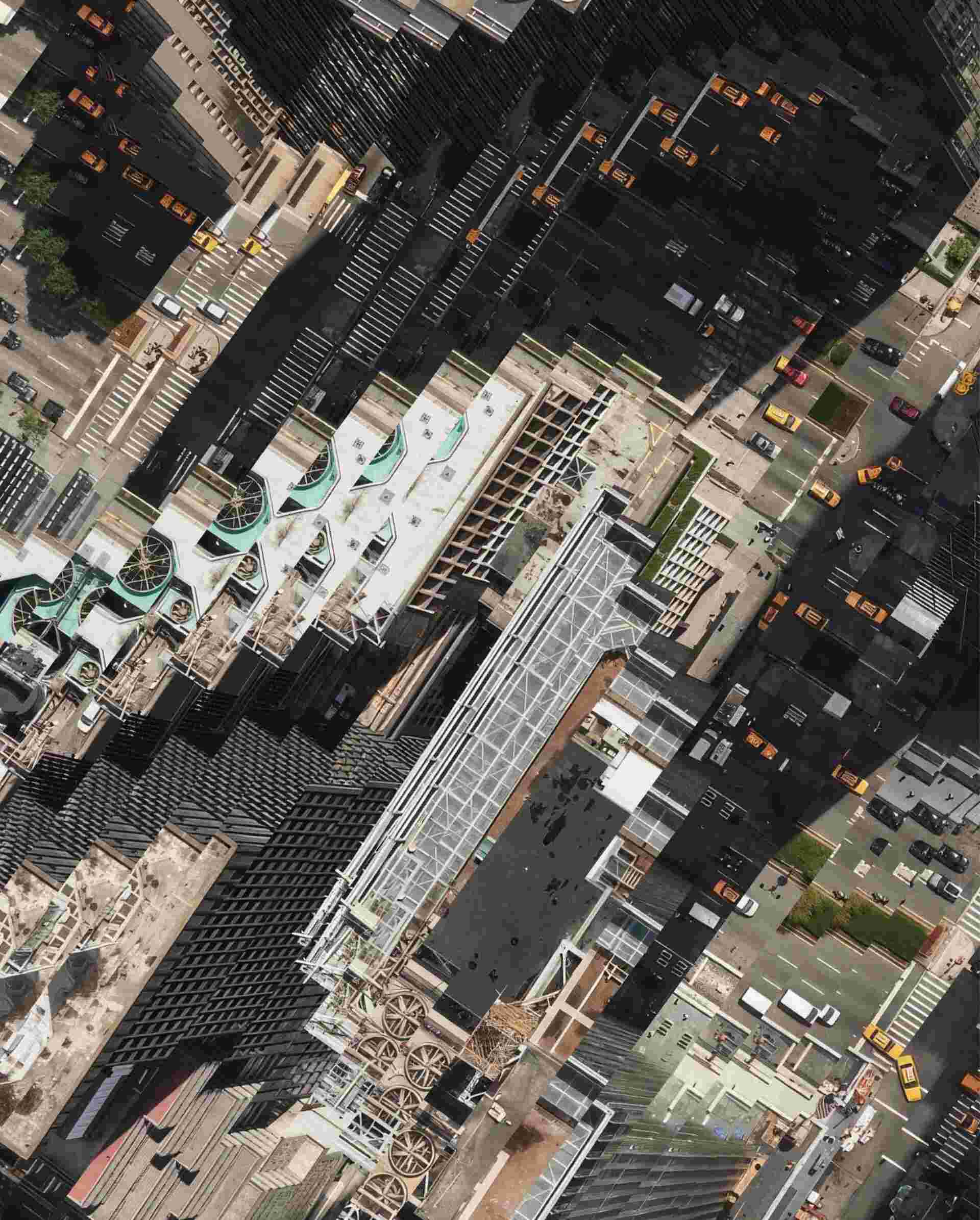

Fill In The Blank Katherine Lam’s urban infill.

The Conversation In an endeavour she calls “food rescue,” Lourdes Juan, an urban planner and the founder of Calgary-based Hive Developments, launched a tech start-up called Knead

Rethink People in the city always want to move. To a bigger apartment. To a house with a yard. Downtown. Uptown. Or out of the city entirely.

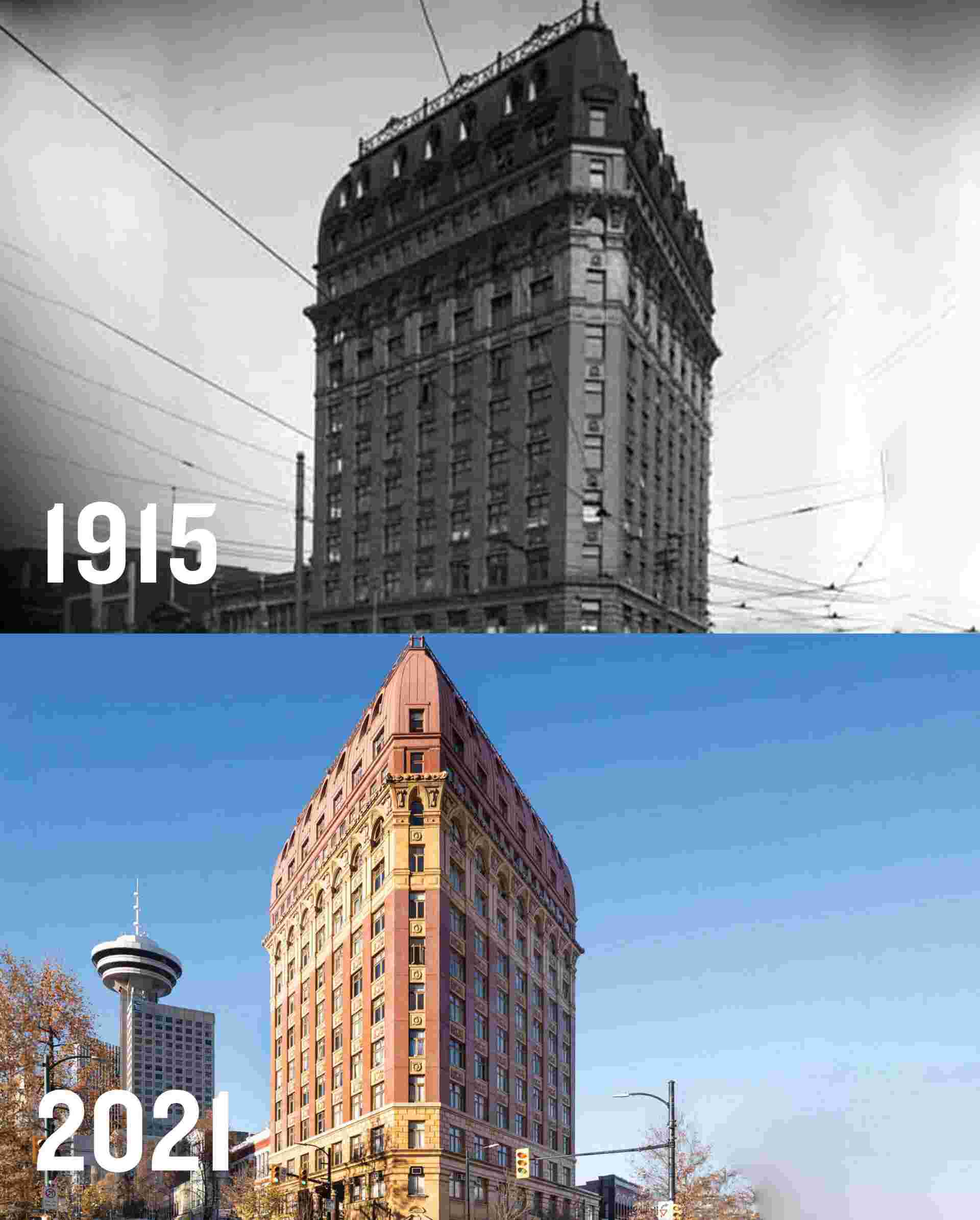

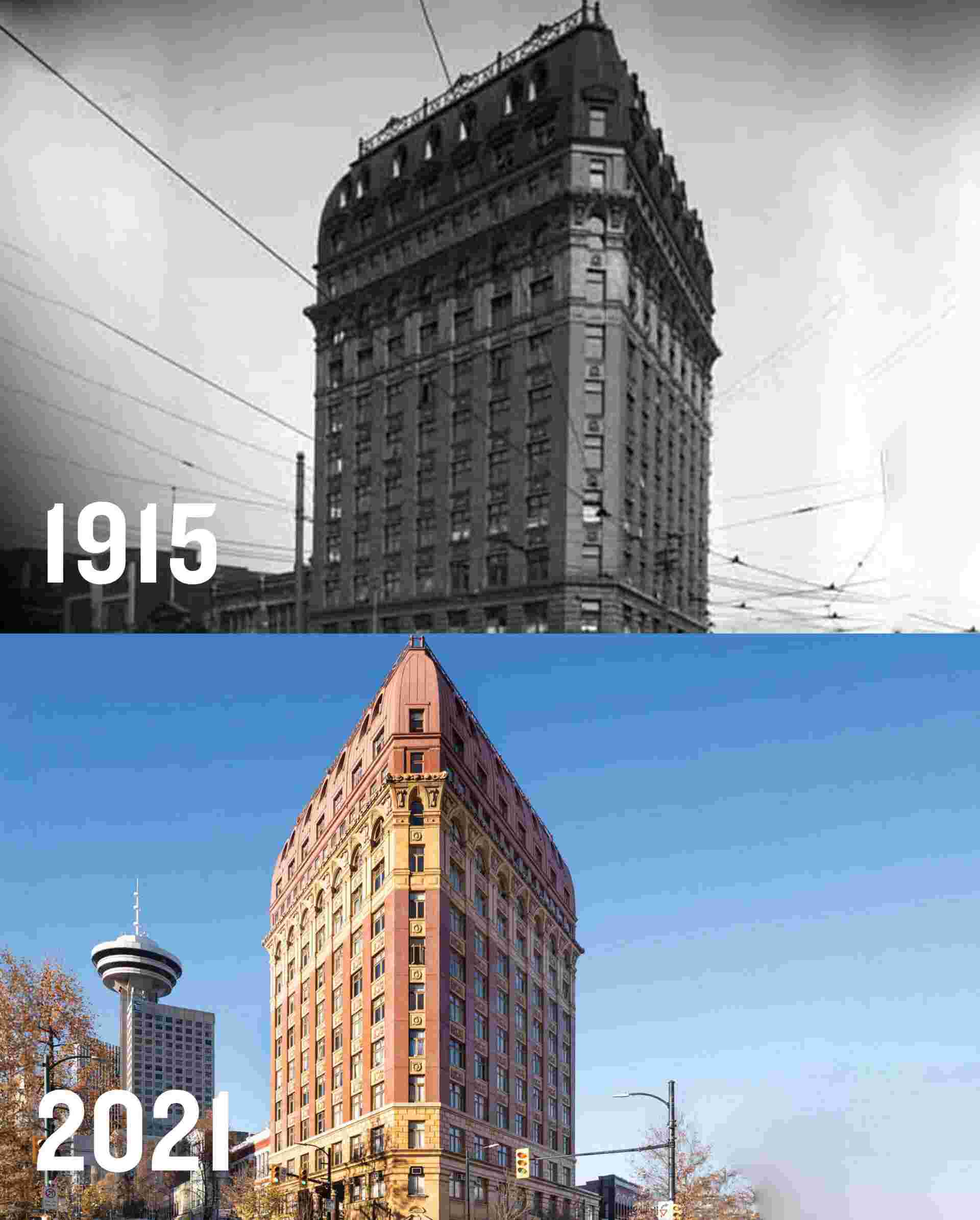

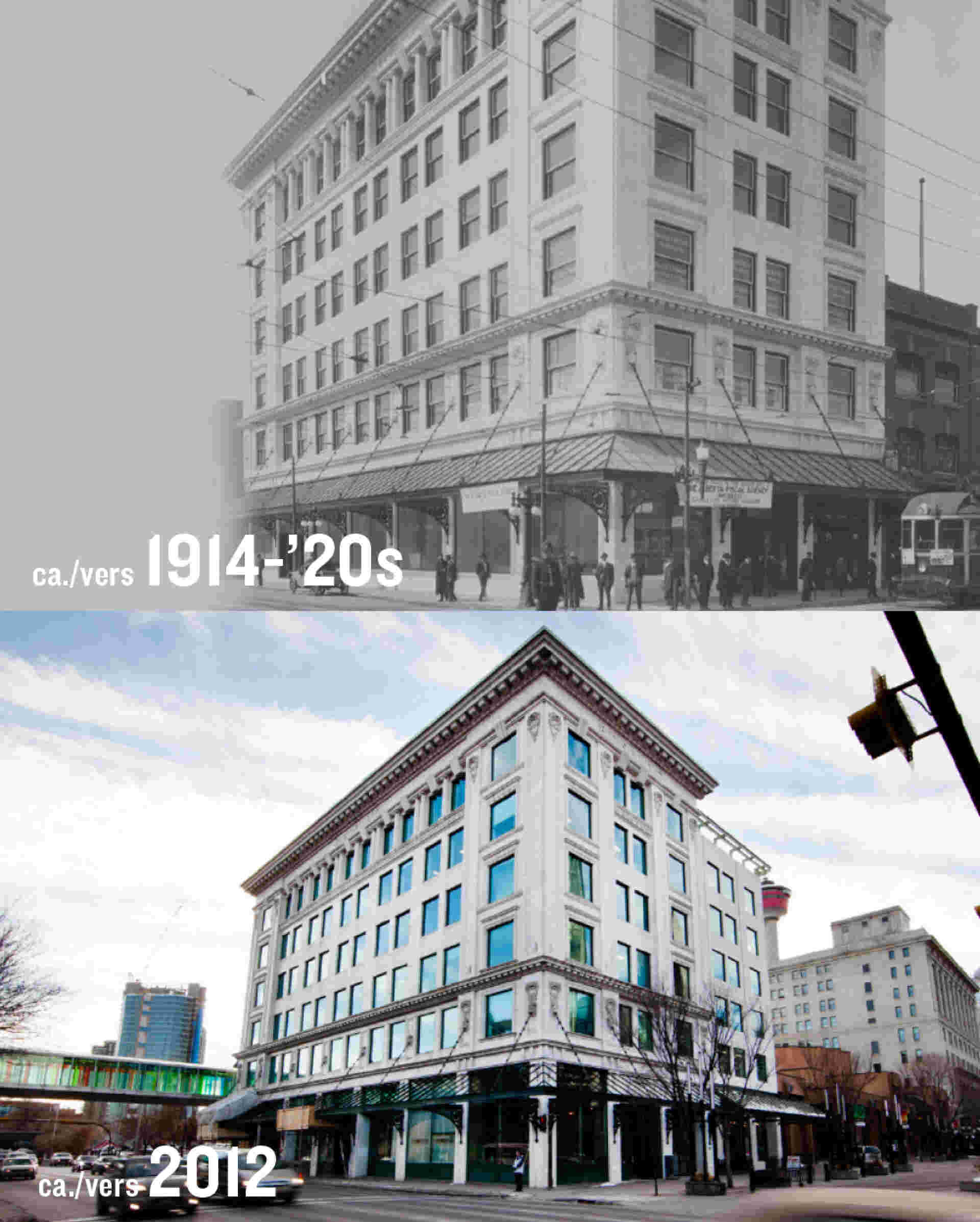

Now & Then How Vancouver’s first skyscraper attained movie-star status.

Fill In The Blank Kellen Hatanaka’s urban infill.

Rethink People in the city always want to move. To a bigger apartment. To a house with a yard. Downtown. Uptown. Or out of the city entirely.

Make room for the arts In an environment designed for cars, in downtown Edmonton, a new mural enlivens the intersection of 104 Street NW and 103 Avenue NW.

The Conversation In an endeavour she calls “food rescue,” Lourdes Juan, an urban planner and the founder of Calgary-based Hive Developments, launched a tech start-up called Knead

Now & Then How Vancouver’s first skyscraper attained movie-star status.

Now & Then Each Allied property is a unique alchemy of forms, uses and stories, accruing value and history over time. For 10 years, Now & Then has been capturing those stories.

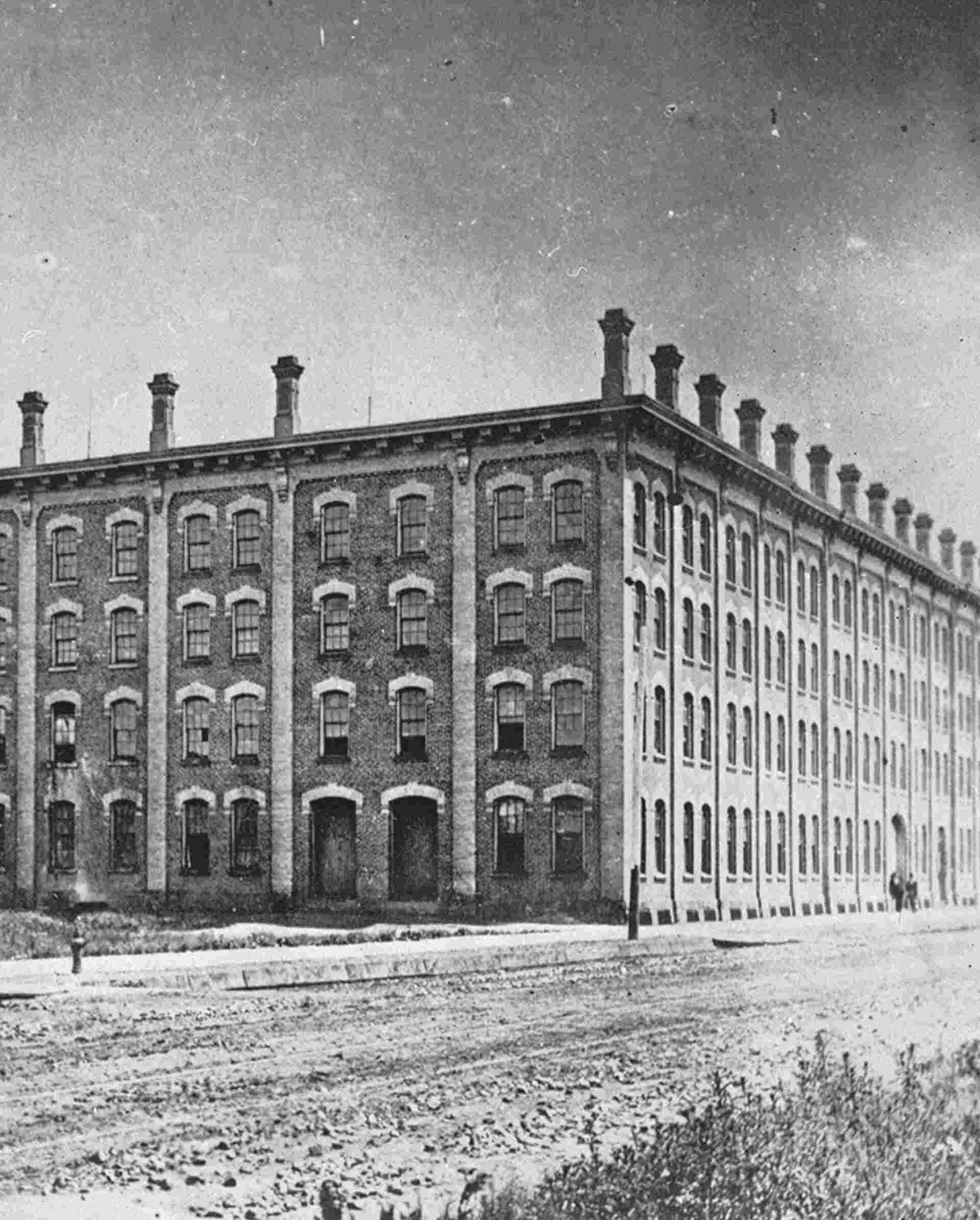

Now & Then The Wilson Building once housed Canada’s first postcard manufacturer

Now & Then Built on beef, Calgary’s historic Burns Building embodies the entrepreneurial spirit that shaped the West.

Digital Edition For the College of Dental Hygienists of Ontario, the journey to Truth and Reconciliation begins with a single step—and is defined by the relationships forged along the way.

Rethink People in the city always want to move. To a bigger apartment. To a house with a yard. Downtown. Uptown. Or out of the city entirely.

The Creator In an urban environment, where foraging isn’t on local activity guides, Jason Logan finds colour.

The Interior Architecture firm Lemay’s Toronto studio intrigues and welcomes.

The Creator Highfield Farm renews the former site of Calgary’s Blackfoot Farmers’ Market.